Benjamin Roberts-Smith VC, MG (born 1 November 1978) is an Australian former soldier[1] who, in a civil defamation trial in 2023 he initiated in the Federal Court of Australia, was found to have committed war crimes (including murder) in Afghanistan during 2009, 2010 and 2012.[2][3][4][5] An appeal to a Full Court of the Federal Court, comprising three judges, commenced on 5 February 2024.[6][7][8]

Ben Roberts-Smith | |

|---|---|

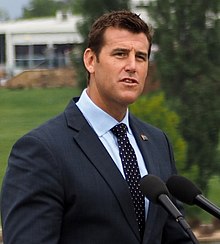

Roberts-Smith in 2015 | |

| Born | 1 November 1978 Perth, Western Australia |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service | Australian Army (1996–2013) Australian Army Reserve (2013–2015) |

| Years of service | 1996–2015 |

| Rank | Corporal |

| Unit | 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1997–2003) Special Air Service Regiment (2003–2013) |

| Battles / wars | International Force East Timor War in Afghanistan Iraq War |

| Awards | Victoria Cross for Australia Medal for Gallantry Commendation for Distinguished Service |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Relations |

|

| Other work | Chairman of the National Australia Day Council (2014–2017) General manager of Seven Queensland (2015–2023) |

Roberts-Smith was awarded a Medal for Gallantry in 2006, the Victoria Cross for Australia in 2011, and a Commendation for Distinguished Service in 2012.[9][10] After discharge from the Australian Army in 2013, he was granted a scholarship to study business at the University of Queensland. In 2015, he was appointed deputy general manager of the regional television network Seven Queensland and later, general manager of Seven Brisbane until temporarily stepping down in 2021 to focus on his defamation action against Nine Entertainment. Following the defamation outcome in 2023, Roberts-Smith resigned from Seven West Media.[11]

In 2017, Roberts-Smith's actions in Afghanistan came under scrutiny in light of an independent war crimes inquiry into "questions of unlawful conduct concerning (Australia's) Special Operations Task Group in Afghanistan".[12] In November 2018, the Australian Federal Police launched an investigation into Roberts-Smith over allegations he committed war crimes in Afghanistan.[13]

With assistance from a legal team hired by Seven Network owner Kerry Stokes, Roberts-Smith commenced defamation proceedings in August 2018 against Nine Entertainment publications The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, and against The Canberra Times, and also named each of the three journalists involved in reporting alleged acts of bullying and war crimes committed by him.[14]

The civil trial commenced in June 2021 in the Federal Court in Sydney.[15] The media outlets mounted a defence which required them to prove the truth of their claims based on the civil standard of proof, on the balance of probabilities, applying the Briginshaw principle.[16] In June 2023, Justice Anthony Besanko dismissed Roberts-Smith's defamation case against the three publications, ruling that it was proven to the standard required in Australian defamation law that Roberts-Smith murdered four Afghans and had broken the rules of military engagement.[16][17][18]

Early life and family

Roberts-Smith was born on 1 November 1978 in Perth, Western Australia. He is the elder son of Sue and Len Roberts-Smith, a former justice of the Supreme Court of Western Australia. He graduated from Hale School in 1995.[19] His brother, Sam, is an opera singer.[20]

Military career

Roberts-Smith joined the Australian Army in 1996 at age eighteen. After completing basic training at Blamey Barracks in Kapooka, he underwent initial employment training at the School of Infantry at Lone Pine Barracks in Singleton; and from there, Roberts-Smith was posted to the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR) in Holsworthy, all in New South Wales. Initially part of a rifle company, he subsequently became a section leader in the Direct Fire Support Weapons Platoon.[21] With 3 RAR, Roberts-Smith was deployed to East Timor twice, the first time as part of the International Force East Timor in 1999.[21]

After completing the Special Air Service Regiment (SASR) selection course in 2003, and the SASR reinforcement cycle, Roberts-Smith was initially posted to 3 Squadron at Campbell Barracks in Perth. He took part in operations off Fiji in 2004, and was part of personal security detachments in Iraq throughout 2005 and 2006. Roberts-Smith was deployed to Afghanistan on six occasions; the first two were in 2006 and 2007. After completing junior leadership training in 2009, he was posted to 2 Squadron as a patrol second-in-command (2IC), and later as a patrol commander. Roberts-Smith was a member of training and assistance teams throughout Southeast Asia. He returned to Afghanistan in 2009, 2010 and 2012.[21]

In 2011, Roberts-Smith noted that he - and the ADF - expected him to be able to continue to fight as a frontline patrol commander following the receipt of the Victoria Cross for Australia. He said that "[O]nce you reach patrol commander, that is the pinnacle for an SAS operator. You are now the man."[22] He left the full-time army in 2013 at age thirty-five with the rank of corporal, and served part-time with the Army Reserve until 2015.

Military decorations

In 2006, Roberts-Smith was awarded the Medal for Gallantry for his operations as a patrol scout and sniper in Afghanistan.[23]

He was presented with the VC by the Governor-General of Australia, Quentin Bryce, at a ceremony held at Campbell Barracks on 23 January 2011.[24][25] The decision to award the VC to Roberts-Smith was raised during defamation proceedings where it was revealed that several former and serving members of the SAS had questioned the decision.[26][27][28]

On 26 January 2014, Roberts-Smith was awarded the Commendation for Distinguished Service as part of the 2014 Australia Day Honours.[29] The award arose from a 2012 tour of Afghanistan, in which Roberts-Smith "distinguished himself as an outstanding junior leader on more than 50 high risk" operations.[30]

A 2014 painting of Roberts-Smith, Pistol Grip by Michael Zavros, hangs in the Australian War Memorial which commissioned it.[31] The National Portrait Gallery commissioned a photo by Julian Kingma of Roberts-Smith in 2018.[32] The uniform he wore in Afghanistan is also displayed in the War Memorial.[33] In 2023, Kim Beazley, Chair of the Australian War Memorial Council, acknowledged "the gravity of the decision in the Ben Roberts-Smith VC MG defamation case and its broader impact on all involved in the Australian community".[34] Careful consideration is being given to the additional content and context to be included in collection items on display.[34]

In June 2024, Roberts-Smith attended Government House, Western Australia to receive the King Charles III Coronation Medal, bestowed by King Charles III on all living Australian recipients of the Victoria Cross.[35] Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese commented that the decision to include Roberts-Smith had been made by the Palace and not the Australian government.[36]

| Ribbon | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Victoria Cross for Australia | ||

| Medal for Gallantry | ||

| Commendation for Distinguished Service | ||

| Australian Active Service Medal | with clasps for EAST TIMOR, ICAT and IRAQ 2003 | |

| International Force East Timor Medal | ||

| Afghanistan Medal | ||

| Iraq Medal | ||

| Australian Service Medal | with clasps for CT/SR (Counter Terrorism / Special Recovery) | |

| Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal | ||

| Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Medal | ||

| King Charles III Coronation Medal | ||

| Defence Long Service Medal | ||

| Australian Defence Medal | ||

| United Nations Medal | ||

| NATO Medal for the Non-Article 5 ISAF Operation in Afghanistan | with ISAF clasp | |

| Unit Citation for Gallantry | with Federation Star | |

| Meritorious Unit Citation | ||

| Infantry Combat Badge |

Corporate career

In October 2013, when Roberts-Smith announced that he was leaving the Army,[37] the University of Queensland offered him a scholarship to study a Master of Business Administration, with a view to establishing a program to support other soldiers in transitioning to a corporate career. Roberts-Smith graduated in December 2016 at age 38 and said "I joined the army at 18 so I hadn't gone to university for a Bachelor degree and I didn't have the base level of business knowledge because there were many things I just hadn't been exposed to."[38][39][40] Nevertheless, he was appointed deputy general manager of regional television network Seven Queensland in April 2015, and two months later promoted to general manager.[41][42] In April 2016, Roberts-Smith was also made general manager of Seven Brisbane following the resignation of Max Walters.[43][44]

While at Seven Queensland, Roberts-Smith was recorded expressing disdain for the media business, dislike of fellow Seven executives and incredulity that he was still running Seven Queensland despite being at the centre of a war crimes scandal. He also felt indebted to media mogul and Seven owner Kerry Stokes for financing his personal legal actions.[45] It was alleged in February 2022 during defamation proceedings that Roberts-Smith had employed a private investigator, John McLeod, to pose as a barman during a Seven Queensland work event in order to listen to staffers at the event and discern their opinions on Roberts-Smith.[46]

In April 2021, Roberts-Smith temporarily stepped down from Seven Queensland to focus on his defamation action against Nine Entertainment.[47] In June 2023, he resigned from Seven following the case's unsuccessful outcome.[48]

Other activities

From 2014 to 2017, Roberts-Smith was chair of the National Australia Day Council, an Australian Government-owned social enterprise.[49] Separately in 2015, the voices of Roberts-Smith and various others were featured in the song Lest We Forget with Australian country music singer Lee Kernaghan on the studio album Spirit of the Anzacs.[50]

War crime allegations

In October 2017, actions involving Roberts-Smith came under further scrutiny. One controversy concerned the killing of a person, who Roberts-Smith had claimed was a Taliban spotter, during a confrontation in May 2006 at Chora Pass. According to the journalist Chris Masters, two members of the patrol had witnessed a lone Afghan teenager approaching the patrol observation post, leaving shortly thereafter. Although the two operators had decided it was not necessary to engage the Afghan, Roberts-Smith and patrol 2IC Matthew Locke arrived on-scene and the pair "decided to hunt down and shoot dead the two 'enemy' after concluding they had spotted the patrol".[51]

The patrol report had identified only a single Afghan unarmed "spotter", but Roberts-Smith later said that two armed insurgents had approached the position in an oral account provided to the Australian War Memorial. When the inconsistency was raised, Roberts-Smith claimed to have remembered incorrectly.[52]

Following the publication of Masters' book No Front Line in October 2017, Fairfax Media's Nick McKenzie and the ABC's Dan Oakes covered the story, linking the case to an ongoing inquiry by the Inspector-General of the ADF into criminal misconduct on the battlefield by special forces; an inquiry that resulted in the Brereton Report. Responding to the coverage in an interview with The Australian, Roberts-Smith described the scrutiny as "un-Australian". Oakes wrote "It's not 'un-Australian' to investigate the actions of special forces in Afghanistan".[53]

In June 2018, a joint ABC–Fairfax investigation detailed an assault on the village of Darwan in September 2012 during which a handcuffed man was kicked off a cliff by an Australian special forces soldier nicknamed "Leonidas" after the famed Spartan king.[54][55][56] On 6 July 2018, Fairfax Media reported that Roberts-Smith was "one of a small number of soldiers subject to investigation by an inquiry looking into the actions of Australian special forces soldiers in Afghanistan".[57] In August 2018, Fairfax Media reported that Roberts-Smith bullied several of his fellow soldiers as well as a female companion's allegations that she was subjected to an act of domestic violence in Australia. Roberts-Smith denied these allegations.[58]

In June 2023, ABC reported that it has been alleged that Roberts-Smith directed another SASR soldier to kill an elderly imam during an August 2012 operation in Afghanistan. It has been alleged that this led to the man being dragged from a mosque and killed, despite him being unarmed and a prisoner of the Australians. This incident was among those which the Brereton Report recommended be considered by war crimes investigators.[59]

Investigation

In November 2018, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) announced that they "received a referral to investigate allegations of war crimes committed by Australian soldiers during the Afghanistan conflict".[13] The Federal Court of Australia declared in September 2020 that no charges against Roberts-Smith had been laid.[60] In April 2021, the AFP confirmed it was also conducting a probe into allegations that Roberts-Smith had destroyed or buried evidence directly related to the ongoing investigation.[61] The Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions later decided that the original AFP investigation could not lead to a prosecution, because of the likelihood that information it had received from the Brereton inquiry would be inadmissible, due to the Inspector-General's use of special coercive powers to question serving members of the ADF.[62] The abandonment of the probe led to the establishment of a new joint taskforce with personnel from the Office of the Special Investigator and a new team of federal police investigators to investigate the allegations.[62]

Defamation suit

In response to this series of articles, in January 2019 Roberts-Smith commenced defamation proceedings in the Federal Court against Fairfax Media (a subsidiary of Nine Entertainment) and two journalists, Nick McKenzie and Chris Masters, and a former journalist, David Wroe. In its truth defence, Fairfax defended its reporting as "substantially true", detailing a series of six unlawful killings alleged to have been carried out by Roberts-Smith in Afghanistan, including those in Darwan.[63]

Kerry Stokes' private investment company Australian Capital Equity (ACE) extended Roberts-Smith a line of credit, against which he drew $1.9 million.[64] Stokes and another director of ACE are also on the board of the Australian War Memorial (AWM). Calls were made at the time for Stokes, as then AWM chairman, to stand down over his public and private support for soldiers accused of war crimes in Afghanistan.[65]

In August 2020, it was reported that legal experts had raised concerns about a personal relationship between Roberts-Smith and his defamation lawyer, saying it could constitute unprofessional conduct.[66] News Corp Australia published a photo of Roberts-Smith holding hands with the lawyer, who they reported was visiting him in his new apartment in Brisbane.[64] The lawyer conceded that it was "unwise to spend time with him socially".[67]

In the Federal Court, the Fairfax/Nine Entertainment lawyer Sandy Dawson claimed that Roberts-Smith and his wife had given inconsistent accounts about the status of their relationship during previous years.[68]

On 1 September 2020, Dawson told the Federal Court that the Australian Federal Police had information, including an eyewitness, that allegedly implicated Roberts-Smith in Afghanistan war crimes.[69] The defamation trial, expected to last for ten weeks, commenced in June 2021 in Sydney.[15]

The Federal Court established an online file in view of the public interest where documents were placed when considered publicly accessible.[70]

In April 2021, The Age published an article alleging that Roberts-Smith had attempted to cover up the alleged crimes by hiding incriminating images on a USB drive buried in his back yard, which has since been obtained by the Australian Federal Police.[71]

A colleague of Roberts-Smith, referred to as Person 16 (identity legally protected as part of proceedings), told the court in 2022 that Roberts-Smith had shot dead an unarmed Afghan teenage prisoner in 2012, and bragged about it.[72][73]

Several serving members of the SASR spoke during Roberts-Smith's defamation trial regarding bullying and threats made by Roberts-Smith during his service both within Australia and Afghanistan. "Person 1", a serving SASR member, conveyed that Roberts-Smith had stated to him he would "put a bullet in the back of his head" if he didn't improve his performance. Following this, Person 1 was advised by other members to report Roberts-Smith's threat which he did, leading to Roberts-Smith threatening him again, stating "If you’re going to make accusations, cunt, you’d better have some fucking proof." Reports of Roberts-Smith's bullying were also reiterated by Person 43 and Person 10, other serving members of the SASR.[74][75]

Fairfax Media’s defence against Roberts-Smith’s suit ended in early April 2022 after calling witnesses for eleven weeks.[76]

Judgment

On 1 June 2023, Justice Anthony Besanko dismissed the defamation case brought by Roberts-Smith. Besanko found that the newspapers on trial, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and The Canberra Times, had established substantial or contextual truth of many of their allegations, including that Roberts-Smith "broke the moral and legal rules of military engagement and is therefore a criminal”.[77][78] As a defamation suit is a civil proceeding, Besanko was required by the Evidence Act to assess the evidence using the civil standard of proof, the balance of probabilities, instead of the criminal standard of proof, beyond reasonable doubt.[77][79][80] Due to the gravity of the allegations,[81] Besanko followed the Briginshaw principle which required stronger evidence than would be necessary for a less serious matter.[16][82][83]

Besanko found that four murder allegations against Roberts-Smith had been proven.[18][84] Besanko found that it was substantially true that:

- during the Whiskey 108 mission in 2009 Roberts-Smith committed murder "by machine gunning a man with a prosthetic leg"; Roberts-Smith later asked other soldiers to drink from the prosthetic leg.[17][85][86]

- during the same Whiskey 108 mission Roberts-Smith committed murder "by pressuring a newly deployed and inexperienced SASR soldier to execute an elderly, unarmed Afghan in order to 'blood the rookie'";[17][85][86] and

- during the Darwan mission in September 2012, Roberts-Smith "murdered an unarmed and defenceless Afghan civilian, by kicking him off a cliff and procuring the soldiers under his command to shoot him";[17][85][86]

- during the Chinartu mission in October 2012, Roberts-Smith gave the order to another soldier "to shoot an Afghan male who was under detention"; with instructions being given "to an NDS-Wakunish soldier who then shot the Afghan male in circumstances amounting to murder", rendering Roberts-Smith "complicit in and responsible for murder".[87][88]

It was also ruled that two allegations of murder at Syahchow and Fasil in 2012 were not proven.[17][78]

Besanko separately found that it was proven that:

- in 2010 Roberts-Smith physically attacked an unarmed Afghan man until two patrol commanders ordered him to stop;[89]

- in 2012, Roberts-Smith assaulted a second unarmed Afghan man and authorised the assault of a third unarmed Afghan man who was being held in custody and did not pose a threat;[89] and

- Roberts-Smith engaged in a "campaign of bullying" and threatened violence against an Australian soldier.[17][89]

Meanwhile, it was ruled that allegations that Roberts-Smith committed domestic violence and threatened to report another soldier to the International Criminal Court had not been proven, but did not further harm Roberts-Smith’s reputation given the other substantially true allegations, thus establishing contextual truth.[78]

Judge Besanko also stated that Roberts-Smith was not a reliable witness due to having an obvious motive to lie. Besanko also stated that he believed that Roberts-Smith had threatened a soldier who gave testimony against him.[90]

On 15 June 2023, Roberts-Smith stated that he was proud of his actions in Afghanistan and would not be apologising.[91] Later in June, he accepted liability for payment of the legal costs of his failed defamation suit against the three newspapers from 17 March 2020.[92][6] One respondent to the case previously stated that approximately $30 million was spent on successfully defending it.[92] In November 2023, it was ruled that Roberts-Smith should pay approximately ninety-five percent of the costs incurred by Nine Entertainment from when he began proceedings against them in 2018.[93] The following month, it was reported that Kerry Stokes (Roberts-Smith's former employer and financial backer) would pay most of these costs to his commercial rival, Nine.[94][95]

Appeal

On 11 July 2023, Roberts-Smith filed an appeal against Justice Besanko's judgment to the Full Court of the Federal Court after being granted an extension.[6][7] Nine Entertainment said it would oppose the appeal.[6] In October, the Court ordered Roberts-Smith to pay almost $1 million in security for costs ahead of an appeal.[96][97]

Further controversy

In September 2024 it was reported that Roberts-Smith had attended a recent Australian Defence Force gala dinner to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of the Special Air Service Regiment and that some who had served in the special forces found this inappropriate. The same report said that the Office of the Special Investigator could soon bring criminal charges against Roberts-Smith, including further alleged war crimes and other criminal matters.[98]

Personal life

Roberts-Smith met Emma Groom in 1998 at Holsworthy Barracks, Sydney. She came from a military family. On 6 December 2003, the couple married at the University of Western Australia.[99] Their twin daughters were born in 2010. Roberts-Smith was named 2013 Australian Father of the Year by The Shepherd Centre, a not-for-profit charitable organisation.[100] On retirement from the army in 2015, he moved to Queensland with his wife and daughters.[101] In December 2020, their divorce was finalised.[102][103][104]

In 2017–2018, Roberts-Smith allegedly had a six-month affair with an unnamed woman given the pseudonym "Person 17" in the defamation trial that he initiated. When Person 17 became pregnant, Roberts-Smith allegedly hired a private investigator to monitor Person 17 and confirm her attendance at an abortion clinic. Person 17 accused Roberts-Smith of punching her in the face after a dinner at Parliament House in 2018. Roberts-Smith denies ever striking her.[105] Person 17 also accused Roberts-Smith of coaching her on how to explain a black eye resulting from the alleged assault.[106]

In January 2022, Roberts-Smith was ordered to pay the legal costs of his ex-wife after unsuccessfully trying to sue her in the Federal Court over allegations that she accessed confidential emails.[107]

References

- ^ "Australian soldier Ben Roberts-Smith 'complicit in murder': Judge". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Alexander, Michaela Whitbourn, Harriet (1 June 2023). "Former SAS soldier committed war crimes". The Age. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benns, Matthew; Tonkin, Shannon (1 July 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith defamation trial: Murderer, war criminal: Judge throws out BRS defamation case". The Advertiser. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Middleton, Karen (10 June 2023). "Exclusive: More soldiers willing to testify against Ben Roberts-Smith". The Saturday Paper. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Housden, Tom; Turnbull, Tiffanie (2 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith case: Will Australia see a war crimes reckoning?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d McKinnell, Jamie (11 July 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith to appeal after losing landmark defamation case". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ a b Pelly, Michael (14 July 2023). "Now it's Ben Roberts-Smith v Justice Anthony Besanko". Australian Financial Review. Nine Entertainment. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Whitbourn, Michaela (5 February 2024). "Roberts-Smith fronts court as million-dollar defamation appeal starts". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Dodd, Mark (21 January 2010). "Second SAS Afghan Victoria Cross for heroic charge". The Australian. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Parkes-Hupton, Heath (2 June 2023). "From 'Australian hero' to 'disgracing' his country — Ben Roberts-Smith's fall from grace". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Meade, Amanda (2 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith resigns from Seven after losing defamation fight against Nine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force Afghanistan Inquiry Report (PDF). Australia: Department of Defence. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ a b McKenzie, Nick; Masters, Chris (28 November 2018). "Police investigate Ben Roberts-Smith over alleged war crimes". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Simone Fox Koob (17 August 2018). "Ben Roberts-Smith files defamation proceedings against Fairfax". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b Jamie McKinnell (10 June 2021). "Tearful Ben Roberts-Smith breaks down in court after being grilled over alleged murders". ABC News (Australia). Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Whitbourn, Michaela (25 May 2023). "'The stakes are incredibly high': Judge to rule on Roberts-Smith case". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Whitbourn, Michaela; Alexander, Harriet (1 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith case: Former SAS soldier committed war crimes". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ a b Yong, Nicholas (5 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith threatened witnesses in defamation trial, judge says". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ Phillips, Yasmine (4 February 2011). "VC hero Ben Roberts-Smith urges students to strive for excellence". PerthNow. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Tanya MacNaughton (18 October 2016). "Baritone Sam Roberts-Smith gets hooked on WA Opera's The Pearl Fishers". PerthNow. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Australian Army Awarded the Victoria Cross for Australia/Medal for Gallantry Corporal Benjamin Roberts-Smith, VC, MG – Citation". Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via Trove.

- ^ Nicholson, Brendan (24 January 2011). "Professional soldier just wants to get back to work". The Australian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "Medal for Gallantry: Lance Corporal Ben Roberts-Smith, Special Air Service Regiment, Australian Army". www.awm.gov.au. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Victoria Cross for Australia (VC) – Corporal Benjamin Roberts-Smith MG, WA", Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, no. S 12, 24 January 2011

- ^ AAP (23 January 2010). "SAS digger awarded VC for taking on Taliban". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ "Soldiers believe events that earned Ben Roberts-Smith Victoria Cross may have been 'falsified', court hears". ABC News. 3 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "SAS soldiers considered Ben Roberts-Smith 'arrogant' and undeserving of Victoria Cross, court told". The Guardian. 3 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Whitbourn, Michaela (8 February 2022). "Soldier harboured doubts about Roberts-Smith's VC honour, court told". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Commendation for Distinguished Service" (PDF). Website of the Governor General of Australia. Australian Honours and Awards Secretariat. 26 January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Awarded the Commendation for Distinguished Service: Corporal Benjamin Roberts-Smith, VC, MG – Citation" (PDF). Australian Army. 26 January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "Pistol Grip (Ben Roberts-Smith VC)" Archived 27 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Australian War Memorial

- ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith, 2018, by Julian Kingma" Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, National Portrait Gallery (Australia)

- ^ Yan Zhuang (3 October 2021). "He's Australia's Most Decorated Soldier. Did He Also Kill Helpless Afghans?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Statement from Australian War Memorial Chair, the Hon Kim Beazley AC, on behalf of Australian War Memorial Council | Australian War Memorial". Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ McKenzie, Nick; Burton, Jesinta; Thompson, Holly (29 June 2024). "WA governor hosts Ben Roberts-Smith receives medal from the King". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Kelly, Cait (29 June 2024). "Decision to award Ben Roberts-Smith extra medal made by King Charles, not Australia, Albanese says". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Victoria Cross recipient Ben Roberts-Smith leaving Army for career in business". ABC News. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "War hero credits MBA for transition from battlefield to corporate suite". UQ News. 9 December 2016. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Nicholson, Brendon. "VC hero Ben Roberts-Smith swaps battlefield for boardroom". The Australian. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Nicholson, Brendan. "Lessons from another battlefront for Ben Roberts-Smith". The Australian. News Corp. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith appointed deputy general manager of 7 Queensland". news.com.au. 23 April 2015. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Seven West Media promotes VC recipient Ben Roberts-Smith to GM Queensland office". mUmBRELLA. 2 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ Knox, David (12 April 2016). "Ben Roberts-Smith appointed General Manager, Seven Brisbane". TV Tonight Newsletter. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Bennett, Stephanie (8 March 2016). "Channel 7 boss Max Walters quits after 26 years with the network". PerthNow. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Masters, Nick McKenzie, Joel Tozer, Chris (11 April 2021). "'I'm going to do everything I can to f---ing destroy them': Secret Ben Roberts-Smith audio revealed". The Age. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith tried to cover up writing threatening letters to SAS soldier, court hears". The Guardian. 23 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Kruimel, Olivia (26 April 2021). "Seven's Ben Roberts-Smith takes leave of absence for defamation case". Mumbrella. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Buckingham-Jones, Sam (2 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith resigns from Seven". Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "National Australia Day Council". National Australia Day Council. 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ McCabe, Kathy (15 March 2015). "Letters to families from the frontlines of war are given a voice on Spirit Of The Anzacs album". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ McKenzie, Nick (19 October 2017). "The fog of war and politics leads to controversy over Afghan war mission". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Masters, Chris (2017). No Front Line: Australia's Special Forces at War in Afghanistan. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781760111144.

- ^ Oakes, Dan (26 October 2017). "It's not 'un-Australian' to investigate the actions of special forces in Afghanistan". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ McKenzie, Nick (8 June 2018). "SAS soldier accused of killing innocent villager". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Dan Oakes (10 June 2018). "Death in Darwan". ABC News. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Maley, Paul (27 September 2019). "Ben Roberts-Smith and the battle on the home front". The Australian. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ McKenzie, Nick; Masters, Chris (6 July 2018). "VC winner Ben Roberts-Smith among subjects of defence investigation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ McKenzie, Nick; Wroe, David; Masters, Chris (10 August 2018). "Beneath the bravery of our most decorated soldier". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Willacy, Mark; Robertson, Josh; Callinan, Rory (8 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith revealed as soldier accused in Brereton inquiry of directing killing of imam". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications FCA 1285 Archived 27 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Craig Grierson Colvin J, Federal Court of Australia, 8 September 2020

- ^ McKenzie, Nick; Masters, Chris; Tozer, Joel (12 April 2021). "Ben Roberts-Smith under fresh investigation over burner phones and sealed envelopes". The Age. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ a b "No apologies as Roberts-Smith returns to Australia following defamation judgment". The Age. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Whitbourn, Michaela (19 October 2018). "Fairfax defends Ben Roberts-Smith defamation claim". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b Aston, Joe (15 November 2020). "Ben Roberts-Smith owes Kerry Stokes $1.9m". Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Galloway, Anthony (25 November 2020). "'Discredited': Former War Memorial historian calls for Kerry Stokes to stand down". The Age. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Galloway, Anthony (8 August 2020). "Legal experts raise concern about Ben Roberts-Smith's personal relationship with lawyer". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Whinnett and Smith, Ellen and Zoe (10 August 2020). "Ben Roberts-Smith: war hero's lawyer admits personal relationship 'unwise'". The Courier Mail. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Cooper, Adam (2 November 2020). "Ben Roberts-Smith asked wife to lie about his affair, court told". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Knaus, Christopher (1 September 2020). "Australian police told Ben Roberts-Smith they had witnesses to alleged Afghanistan war crimes, court hears". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith". Federal Court of Australia. 11 September 2020. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Buried evidence and threats: How Ben Roberts-Smith tried to cover up his alleged crimes". The Age. 11 April 2021. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith described alleged execution of Afghan teen as 'beautiful thing', court hears". ABC. 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Doherty, Ben (11 February 2022). "Ben Roberts-Smith called alleged killing of unarmed Afghan teenager 'beautiful thing', court hears". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 29 April 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith was a 'bully' and prestigious award was an error, fellow soldier tells court". ABC News. 11 March 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith warned soldier he would get 'bullet in the back of the head', court told". the Guardian. 17 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "First witness called by Ben Roberts-Smith's lawyers denies ordering prisoner's death to 'blood rookie'". ABC News. 19 April 2022. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b Doherty, Ben (1 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith loses defamation case with judge saying newspapers established truth of murders". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Visontay, Elias; Doherty, Ben (1 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith: the murders and war crimes at the heart of a seismic defamation battle". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (No 41) [2023] FCA 555". Austlii. 1 June 2023. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Bachelard, Michael (1 June 2023). "What it took to win the biggest defamation case in Australia's history". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (No 41) [2023] FCA 555". www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au. Archived from the original on 15 June 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

paragraphs [113] - [114]

- ^ Hannaford, Patrick (1 June 2023). "Leading media lawyer Justin Quill says 'the big winners' in the Ben Roberts-Smith defamation case will be the lawyers". Sky News Australia. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Pelly, Michael (1 June 2023). "Tables turned on Ben Roberts-Smith – and Kerry Stokes". Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ Doherty, Ben (6 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith judgment shows few have ever fallen so far". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b c McKinnell, Jamie (1 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith loses mammoth defamation battle against newspapers, reporters". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Ben Roberts-Smith defamation judgment: read Justice Anthony Besanko's full summary". The Guardian. 1 June 2023. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Kaye, Byron (5 June 2023). "Australia's most decorated war veteran "responsible for murder", says judge". Reuters. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "An 'unreliable witness' with 'motives to lie': Judge's assessment of Ben Roberts-Smith". SBS News. Australian Associated Press. 5 June 2023. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Wootton, Hannah (1 June 2023). "What the judge decided in the Ben Roberts-Smith case". Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Michaela, Whitbourn (5 June 2023). "'Not an honest and reliable witness': Judge's scathing assessment of Roberts-Smith". The Age. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah (15 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith: Top soldier won't apologise for alleged war crimes". BBC. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ a b McKinnell, Jamie (29 June 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith agrees to pay defamation case legal costs, which could run into tens of millions". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Mason, Max (28 November 2023). "Roberts-Smith to pay 95pc of Nine's costs in defamation mega-trial". Financial Review. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Kerry Stokes to pay Nine's court costs over Ben Roberts-Smith defamation trial". ABC News. 11 December 2023. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "Billionaire's bill for Ben Roberts-Smith's failed defamation suit". www.9news.com.au. 11 December 2023. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ McKinnell, Jamie (10 October 2023). "Ben Roberts-Smith ordered to pay $910k before appeal over war crimes defamation decision". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ These incidents are covered in the documentary film Revealed: Ben Roberts-Smith - Truth On Trial.

- ^ McKenzie, Nick; Knott, Matthew (13 September 2024). "Ben Roberts-Smith welcomed at Defence party days before Marles strips officers' medals". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Federal Court of Australia Affidavit" (PDF). Page 104 of affidavit. 19 October 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Landy, Samantha. "Victoria Cross hero Ben Roberts-Smith named Father of the Year". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Gould, Joel (Winter 2017). "When the war is over". The University of Queensland. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Rolfe, Brooke (9 June 2021). "Inside Ben Roberts-Smith's new relationship". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Scheikowski, Margaret (2 November 2020). "Deeply personal Roberts-Smith info sought". The Times. Victor Harbour, South Australia. Australian Associated Press. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Parkes-Hupton, Heath (2 November 2020). "Ben Roberts-Smith: Newspapers seek 'deeply personal' docs about SAS hero's alleged affair". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "A prosthetic leg, an affair and burnt laptops: Ben Roberts-Smith case hears extraordinary evidence". The Guardian. 25 June 2021. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Cooper, Adam (22 November 2018). "Woman says war hero Ben Roberts-Smith told her how to explain black eye". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Ben Roberts-Smith loses case against ex-wife, court orders he pay costs". ABC News. 21 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

External links

- Media related to Ben Roberts-Smith at Wikimedia Commons

- Pedersen, Peter (January 2012). "The falling leaves of Tizak". Wartime Magazine. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

In this interview, he speaks at length publicly for the first time about the circumstances that led to the award.

- Besanko, Anthony James (1 June 2023). "Reasons for Judgment - Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (No 41) [2023] FCA 555". Federal Court of Australia. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023.