Benjamin Waugh (20 February 1839 – 11 March 1908) was a Victorian era social reformer and campaigner who founded and directed the UK charity, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) in the late 19th century. He was also a journalist, public speaker and organiser who helped secure Britain’s first legislation on children’s rights.

Benjamin Waugh | |

|---|---|

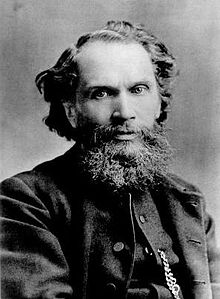

Waugh c. 1900 | |

| Born | 20 February 1839 |

| Died | 11 March 1908 (aged 69) Westcliff, Essex |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Theological college, Bradford |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Religion | Congregationalist |

Early life edit

Waugh was born in Settle, West Riding of Yorkshire. Aged eight, he was affected by the death of his mother and soon afterwards his father sent him to a private school in Warwickshire run by his maternal uncle, a Congregationalist minister. When 14, he was apprenticed to Samuel Boothroyd, a draper and member of the Congregational Church in Southport, Lancashire. By the age of 20, Waugh had become secretary of the local branch of the United Kingdom Alliance, a leading temperance organisation. His religious conviction led to him giving up the drapery business while remaining friendly with his former employer whose daughter Sarah later became his wife. Between 1862 and 1865, he studied at the Congregationalist Airedale Theological College in Bradford and on graduation, married Sarah Boothroyd with whom he moved to Newbury, near Reading, as minister to the local Congregational church. Both politically liberal and a non-fundamentalist, he became a Fellow of the Geological Society in 1865. A year later, he accepted the pastorate of the Independent Chapel at Maze Hill in Greenwich.[1]

Early career edit

As a Congregationalist minister in poverty-stricken East Greenwich, Waugh devoted himself to improving the conditions of the inhabitants, including establishing a creche for working mothers and a Society for Temporary Relief in Poverty and Sickness. In 1870, John Stuart Mill and four trade unions nominated him as a candidate in the election to represent Greenwich on the new London School Board; when elected he argued for non-sectarian elementary education. Befriending fellow Board member Thomas Huxley, he learnt from Huxley the importance of factual investigation during his subsequent campaigns on behalf of neglected children. The first of these concerned the incarceration of child offenders in adult prisons and Waugh became widely known for his book, The Gaol Cradle, Who Rocks it? that pleaded against child imprisonment and for the creation of juvenile courts. The year following its publication he collapsed from over-work but despite thereafter declining re-election to a third three-year term on the School Board, continued to do too much.[2]

The Sunday Magazine edit

After another breakdown in 1877, he resigned his ministry in Greenwich on medical advice and accepted an offer by the publisher Isbister to edit the widely-circulated monthly periodical, the Sunday Magazine.[3] It attracted contributions from numerous well-known writers, including novelist Hesba Stretton who helped found what later was to become the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Waugh also contributed poems and articles to the magazine. His monthly stories 'Sunday Evenings with My Children' were later published in book form.[4]

National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children edit

In 1884, at the suggestion of Hesba Stretton he brought together a number of leading philanthropists to found the London Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (modelled on a similar initiative in Liverpool), launched at London's Mansion House on 8 July. The London body's first chairman was veteran social reformer, Lord Shaftesbury. The Society evolved to become the NSPCC some five years later (14 May 1889), with Waugh as its honorary director and Queen Victoria as patron. Under Waugh's leadership and guidance, 200 local NSPCC branches were created across the UK to campaign for children to be protected from harm, neglect and abuse. Local groups raised funds for the NSPCC, funding a body of inspectors to investigate and prevent cruelty to children. Many of the fund-raisers were middle-class women who, according to social historian George Behlmer, were ‘left no room for doubt on the subject of female duty'. Its women supporters had to postpone fighting for their own rights until ‘the citizenship and rights of children are established’.[2]

Waugh supported the agitation of his friend W. T. Stead against ‘white slavery’ in 1885. He was also instrumental in inserting a provision into the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 allowing law courts to accept as evidence the testimony of children too young to understand the meaning of an oath. Waugh afterwards played leading role in securing the landmark Anti-Cruelty Act 1889, popularly known as the 'Children's Charter', which allowed a child to be taken from abusive parents.[1] Waugh's achievements led to criticism and in 1896 the Echo newspaper accused him of financial mismanagement along with a strong personal attack.

'Mr. Waugh declares that he is above all committees, He initiates expenditure, gives orders, buys houses, starts shelters, takes and dismisses officials without asking permission from committees. The N.S.P.C.C.is virtually a one-man society'.[5]

Lord Herschell's subsequent independent review of the NSPCC management dismissed the slanders, found that the NSPCC had not been financially mismanaged and made some sensible recommendations about tightening up the administration that he concluded was fundamentally sound. And although Herschell found that Benjamin Waugh sometimes used too vehement and impetuous language, "It was rare for the zeal and enthusiasm to promote a great cause... [to be] combined with a philosophic calm".[2]

Waugh was so dedicated to the Society that he refused to take a salary for the first 11 years, relying solely on the income from editing the Sunday Magazine which he eventually gave up in 1895.[1] By early 1904, he was so worn out from over-work that his doctor insisted he take a complete break in the form of a six-month ocean voyage. Although he returned to work in August that year, ill-health compelled him to resign from the NSPCC in March 1905 and he died three years later while visiting Southend-on-Sea, where he is buried in the borough cemetery.

Family and homes edit

With his wife Sarah, Waugh had 11 children (three of whom died in infancy) including his daughters Edna, who would become a notable watercolour artist and Rosa, his biographer and who would follow in his footsteps as a social activist.

When Congregational minister in Greenwich, Waugh lived at Croom's Hill in Greenwich, and at 53 Woodlands Villas (today Vanbrugh Park) in neighbouring Blackheath. In 1879, the family moved to Oak Cottage in Shipbourne, Kent from where they moved in 1881 to 33 The Green, Southgate.[6] In 1888, the family moved to 33 Hatfield Road in St Albans that Waugh named Otterleigh after his mother's birthplace in Yorkshire. In 1902 they settled in Bedford Park, Chiswick until his retirement in 1905 after which he and Sarah moved to Weybridge.

A blue plaque marks the site of the house in Southgate and at what was mistakenly believed to be that of Waugh's residence on Croom's Hill when it was installed in 1984 by the Greater London Council. English Heritage, the successor authority responsible for blue plaques correctly identifies Waugh's former home as 62 Croom's Hill.[7]

Gallery edit

-

Waugh's blue plaque at Croom's Hill, Greenwich

-

The plaque to Benjamin Waugh at 33 The Green.

-

Benjamin Waugh with his wife Sarah and six of his children circa 1883..

References edit

- ^ a b c Waugh, Rosa (1913). The Life of Benjamin Waugh. London: T Fisher Unwin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Behlmer, George K (1982). Child abuse and moral reform in England, 1870-1908. Stanford University Press.

- ^ Behlmer, George K (2004). "Benjamin Waugh". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Waugh, Benjamin (1882). Sunday Evenings with My Children. London: W. Isbister.

- ^ N/A, N/A (5 March 1896). "'The NSPCC: A Study in Philanthropic Finance'". The Echo. p. 1. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ a b "A Walk in Southgate".

- ^ "English Heritage". www.english-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

Sources edit

- Behlmer, George, K. (1982) Child Abuse and Moral Reform in England 1870-1908, Stanford University Press

- Behlmer, George K. "Benjamin Waugh" (2004) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, OUP

- Waugh, Rosa (1913), Life of Benjamin Waugh. T. F Unwin, London.