This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

In anatomy, the atlas (C1) is the most superior (first) cervical vertebra of the spine and is located in the neck.

| Atlas (anatomy) | |

|---|---|

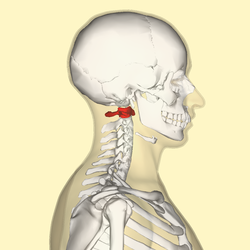

Position of the atlas shown in red | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | atlas, vertebra cervicalis I |

| MeSH | D001270 |

| TA98 | A02.2.02.101 |

| TA2 | 1038 |

| FMA | 12519 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The bone is named for Atlas of Greek mythology, for just as Atlas bore the weight of the heavens, the first cervical vertebra supports the head.[1] However, the term atlas was first used by the ancient Romans for the seventh cervical vertebra (C7) due to its suitability for supporting burdens.[2] In Greek mythology, Atlas was condemned to bear the weight of the heavens as punishment for rebelling against Zeus. Ancient depictions of Atlas show the globe of the heavens resting at the base of his neck, on C7. Sometime around 1522, anatomists decided to call the first cervical vertebra the atlas.[2] Scholars believe that by switching the designation atlas from the seventh to the first cervical vertebra Renaissance anatomists were commenting that the point of man’s burden had shifted from his shoulders to his head--that man’s true burden was not a physical load, but rather, his mind.[2]

The atlas is the topmost vertebra and the axis (the vertebra below it) forms the joint connecting the skull and spine. The atlas and axis are specialized to allow a greater range of motion than normal vertebrae. They are responsible for the nodding and rotation movements of the head.

The atlanto-occipital joint allows the head to nod up and down on the vertebral column. The dens acts as a pivot that allows the atlas and attached head to rotate on the axis, side to side.

The atlas's chief peculiarity is that it has no body,[3] which has fused with the next vertebra.[4] It is ring-like and consists of an anterior and a posterior arch and two lateral masses.

The atlas and axis are important neurologically because the brainstem extends down to the axis.

Structure edit

Anterior arch edit

The anterior arch forms about one-fifth of the ring: its anterior surface is convex, and presents at its center the anterior tubercle for the attachment of the Longus colli muscles and the anterior longitudinal ligament; posteriorly it is concave, and marked by a smooth, oval or circular facet (fovea dentis), for articulation with the odontoid process (dens) of the axis.

The upper and lower borders respectively give attachment to the anterior atlantooccipital membrane and the anterior atlantoaxial ligament; the former connects it with the occipital bone above, and the latter with the axis below.[5]

Posterior arch edit

The posterior arch forms about two-fifths of the circumference of the ring: it ends behind in the posterior tubercle, which is the rudiment of a spinous process and gives origin to the Recti capitis posteriores minores and the ligamentum nuchae. The diminutive size of this process prevents any interference with the movements between the atlas and the skull.

The posterior part of the arch presents above and behind a rounded edge for the attachment of the posterior atlantooccipital membrane, while immediately behind each superior articular process is the superior vertebral notch (sulcus arteriae vertebralis). This is a groove that is sometimes converted into a foramen by ossification of the posterior atlantooccipital membrane to create a delicate bony spiculum which arches backward from the posterior end of the superior articular process. This anatomical variant is known as an arcuate foramen.

This groove transmits the vertebral artery, which, after ascending through the foramen in the transverse process, winds around the lateral mass in a direction backward and medially to enter the vertebrobasilar circulation through the foramen magnum; it also transmits the suboccipital nerve (first spinal nerve)

On the under surface of the posterior arch, behind the inferior articular facets, are two shallow grooves, the inferior vertebral notches. The lower border gives attachment to the posterior atlantoaxial ligament, which connects it with the axis.

Lateral masses edit

The lateral masses are the most bulky and solid parts of the atlas, in order to support the weight of the head.

Each carries two articular facets, a superior and an inferior.

- The superior facets are of large size, oval, concave, and approach each other in front, but diverge behind: they are directed upward, medially, and a little backward, each forming a cup for the corresponding condyle of the occipital bone, and are admirably adapted to the nodding movements of the head. Not infrequently they are partially subdivided by indentations which encroach upon their margins.

- The inferior articular facets are circular in form, flattened or slightly convex and directed downward and medially, articulating with the axis, and permitting the rotatory movements of the head.

Vertebral foramen edit

Just below the medial margin of each superior facet is a small tubercle, for the attachment of the transverse atlantal ligament which stretches across the ring of the atlas and divides the vertebral foramen into two unequal parts:

- the anterior or smaller receiving the odontoid process of the axis

- the posterior transmitting the spinal cord (medulla spinalis) and its membranes

This part of the vertebral canal is of considerable size, much greater than is required for the accommodation of the spinal cord.

Transverse processes edit

The transverse processes are large; they project laterally and downward from the lateral masses, and serve for the attachment of muscles which assist in rotating the head. They are long, and their anterior and posterior tubercles are fused into one mass; the foramen transversarium is directed from below, upward and backward.

Development edit

The atlas is usually ossified from three centers.[6]

Of these, one appears in each lateral mass about the seventh week of fetal life, and extends backward; at birth, these portions of bone are separated from one another behind by a narrow interval filled with cartilage.

Between the third and fourth years they unite either directly or through the medium of a separate center developed in the cartilage.

At birth, the anterior arch consists of cartilage; in this a separate center appears about the end of the first year after birth, and joins the lateral masses from the sixth to the eighth year.

The lines of union extend across the anterior portions of the superior articular facets.

Occasionally there is no separate center, the anterior arch being formed by the forward extension and ultimate junction of the two lateral masses; sometimes this arch is ossified from two centers, one on either side of the middle line.

Variations edit

Accessory transverse foramen of the atlas is present in 1.4–12.5% across the population.[7]

Foramen arcuale or a bony bridge above the vertebral artery on the posterior arch of the atlas may be present. This foramen has an overall prevalence of 9.1%.[8] Arch defects refer to the condition where a gap or cleft exists at the anterior arch or posterior arch of the atlas. The prevalence of the posterior arch defect and anterior arch defect was 0.95% and 0.087%, respectively.[9] The anterior arch defect may be presented along with posterior arch defect, a condition known as combined arch defect or bipartite atlas.[10]

Function edit

Muscular attachments edit

Transverse processes edit

Upper surface:

- rectus capitis anterior – occipital bone (inferior surface of the base)

- rectus capitis lateralis – occipital bone (beneath the jugular process)

- obliquus capitis superior – occipital bone (between the superior and inferior nuchal lines)

Interior and dorsal part:

- obliquus capitis inferior – spinous process of the axis

Lower surface:

- splenius cervicis (part) – spinous processes of T02–T05

- levator scapulae (part) – superior part of medial border of the scapula

- intertransversarius posterior cervicis – transverse process of the axis (posterior tubercle)

- intertransversarius anterior cervicis – transverse process of the axis (anterior tubercle)

Posterior tubercle edit

Upper surface:

- rectus capitis posterior minor – occipital bone (medial part of the interior nuchal line, and the surface between it and the foramen magnum)

Lower surface:

- interspinalis cervicis – spinous process of the axis

Anterior arch edit

- longus colli (superior oblique) – transverse processes of C03–C05.

Clinical significance edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2014) |

There are 5 types of C1 fractures referred to as the Levine Classification of Atlas Fractures

Type 1: Isolated bony apophysis (transverse process fracture

Type 2: Isolated posterior arch fractures

Type 3: Isolated anterior arch fracture

Type 4: Comminuted fracture of the lateral mass

Type 5: Bilateral burst fracture (AKA Jefferson Fracture)

A break in the first vertebra is referred to as a Jefferson fracture.

Craniocervical junction misalignment is also suspected as a factor in neurodegenerative diseases where altered CSF flow plays a part in the pathological process.

Hyperextension (Whiplash) Injury

A rear-end traffic collision or a poorly performed rugby tackle can both result in the head being whipped back on the shoulders, causing whiplash. In minor cases, the anterior longitudinal ligament of the spine is damaged which is acutely painful for the patient.

In more severe cases, fractures can occur to any of the cervical vertebrae as they are suddenly compressed by rapid deceleration. Again, since the vertebral foramen is large there is less chance of spinal cord involvement.

The worst-case scenario for these injuries is that dislocation or subluxation of the cervical vertebrae occurs. This often happens at the C2 level, where the body of C2 moves anteriorly with respect to C3. Such an injury may well lead to spinal cord involvement, and as a consequence quadriplegia or death may occur. More commonly, subluxation occurs at the C6/C7 level (50% of cases).

Additional images edit

-

Shape and position of atlas (shown in red), from above. The skull is shown in semi-transparent.

-

Atlas from above

-

3D image

-

Posterior atlantoöccipital membrane and atlantoaxial ligament (atlas visible at center)

-

Atlas from above

-

Atlas from above

-

Atlas, inferior surface

-

Computer generated 3D model of atlas

-

Skull and atlas of Niassodon

See also edit

References edit

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 99 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ "Table of Bones, Atlas". Dorland's Pocket Medical Dictionary (Abridged from Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary) (20th ed.). W. B. Saunders Companh. 1959. p. B-16. LCCN 98-578. Retrieved September 23, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Jackowe, David J.; Biener, Michael G. (June 2022). "Atlas and Talus". Journal of Anatomy. 240 (6): 1174–1178. doi:10.1111/joa.13613. ISSN 0021-8782.

- ^ Moulton, Andrew (2009). "Clinically Relevant Spinal Anatomy". Surgical Management of Spinal Deformities: 13–43. doi:10.1016/B978-141603372-1.50005-6. ISBN 9781416033721.

- ^ Gray, Henry (1924). Anatomy of the Human Body. Warren H. Lewis (edited and revised by) (21st ed.). Lea & Febiger. p. 97 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gray's Anatomy, pp. 36–37 (10/27/11)

- ^ "Atlas of Neuroradiologic Embryology, Anatomy, and Variants". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 24 (4): 774–775. 2003. ISSN 0195-6108. PMC 8148658.

- ^ Paraskevas, George; Mavrodi, Alexandra; Natsis, Konstantinos (2015-06-01). "Accessory mental foramen: an anatomical study on dry mandibles and review of the literature". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 19 (2): 177–181. doi:10.1007/s10006-014-0474-1. ISSN 1865-1569. PMID 25394607. S2CID 32194827.

- ^ Pękala, Przemysław A.; Henry, Brandon M.; Pękala, Jakub R.; Hsieh, Wan Chin; Vikse, Jens; Sanna, Beatrice; Walocha, Jerzy A.; Tubbs, R. Shane; Tomaszewski, Krzysztof A. (2017). "Prevalence of foramen arcuale and its clinical significance: a meta-analysis of 55,985 subjects". Journal of Neurosurgery. Spine. 27 (3): 276–290. doi:10.3171/2017.1.SPINE161092. ISSN 1547-5646. PMID 28621616.

- ^ Kwon, Jong Kyu; Kim, Myoung Soo; Lee, Ghi Jai (2009). "The Incidence and Clinical Implications of Congenital Defects of Atlantal Arch". Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 46 (6): 522–527. doi:10.3340/jkns.2009.46.6.522. ISSN 2005-3711. PMC 2803266. PMID 20062566.

- ^ Hummel, Edze; Groot, Jan C. de (2013-05-01). "Three cases of bipartition of the atlas". The Spine Journal. 13 (5): e1–e5. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.01.024. ISSN 1529-9430. PMID 23415018.

External links edit

- Netter, Frank. Atlas of Human Anatomy Archived 2017-11-20 at the Wayback Machine, "High Cervical Spine: C1–C2"