Archibald Willingham DeGraffenreid Clarendon Butt[1] (September 26, 1865 – April 15, 1912) was an American Army officer and aide to presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. After a few years as a newspaper reporter, he served two years as the First Secretary of the American embassy in Mexico. He was commissioned in the United States Volunteers in 1898 and served in the Quartermaster Corps during the Spanish–American War. After brief postings in Washington, D.C., and Cuba, he was appointed military aide to Republican presidents Roosevelt and Taft. He was a highly influential advisor on a wide range of topics to both men, and his writings are a major source of historical information on the presidencies. He died in the sinking of the British liner Titanic in 1912.

Archibald Butt | |

|---|---|

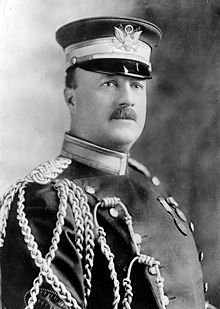

Butt in 1909 | |

| Born | Archibald Willingham DeGraffenreid Clarendon Butt September 26, 1865 Augusta, Georgia, U.S |

| Died | April 15, 1912 (aged 46) |

| Education | Sewanee: The University of the South |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, soldier, presidential aide |

Early life

editArchibald Butt was born in September 1865 in Augusta, Georgia, to Joshua Willingham Butt and Pamela Robertson Butt (née Boggs).[2] His grandfather, Archibald Butt, served in the American Revolutionary War. His great-grandfather, Josiah Butt, was a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army during the same conflict.[2] He was the nephew of General William R. Boggs of the Confederate States Army (CSA).[3] He had two older brothers (Edward and Lewis), a younger brother (John), and a sister (Clara),[4] and the family was poor.[5] Butt attended various local schools while growing up,[4] including Summerville Academy.[6] Butt's father died when he was 14 years old, and Butt went to work to support his mother, sister, and younger brother.[6] Pamela Butt wished for her son to enter the clergy.[4]

With the financial help of the Reverend Edwin G. Weed (who later became the Episcopal Bishop of Florida), Butt attended the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee.[6] His mother worked as a librarian at the university,[5] where she lived rent-free in an apartment in the library.[7] While in college, he became interested in journalism and eventually was named editor of the college newspaper. Butt became acquainted with John Breckinridge Castleman, a former CSA major and guerrilla fighter during the American Civil War and who was, by 1883, Adjutant General of the Kentucky Militia.[6] He joined the Delta Tau Delta fraternity (Beta Theta Chapter),[8] and graduated in 1888.[9]

After taking graduate level courses in Greek and Latin,[8] Butt traveled to Louisville, Kentucky, to meet with Castleman.[9] While in that city, he met Henry Watterson, founder of the Louisville Courier-Journal. Watterson hired him as a reporter, and Butt remained in Louisville for three years.[9] Butt left the Courier-Journal and worked for the Macon Telegraph for a year before moving to Washington, D.C.[10] He covered national affairs for several Southern newspapers, including the Atlanta Constitution, Augusta Chronicle, Nashville Banner, and Savannah Morning News.[11]

Butt was a popular figure in D.C. social circles, and made numerous important acquaintances during his time in the capital.[11] When former Senator Matt Ransom was appointed United States Ambassador to Mexico in August 1895, he asked Butt to be the embassy's First Secretary.[12] Butt wrote several articles for American magazines and published several novels while in Mexico.[11] He returned to the United States in 1897 after Ransom's term as ambassador ended.[citation needed]

Military service

editOn January 2, 1900,[13] Butt was commissioned as a captain in the United States Volunteers[9][14] (an all-volunteer group which was not part of the regular United States Army but was under the regular Army's control). He had long admired the military, and no one in his immediate family was serving in the armed forces at the time the Spanish–American War broke out. Although Butt's literary career was taking off, his family's long involvement with the military and his desire to represent his family in the army led him to enlist.[15] Adjutant General of the U.S. Army Henry Clarke Corbin was influential in encouraging him to enlist.[11][13]

Butt was assigned as an assistant quartermaster (i.e. a supply officer).[9] He was ordered to take the transport ship Sumner through the Suez Canal and proceed to the Philippines. But he was eager to get into the war, and secured a change in orders that sent him from San Francisco, aboard the USAT Dix. Butt's new orders required him to stop in Hawaii with his cargo of 500 mules. But he found the price of feed and stables so high and the quarters for the animals so poor that he disobeyed orders and continued on to the Philippines. Although this risked the lives of his animals (and possible court-martial), none of the mules died en route and Butt was praised for his initiative.[11][16] Butt remained in the Philippines until 1904, writing numerous treatises on the care of animals in the tropics and on military transportation and logistics. His reports won him significant praise by military officials.[17]

On June 30, 1901, Butt was discharged from the Volunteers and received a commission as a captain in the Regular Army retroactive to February 2, 1901.[18] Butt's social activities continued while he was in the Philippines. He was secretary of the Army and Navy Club,[11] and had a major role in founding the Military Order of the Carabao (a tongue-in-cheek spoof of military fraternal organizations that still exists as of 2012[update]).[19]

In 1904, Butt was ordered to return to Washington, D.C., where he was appointed depot quartermaster. He was the lowest-ranking officer ever to hold this important position within the Quartermaster Corps.[20] In 1906, when a revolution against Tomás Estrada Palma broke out in Cuba, Butt was hurriedly assigned to lead U.S. Army logistical operations there. On just two days' notice, he established a well-organized supply depot.[20] He was named Depot Quartermaster in Havana.[21]

Service to two presidents

editButt was recalled to Washington in March 1908. President Theodore Roosevelt asked him to serve as his military aide in April 1908[22]—just a month after Butt's return to the United States.[11] There were several reasons why Roosevelt chose Butt. Among them were that Roosevelt had become acquainted with Butt's organizational skills in the Philippines and was impressed by his hard work and thoughtfulness.[11] The other was that Taft recommended Butt, whom he knew well from their time together overseas.[9]

Butt became one of Roosevelt's closest companions.[23] Although Butt was stout, he and Roosevelt were constantly going climbing, hiking, horseback riding, running, swimming, and playing tennis.[24] Butt also quickly organized the chaotic White House receptions, transforming them from exhausting, hours-long events fraught with social missteps into efficient, orderly events.[11][25]

When William Howard Taft became president in March 1909, he asked Butt to stay on as military aide. Butt continued to serve as a social functionary for Taft, but he also proved to have strong negotiating skills and a good head for numbers, which enabled him to become Taft's de facto chief negotiator on federal budget issues.[20] Butt accompanied President Taft when he threw out the first ball at the first home game of Major League Baseball's Washington Senators in 1910 and 1911.[26] Butt died at sea shortly before the season-opening game in 1912 and Taft, according to The Washington Post, was overcome and "could not be present for obvious reasons."[27]

On March 3, 1911, Butt was promoted to the rank of major in the Quartermaster Corps,.[28]

By 1912, Taft's first term was coming to an end. Roosevelt, who had fallen out with Taft, was known to be considering a run for president against him. Close to both men and fiercely loyal, Butt began to suffer from depression and exhaustion.[29] Butt's housemate and friend Francis Davis Millet (himself one of Taft's circle) asked Taft to give him a leave of absence to recuperate before the presidential primaries began. Taft agreed and ordered Butt to go on vacation.[30] Butt was on no official business, but anti-Catholic newspapers and politicians accused Butt of being on a secret mission to win the support of Pope Pius X in the upcoming election.[31] Butt did intend to meet with Pius, and he carried with him a personal letter from Taft. But the letter merely thanked the pope for elevating three Americans to the rank of cardinal, and asked what the social protocol was for greeting them at functions.[9][32]

Sinking of the Titanic

editButt left on a six-week vacation in Europe on March 1, 1912, accompanied by Millet.[33][34] Butt booked first-class passage on the RMS Titanic to return to the United States. He boarded the ship at Southampton, in England on April 10, 1912; Millet boarded the ship at Cherbourg, France, later that same day. Butt was playing cards on the night of April 14 in the first-class smoking room when the Titanic struck an iceberg.[35] The ship sank two and a half hours later, with a loss of over 1,500 lives.[36] Butt and Millet were among the dead; Butt's body was never recovered.[37]

Butt's actions while the ship sank are largely unverified, but many accounts of a sensationalist nature were published by newspapers immediately after the disaster. One account had the ship's captain, Edward J. Smith, telling Butt that the ship was doomed, after which Butt began to act like a ship's officer and supervised the loading and lowering of lifeboats.[38] The New York Times also claimed that Butt herded women and children into lifeboats.[39] Another account said that Butt, a gun in his hand, prevented panicked male passengers from storming the lifeboats.[40] Yet another version of events said Butt yanked a man out of one of the lifeboats so that a woman could board. In this story, Butt declared, "Sorry, women will be attended to first or I'll break every damned bone in your body!"[40] One account tells of Butt preventing desperate steerage passengers from breaking into the first class areas in an attempt to escape the sinking ship.[40] Walter Lord's book A Night to Remember disagrees with claims that Butt acted like an officer. Lord says Butt most likely observed the ship's evacuation quietly.[41] Many newspapers repeated a story allegedly told by Marie Young. This tale says that Butt helped her into Lifeboat No. 8, tucked a blanket about her, and said, "Goodbye, Miss Young. Luck is with you. Will you kindly remember me to all the folks back home?" Young later wrote to President Taft denying she ever told such a story.[42]

Even Butt's final moments remain in dispute. Dr. Washington Dodge says he saw John Jacob Astor and Butt standing near the bridge as the ship went down.[43] Dodge's account is highly unlikely, as his lifeboat was more than 0.5 miles (0.80 km) away from the ship at the time it sank.[44] Other eyewitnesses say they saw him standing calmly on deck[45] or standing side by side with Astor waving goodbye.[46] Several accounts had Butt returning to the smoking room, where he stood quietly or resumed his card game.[47] But these accounts have been disputed by author John Maxtone-Graham.[48]

Funerals, memorials, and papers

editOn May 2, 1912, a memorial service was held in the Butt family home with 1,500 mourners, including President Taft, attending.[49] Taft spoke at the service, saying:[50]

If Archie could have selected a time to die he would have chosen the one God gave him. His life was spent in self–sacrifice, serving others. His forgetfulness of self had become a part of his nature. Everybody who knew him called him Archie. I couldn't prepare anything in advance to say here. I tried, but couldn't. He was too near me. He was loyal to my predecessor, Mr. Roosevelt, who selected him to be military aide, and to me he had become as a son or a brother.

At a second ceremony, held in Washington, D.C., on May 5, Taft broke down and wept, bringing his eulogy to an abrupt end.[49]

Memorials

editSeveral memorials to Butt were created over the years. A cenotaph was erected in the summer of 1913 in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.[51][52] Butt himself had selected the spot earlier.[53] In October 1913, the Butt-Millet Memorial Fountain, named for Archibald Butt and Francis Millet, was dedicated near the White House on the Ellipse.[54] In Augusta, Georgia, the Butt Memorial Bridge was dedicated in 1914 by Taft.[55][56] The Washington National Cathedral contains a large plaque dedicated to Major Archibald Butt; it can be found on the wall in the museum store.[57]

Sculptor Jorgen Dreyer was awarded a commission to create a sculpture to commemorate Butt. The commissioned piece, which Dreyer completed on June 15, 1912, was a bust of Butt situated on a base representing a ship on the ocean. The work was entitled The Message.

A government supply boat made of concrete was also named after Butt. It was one of nine experimental craft (all named for deceased members of the Quartermaster Corps) built by the Newport Shipbuilding Corporation in 1920 in New Bern, North Carolina.[58] It was sold to an aquarium in Miami, Florida, in 1934 and was later sunk or scuttled in Biscayne Bay.[59]

Papers

editDuring his time serving Roosevelt and Taft, Butt wrote almost daily letters to his sister Clara. These letters are a key source of information on the more private events of these two presidencies and provide insights into the respective characters of Roosevelt and Taft.[5][60] Donald E. Wilkes Jr., professor of law at the University of Georgia School of Law, has concluded, "All definitive biographies of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft necessarily rely on information in Archie's letters."[61] These letters (which overlap somewhat) have been published twice. The first collection, The Letters of Archie Butt, Personal Aide to President Roosevelt, was issued in 1924.[62] A second set of letters, Taft and Roosevelt: The Intimate Letters of Archie Butt, Military Aide, was published in two volumes in 1930 after Taft's death.[63]

Butt's letters are housed in the Georgia Department of Archives and History in Morrow, Georgia, with a microfilm set also residing at Emory University in Atlanta.[62][64]

Personal life

editButt lived in a large mansion at 2000 G Street NW[65] with the painter Francis Davis Millet, who also died in the sinking of the Titanic.[34] "Millet, my artist friend who lives with me" was Butt's designation for his companion. They were known for throwing spartan but large parties that were attended by members of Congress, justices of the Supreme Court, and President Taft himself.[25] The diplomat Archibald Clark Kerr, 1st Baron Inverchapel, who was bisexual,[66] lived with the couple when a young man.

A wide range of reasons were given why Butt never seemed interested in women. Chief among these was that Butt loved his own mother so much that there was little room for anyone else. Even Taft thought this explanation was true.[67] At the time of Butt's death, rumors swirled that he was about to lose his lifelong bachelor status. News accounts said he had a teenage mistress who either was carrying their unborn child or who had already given birth to a baby, or that Butt was engaged to a Colorado woman. None of these rumors were true.[68][69]

It has been presumed that Butt was homosexual. Historian Carl Sferrazza Anthony has written that Taft's explanation only "vaguely addressed" the real reason Butt failed to marry.[68] Davenport-Hines, however, believes Butt and Millet were gay lovers. He wrote in 2012:[25]

The enduring partnership of Butt and Millet was an early case of "Don't ask, don't tell." Washington insiders tried not to focus too closely on the men's relationship, but they recognized their mutual affection. And they were together in death as in life.

Historian James Gifford tentatively agrees. He points out that there is clear documentary evidence that Millet had at least one homosexual affair previously in his life (with the American writer Charles Warren Stoddard).[70] But any conclusion, Gifford says, must remain tentative:[71]

Of course there is no conclusive evidence that Archibald Butt was gay, and I find it highly unlikely, given Archie's careful self-image control, that he ever committed to paper any overt thoughts of such a nature. He was too canny an individual for that, too conscious of the risk in military and political ranks, where such an idea would have put a quick end to any hopes of advancement. So I can only suggest that my research results in an "impression" that he was homosexual.

Millet's body was recovered after the sinking and was buried in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts.[72]

Memberships

editIn 1911 Butt became a member of the Georgia Society of the Cincinnati by right of his descent from his great-grandfather Lieutenant Robert Moseley, a veteran of the American Revolution.[73]

Butt was also a member of the Army and Navy Club in Washington, D.C., the District of Columbia Society of Colonial Wars (number 3541), the District of Columbia Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (national number 16,412) and was a founding member of the Military Order of the Carabao.[74]

Military awards

editIn fiction

editButt appears and plays a significant role in Jack Finney's time travel novel, From Time to Time. In this novel, Butt is sent to Europe by President Taft and former President Roosevelt in an effort to stave off World War I. In Europe, he apparently gets the necessary assurances to make a European war impossible. However, even when informed of the ship's approaching sinking by the time traveling protagonist, he refuses to save himself and his mission when women and children will perish. His mission fails with his death.

James Walker's 1998 novel, Murder on the Titanic, includes Butt as a minor character.

Michael Bockman's 2012 novel, The Titanic Plan, features Archibald Butt as the major character in a historical-based novel involving leading industrialists and banking magnates of the day, and their plan to establish an illegal national commerce monopoly that would yield massive power and political influence to a few super-wealthy men.

Butt appears in the 2014 novel The Great Abraham Lincoln Pocket Watch Conspiracy by Jacopo della Quercia, where he is depicted as President Taft's closest friend and companion aboard a fictitious presidential dirigible "Airship One", which Butt pilots. The book uses period newspaper articles to report Butt's promotion from captain to major and even makes use of his letters to his sister Clara. Butt plays a major role in the story. His death is depicted as a climactic showdown between the United States and King Leopold II of Belgium aboard the Titanic.

In the 2021 time travel-themed novel A Quarter Past: Dancing With Disaster, Butt is explored as a major character, based on his writings and letters.

References

edit- ^ Smith, p. 69.

- ^ a b Matthews, p. 161.

- ^ Boyd, pp. viii–ix.

- ^ a b c Knight, p. 1457.

- ^ a b c "National Affairs: Dear Clara." Time September 15, 1930.

- ^ a b c d "Archibald W. Butt", in Butt, Both Sides of the Shield, p. xiii.

- ^ Abbott, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Macfarland, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Butt, Archibald Willingham DeGraffenreid", in The Encyclopedia of Louisville, p. 150.

- ^ "Archibald W. Butt", in Butt, Both Sides of the Shield, p. xiv.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Major Archibald Butt." New York Times April 16, 1912. Accessed May 18, 2012.

- ^ Abbott, p. xviii.

- ^ a b Hines, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Goode, p. 135.

- ^ "Archibald W. Butt", in Butt, Both Sides of the Shield, p. xv.

- ^ Bromley, p. 51.

- ^ "Archibald W. Butt", in Butt, Both Sides of the Shield, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ Butt's personal papers and memoirs claim the commission was made on January 2, 1900, which was the date of his commission in the Volunteers. But the commission was recommended by William Howard Taft, who was chairman of the Second Philippine Commission—the body which was organizing a civilian government in the Philippines in the wake of the Spanish–American War and the first battles of the Philippine–American War. Taft made the recommendation that Butt receive a commission in the Army to Secretary of War Elihu Root on January 7, 1901. In this matter it is important distinguish between a commission in the United States Volunteers and the Regular Army. See: Bromley, p. 52.

- ^ Roth, p. 256.

- ^ a b c Bromley, p. 52.

- ^ "Archibald W. Butt", in Butt, Both Sides of the Shield, p. xvii.

- ^ Gould, p. 208.

- ^ Morris, p. 529.

- ^ Watterson, p. 388.

- ^ a b c Davenport-Hines, Richard. "The History Page: Unsinkable Love." The Daily. March 20, 2012. Accessed May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Taft Tosses Ball." The Washington Post April 15, 1910; "Nationals Win, 8 to 5, as 16,000 Cheer Them." The Washington Post. April 13, 1911.

- ^ Duggan, Paul. "Balking at the First Pitch." The Washington Post. April 2, 2007. Archived June 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Accessed March 22, 2012.

- ^ United States Army Official Army Register for 1912, 1911, p. 23.

- ^ Abbott, pp. xi–x.

- ^ Garrison, p. 89.

- ^ Pringle, Henry F. (1939). The Life and Times of William Howard Taft. Vol. II. New York: Farrar & Rinehart. pp. 833–834.

- ^ Bromley, p. 326.

- ^ "Major Butt on Sick Leave." New York Times. March 1, 1912.

- ^ a b Brockell, Gillian (August 7, 2022). "Archibald Butt and Francis Millet died on Titanic. Were they a couple? - The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ Lynch, p. 84.

- ^ Mersey, Lord (1999) [1912]. The Loss of the Titanic, 1912. The Stationery Office. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-11-702403-8.

- ^ Schemmel, p. 148.

- ^ Caplan, pp. 55–57.

- ^ "The Tragedy of the Titanic—A Complete Story." New York Times. April 28, 1912.

- ^ a b c Caplan, p. 55.

- ^ Lord, p. 78.

- ^ Bromley, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Mowbray, p. 113.

- ^ Barczewski, p. 60.

- ^ Spignesi, p. 42.

- ^ Hines, p. 145.

- ^ Barczewski, p. 27.

- ^ Maxtone-Graham notes that if the eyewitnesses had been where they claimed, they would have had to travel aft and down a deck to loop through the smoking room, a highly improbable journey if they were seeking to abandon ship. See: Maxtone-Graham, p. 76.

- ^ a b "Taft in Tears as He Lauds Major Butt." New York Times. May 6, 1912.

- ^ Quote in Mowbray, p. xvi.

- ^ Peters, p. 217; "Monument for Major Butt, Titanic Victim." The Reporter. May 1913, p. 35.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 6625–6626). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Federal Official, Titanic Hero." Government Executive. April 11, 2012. Archived April 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Accessed May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Memorial to Titanic Dead." The Washington Post. October 26, 1913.

- ^ McDaniel, p. 108.

- ^ "Opening of Butt Memorial Bridge, Augusta, Georgia, April 14, 1914". Vanishing Georgia. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ "Archibald Butt Memorial Plaque". Great Lakes Titanic Society. Archived from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ "Atlantic Coast Notes." The American Marine Engineer. June 1920, p. 30.

- ^ Behre, Robert. "No Ifs, Ands, or Butts, It's Sawyer." The Post and Courier. February 13, 2012. Archived February 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Accessed April 13, 2012.

- ^ Gould, p. 224.

- ^ Wilkes, Jr., Donald E. "On the Titanic: Archie Butt" Archived August 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The Athens Observer April 28 – May 4, 1994, p. 6.] Accessed May 18, 2012.

- ^ a b O'Toole, p. 408.

- ^ Graff, p. 363.

- ^ Brewster, Hugh (2013). Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World. Broadway Books; Reprint edition. ISBN 978-0307984814.

- ^ "Maj. Butt's Home Sold" The Washington Post November 22, 1912.

- ^ Katja Hoyer, 'The danger-loving bisexual diplomat who tamed Joseph Stalin' The Telegraph, 30 April 2024; [1]

- ^ Taft, p. viii.

- ^ a b Anthony, p. 484.

- ^ "Archibald C. Butt Was to Have Been Married This Fall." The Denver Post April 18, 1912.

- ^ Prior, Will. "Historian Says Famous Titanic Passengers Were Gay." Gay Star News. April 13, 2012. Archived May 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Accessed May 18, 2012.

- ^ Gifford, James. "James Gifford: Archie Butt." OutHistory.org. April 1, 2012. Archived April 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Accessed May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Funeral Services for Millet." New York Times. May 2, 1912.

- ^ Thomas, 1929, p. 37.

- ^ General Society of Colonial Wars, p. 108; National Sons of the American Revolution, p. 16.

Bibliography

edit- Anthony, Carl Sferrazza. Nellie Taft: The Unconventional First Lady of the Ragtime Era. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006.

- Barczewski, Stephanie. Titanic: A Night Remembered. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006.

- Boyd, William K. "Introduction." in Boggs, William R. Military Reminiscences of Gen. Wm. R. Boggs, C.S.A. Durham, North Carolina: The Seeman Printery, 1913.

- Bromley, Michael L. William Howard Taft and the First Motoring Presidency, 1909–1913. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2003.

- "Butt, Archibald Willingham DeGraffenreid." In The Encyclopedia of Louisville. John E. Kleber, ed. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2001.

- Garrison, Webb B. A Treasury of Titanic Tales. Nashville, Tenn: Rutledge Hill Press, 1998.

- General Society of Colonial Wars. A Supplement to the General Register of the Society of Colonial Wars, A.D. 1906. Boston: General Society of Colonial Wars, 1906.

- Goode, James M. The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington, D.C.: A Comprehensive Historical Guide. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1974.

- Gould, Lewis L. American First Ladies: Their Lives and Their Legacy. Florence, Kentucky: Taylor & Francis, 2001.

- Graff, Henry Franklin. The Presidents: A Reference History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002.

- Hines, Stephen W. Titanic: One Newspaper, Seven Days, and the Truth That Shocked the World. Naperville, Ill.: Sourcebooks, 2011.

- Knight, Lucian Lamar. A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians. Chicago: Lewis Pub. Co., 1917.

- Lord, Walter. A Night to Remember. New York: Bantam Books, 1955. ISBN 0-553-27827-4

- Lynch, Don. Titanic: An Illustrated History. New York: Hyperion, 1993.

- Macfarland, Henry B.F. District of Columbia: Concise Biographies of Its Prominent and Representative Contemporary Citizens, and Valuable Statistical Data. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Press, 1909.

- Matthews, John. Complete American Armoury and Blue Book: Combining 1903, 1907 and 1911–23 Editions. Baltimore, Maryland: Clearfield Co., 1995.

- Maxtone-Graham, John. Titanic Tragedy: A New Look at the Lost Liner. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012.

- McDaniel, Jeanne M. North Augusta: James U. Jackson's Dream. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2005.

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex. New York: Modern Library, 2001.

- Mowbray, Jay Henry. Sinking of the Titanic: Eyewitness Accounts. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1998.

- National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Official Bulletin of the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution June 1912.

- O'Toole, Patricia. When Trumpets Call: Theodore Roosevelt After the White House. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

- Peters, James Edward. Arlington National Cemetery: Shrine to America's Heroes. Bethesda, Maryland: Woodbine House, 2000.

- Roth, Russell. Muddy Glory: America's Indian Wars in the Philippines, 1899–1935. West Hanover, Massachusetts: Christopher Pub. House, 1981.

- Schemmel, William. Georgia Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff. Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot Press, 2011.

- Smith, Elsdon Coles. The Story of Our Names. Detroit: Gale Research, 1970.

- Spignesi, Stephen J. The Titanic for Dummies. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Thomas, William Sturgis. Members of the Society of the Cincinnati, Original, Hereditary and Honorary: With a Brief Account of the Society's History and Aims. New York: T. A. Wright, 1929.

- United States Army. Official Army Register for 1912. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, December 1, 1911.

- Watterson, John Sayle. The Games Presidents Play: Sports and the Presidency. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Primary sources

edit- Butt, Archibald W. Taft and Roosevelt: The Intimate Letters of Archie Butt, Military Aide (2 vols. 1930), valuable primary source. vol 1 online also vol 2 online

- Abbott, Lawrence F. "Introduction." In Butt, Archibald Willingham. The Letters of Archie Butt, Personal Aide to President Roosevelt. Lawrence F. Abbott, ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1924.

- "Archibald W. Butt." (No author given.) In Butt, Archibald W. Both Sides of the Shield. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1912.

- Taft, William Howard. "Foreword." In Butt, Archibald W. Both Sides of the Shield. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1912.

External links

edit- Major Archibald Butt Writes Travel Agent Day Before Boarding Titanic[permanent dead link]

- Archibald W. Butt Papers. Georgia Department of Archives and History.

- Eulogy for Major Archibald Butt written by President William Howard Taft Archived April 30, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- "Archibald Willingham Butt letters, 1908–1912." Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. Emory University.

- 100 Years Ago Today: Major Archibald Butt, D.C. Resident, Boards Titanic for Transatlantic Crossing – Ghosts of DC blog

- Archibald W. Butt at Find a Grave

- Film footage including Major Butt at the 1909 Ft. Myer Virginia Army Trials for the Wright Brothers airplane; he appears as the soldier with high boots and gloves and Chaplin-like mustache: at 00:35, 01:05, 01:33–02:11 (joined by President Taft)