| Anglo-Egyptian War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the ʻUrabi revolt and Scramble for Africa and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire | |||||||

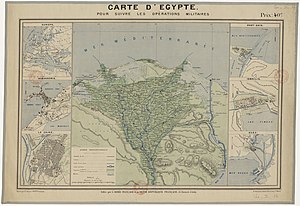

French map of the military operations in Egypt | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,560 regulars |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000–4,000 killed or wounded (British estimates)[3] | ||||||

The British conquest of Egypt (1882), also known as the Anglo-Egyptian War (Arabic: الاحتلال البريطاني لمصر, romanized: al-iḥtilāl al-Brīṭānī li-Miṣr, lit. 'British occupation of Egypt'), occurred in 1882 between Egyptian and Sudanese forces under Ahmed ‘Urabi and the United Kingdom. It ended a nationalist uprising against the Khedive Tewfik Pasha. It established firm British influence over Egypt at the expense of the Egyptians, the French, and the Ottoman Empire, whose already weak authority became nominal.

Background edit

In 1881, an Egyptian army officer, Ahmed ‘Urabi (then known in English as Arabi Pasha), mutinied and initiated a coup against Tewfik Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, because of grievances over disparities in pay between Egyptians and Europeans, as well as other concerns. In January 1882 the British and French governments sent a "Joint Note" to the Egyptian government, declaring their recognition of the Khedive's authority. On 20 May, British and French warships arrived off the coast of Alexandria. On 11 June, an anti-Christian riot occurred in Alexandria that killed 50 Europeans. Colonel ‘Urabi ordered his forces to put down the riot, but Europeans fled the city and ‘Urabi's army began fortifying the town. The French fleet was recalled to France. A British ultimatum was rejected, and its warships began a 10+1⁄2-hour bombardment of Alexandria on 11 July.

Reasons for the invasion edit

The reasons why the British government sent a fleet of ships to the coast of Alexandria is a point of historical debate. In their 1961 essay Africa and the Victorians, Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher argue that the British invasion was ordered to quell the perceived anarchy of the ‘Urabi Revolt, as well as to protect British control over the Suez Canal in order to maintain its shipping route to the Indian Ocean.[4]

A.G. Hopkins rejected Robinson and Gallagher's argument, citing original documents to claim that there was no perceived danger to the Suez Canal from the ‘Urabi movement, and that ‘Urabi and his forces were not chaotic "anarchists", but rather maintained law and order.[5]: 373–374 He alternatively argues that British Prime Minister William Gladstone's cabinet was motivated by protecting the interests of British bondholders with investments in Egypt as well as by pursuit of domestic political popularity. Hopkins cites the British investments in Egypt that grew massively leading into the 1880s, partially as a result of the Khedive's debt from construction of the Suez Canal, as well as the close links that existed between the British government and the economic sector.[5]: 379–380 He writes that Britain's economic interests occurred simultaneously with a desire within one element of the ruling Liberal Party for a militant foreign policy in order to gain the domestic political popularity that enabled it to compete with the Conservative Party.[5]: 382 Hopkins cites a letter from Edward Malet, the British consul general in Egypt at the time, to a member of the Gladstone cabinet offering his congratulations on the invasion: "You have fought the battle of all Christendom and history will acknowledge it. May I also venture to say that it has given the Liberal Party a new lease of popularity and power."[5]: 385

John Galbraith and Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid-Marsot make a similar argument to Hopkins, though their argument focuses on how individuals within the British government bureaucracy used their positions to make the invasion appear as a more favourable option. First, they describe a plot by Malet in which he portrayed the Egyptian government as unstable to his superiors in the cabinet.[6]: 477 On Galbraith and al-Sayyid-Marsot's reading, Malet naïvely expected he could convince the British to intimidate Egypt with a show of force without considering a full invasion or occupation as a possibility.[6]: 477–478 They also dwell on Admiral Beauchamp Seymour, who they claim hastened the start of the bombardment by exaggerating the danger posed to his ships by ‘Urabi's forces in his telegrams back to the British government.[6]: 485

Course of the war edit

British bombardment edit

The British fleet bombarded Alexandria from 11 to 13 July and then occupied it with marines. The British did not lose a single ship, but much of the city was destroyed by fires caused by explosive shells and, according to contemporary British sources, by ‘Urabists seeking to ruin the city that the British were taking over.[7] Tewfik Pasha, who had moved his court to Alexandria during the unrest, declared ‘Urabi a rebel and formally deposed him from his positions within the government.

‘Urabi's response edit

‘Urabi then reacted by obtaining a fatwa from Al Azhar shaykhs which condemned Tewfik as a traitor to both his country and religion, absolving those who fought against him. ‘Urabi also declared war on the United Kingdom and initiated conscription.

British order of battle edit

The British Army launched a probing attack at Kafr El Dawwar in an attempt to see if it was possible to reach Cairo through Alexandria. Afterwards, they determined it would not be possible to reach Cairo from this direction as Egyptian defences were too strong. In August, a British army of over 40,000, commanded by Garnet Wolseley, invaded the Suez Canal Zone. He was authorised to destroy 'Urabi's forces and clear the country of all other rebels.[citation needed][8]

The engineer troops had left England for Egypt in July and August 1882. The engineers included pontoon, railway and telegraph troops.[9]: 65

Wolseley saw the campaign as a logistical challenge as he did not believe the Egyptians would put up much resistance.[10]

Order of battle of the British Expeditionary Force

- Commander: Lieutenant General Sir Garnet Wolseley

- Chief of Staff: Lieutenant General Sir John Adye

|

|

Battle of Kafr El Dawwar edit

This battle took place on 5 August 1882 between an Egyptian army under Ahmed 'Urabi and British forces headed by Sir Archibald Alison. To ascertain the strength of the Egyptian's Kafr El Dawwar position, and to test local rumours that the Egyptians were retreating, Alison ordered a probing attack on the evening of the 5th. This action was reported by 'Urabi as a battle, and Cairo was full of the news that the advancing British had been repulsed; however most historians describe the action as a reconnaissance-in-force that was never intended to seriously assault Egyptian lines. Regardless, the British abandoned the idea of reaching Cairo from the north, and shifted their base of operations to Ismailia.

Wolseley arrived at Alexandria on 15 August and immediately began to move troops to and through the Suez Canal, to Ismailia, which was occupied on 20 August without resistance.[9]: 67

Battle of Tell El Kebir edit

Ismailia was quickly reinforced with 9,000 troops, with the engineers put to work repairing the railway line from Suez. A small force was pushed along the Sweet Water Canal to the Kassassin lock arriving on 26 August. There they met the enemy. Heavily outnumbered, the two battalions with four guns held their ground until some heavy cavalry arrived when the force went onto the offensive, forcing ‘Urabi to fall back 5 miles (8.0 km) with heavy casualties.[9]: 67–68

The main body of the army started to move up to Kassassin and planning for the battle at Tell El Kebir was undertaken. Skirmishing took place but did not interfere with the build-up. On 12 September, all was ready and during that night the army marched to battle.[9]: 68

On 13 September, ‘Urabi redeployed to defend Cairo against Wolseley. His main force dug in at Tell El Kebir, north of the railway and the Sweet Water Canal, both of which linked Cairo to Ismailia on the canal. The defences were hastily prepared as there was little time to arrange them. ‘Urabi's forces possessed 60 pieces of artillery and breech loading rifles. Wolseley made several personal reconnaissances, and determined that the Egyptians did not man outposts in front of their main defences at night, which made it possible for an attacking force to approach the defences under cover of darkness. Wolseley sent his force to approach the position by night and attacked frontally at dawn.

Surprise was not achieved; rifle fire and artillery from redoubts opened up when the range was 600 yards (550 m). Continuing the advance, the defending troops were hampered by the smoke from their weapons blocking their vision of the advancing British. The three battalions arrived in the enemy trenches all together and with little loss, resulting in a decisive victory for the British.[9]: 69

Officially losing only 57 troops while killing approximately two thousand Egyptians, the British army had more casualties due to heatstroke than enemy action.[10]: 130 The ‘Urabi forces were routed, and British cavalry pursued them and captured Cairo, which was undefended.

Power was then restored to the Khedive, the war was at an end and the majority of the British army went to Alexandria and took ship for home, leaving, from November, just an army of occupation.[9]: 69

Lieutenant William Mordaunt Marsh Edwards was awarded a Victoria Cross for his gallantry during the battle.

British military innovations edit

Railway edit

During the buildup to the battle at Tell El Kebir the specially raised 8th Railway Company RE operated trains carrying stores and troops, as well as repairing track. On the day of the battle (13 September) they ran a train into Tell El Kebir station between 8 and 9 am and "found it completely blocked with trains, full of the enemy's ammunition: the line strewn with dead and wounded, and our own soldiers swarming over the place almost mad for want of water" (extract from Captain Sidney Smith's diary). Once the station was cleared they began to ferry the wounded, prisoners and troops with stores to other destinations.[11]

Telegraph edit

In the wake of the advancing columns, telegraph lines were laid on either side of the Sweet Water canal. At 2 am on 13 September, Wolseley successfully sent a message to the Major General Sir Herbert Macpherson on the extreme left with the Indian Contingent and the Naval Brigade. At Tell El Kebir a field telegraph office was established in a saloon carriage, which Arabi Pasha had travelled in the day before. At 8:30 am on 13 September, after the victory at the battle of Tell El Kebir, Wolseley used the telegram to send messages of his victory to Queen Victoria; he received a reply from her at 9.15 am the same day. Once they had got connected to the permanent line, the Section also worked the Theiber sounder[further explanation needed] and the telephone.[11]

Army Post Office Corps edit

The forerunners of Royal Engineers (Postal Section) made their debut on this campaign. They were specially raised from the 24th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers (Post Office Rifles) and for the first time in British military history, post office clerks trained as soldiers provided a dedicated postal service to an army in the field. During the battle of Kassassin they became the first Volunteers to come under enemy fire.[12]

Aftermath edit

‘Urabi's trial edit

Prime Minister Gladstone initially sought to put ‘Urabi on trial and execute him, portraying him as "a self-seeking tyrant whose oppression of the Egyptian people still left him enough time, in his capacity as a latter-day Saladin, to massacre Christians." After glancing through his captured diaries and various other evidence, there was little with which to "demonize" ‘Urabi in a public trial. His charges were downgraded, after which he admitted to rebellion and was sent into exile.[5]: 384

British occupation edit

British troops then occupied Egypt until the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1922 and Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936, giving gradual control back to the government of Egypt.

Hopkins argues that Britain continued its occupation of Egypt after 1882 in order to guarantee British investments: "Britain had important interests to defend in Egypt and she was prepared to withdraw only if conditions guaranteeing the security of those interests were met—and they never were."[5]: 388 Consistent with this view, investment in Egypt increased during the British occupation, interest rates fell, and bond prices rose.[5]: 389

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Featherstone, Donald (1993). Tel El-Kebir 1882. Osprey Publishing. pp. 40–41.

- ^ There are no exact British casualty figures. The official War Office history gives a total of 83 killed, 607 wounded and 30 'missing', not including Royal Navy losses at Alexandria. Colonel J. F. Maurice, Military History of the Campaign of 1882 in Egypt (HMSO, 1887: new ed. 1908) Appendix VI. See, however, Peter Duckers, Egypt 1882: Dispatches, Casualties, Awards (Spink, 2001).

- ^ Wright, William (2009). A Tidy Little War: The British Invasion of Egypt, 1882. Spellmount.

- ^ Robinson, Ronald; Gallagher, John (1961). Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism. London: Macmillan.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hopkins, A. G. (July 1986). "The Victorians and Africa: A Reconsideration of the Occupation of Egypt, 1882". The Journal of African History. 27 (2): 363–391. doi:10.1017/S0021853700036719. JSTOR 181140. S2CID 162732269.

- ^ a b c Galbraith, John S.; al-Sayyid-Marsot, Afaf Lutfi (November 1978). "The British Occupation of Egypt: Another View". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 9 (4): 471–488. doi:10.1017/S0020743800030658. JSTOR 162074. S2CID 162397342.

- ^ "The Bombardment of Alexandria (1882)". Old Mersey Times. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Spiers, Edward (2018). Intervention in Egypt. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9781526137913.

- ^ a b c d e f Porter, Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers. Vol. II. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ^ a b Kochanski, Halik (January 1999). Sir Garnet Wolseley: Victorian Hero. A&C Black. ISBN 9781852851880.

- ^ a b Porter, Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- ^ Wells, Edward (1987). Mailshot – A History of the Forces Postal Services. London: Defence Postal & Courier Services. ISBN 0951300903.

Further reading edit

- Barthorp, Michael. The British Army on Campaign: vol 4: 1882–1902 (Osprey Publishing, 1988).

- Halvorson, D. "Prestige, prudence and public opinion in the 1882 British occupation of Egypt." Australian Journal of Politics and History (2010) 56#3, 423–440. online free

- Hopkins, Anthony G. "The Victorians and Africa: a reconsideration of the occupation of Egypt, 1882." Journal of African History 27.2 (1986): 363–391.

- Langer, William L. European alliances and alignments, 1871–1890 (1950) pp 251–80.

- Mowat, R.C. "From Liberalism to Imperialism: The Case of Egypt 1875–1887", Historical Journal, Vol 16, No.1 (Mar., 1973), pp. 109–124. online

- Mulligan, William. "Decisions for Empire: Revisiting the 1882 Occupation of Egypt." English Historical Review 135.572 (2020): 94–126.

- Newsinger, John. "Liberal Imperialism and the Occupation of Egypt in 1882." Race & Class 49.3 (2008): 54–75.

- Reid, Donald Malcolm. "The 'Urabi revolution and the British conquest, 1879–1882", in M.W. Daly, ed., The Cambridge History of Egypt, vol. 2: Modern Egypt, from 1517 to the end of the twentieth century (1998) pp. 217–238.

- Robinson, Ronald, and John Gallagher. Africa and the Victorians: The Climax of Imperialism (1961) pp 76–159. online

- al-Sayid-Marsot, A. "The Occupation of Egypt", in A. Porter (ed), The Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century: Volume III (Oxford, 1999)

- Schölch, Alexander. "The ‘Men on the Spot’ and the English Occupation of Egypt in 1882." Historical Journal 19.3 (1976): 773–785.

- Thomas, Martin, and Richard Toye. "Arguing about intervention: a comparison of British and French rhetoric surrounding the 1882 and 1956 invasions of Egypt." Historical Journal 58.4 (2015): 1081–1113.

Primary sources edit

- Cromer, Earl of. Modern Egypt (2 vol 1908) online free 1220pp, by a senior British official

- Malet, Edward. Egypt, 1879–1883 (London, 1909), by a senior British official online

External links edit

- Old Mersey Times. "The Bombardment of Alexandria" (1882)

- Autobiography of Sir John Stokes

- Fiorillo, Luigi. "Alexandria Bombardment of 1882 Photograph Album". American University in Cairo Rare Books and Special Collections Library.