Technology Support Net is the requisite physical, organizational, administrative, and cultural structures that support the development in technology. In order to function as technology, the technology core (hardware, software and brainware) needs to be ingrained in such kind of structure. It must be embedded in the supportive network of physical, informational, and socioeconomic relationships which enable and support the proper use and functioning of a given technology.

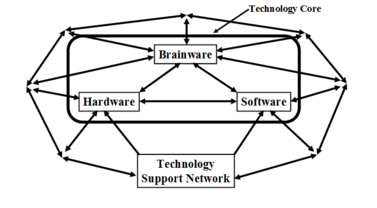

The entire structure of the technology core and its support network of requisite flows are sketched in Figure 1. It is clear that the shape and form of the Technology Support Net should be the main determinant of technology use.

Technology support network (TNS) is the primary criterion for technology innovation. Without matching the support network, any new technology has little chance of succeeding. The infrastructure of technology support net when fully established and fixed presents significant barriers to qualitative (paradigmatic) innovation. The process of innovation is no longer free and autonomous, but rather technically and politically subservient to the “holders and owners” of the support net.

Technology, as a kind of requisite support net, limits and predetermines the flows and types of innovation. Nowadays the processes of invention and innovation are not limited by lack of knowledge or too narrow business criteria, but by the existing supporting infrastructure. The focus is not so much on hardware (which is becoming commoditized), nor software or brainware, but on the boundaries and architecture of the support net itself.[1]

Functions of technology edit

In old times, at its most fundamental, technology is a tool used in transforming inputs into products or, more generally, towards achieving purposes or goals. For example, the inputs can be material, information or services. The product can be goods, services or information. Such a tool can be both physical (machine, computer) and logical (methodology, technique). Technology as a tool does not have to be from steel, wood or silica, it could also be a recipe, process or algorithm.

The nature of technology has changed in the global era during the development of human history: it is becoming more integrative and more knowledge-oriented, it is available all around the globe and it includes also logical schemes, procedures and software, not just tools and machinery. It tends to complement or extend the user, not to make him a simple appendage. In order to utilize technology efficiently and effectively, it should be viewed as a form of social relationship, with hardware and software being enabled by brainware and the requisite support infrastructure.

This is the view from Joseph Stiglitz, the recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) on technology transfer:

" History teaches us that transferring hardware is insufficient and ineffective. Codified technical information assumes a whole background of contextual knowledge and practices that might be very incomplete in a developing country. Implementing a new technology in a rather different environment is itself a creative act, not just a copied behavior. Getting a complex technical system to function near its norms and repairing it when it malfunctions are activities drawing upon a slowly accumulated reservoir of tacit knowledge that cannot be easily transferred or ‘downloaded’ to a developing country. "[2]

Stiglitz emphasize on the insufficiency of information (or codified “knowledge”) and the hardware-software mindset. Information can always be “downloaded”, knowledge cannot. Knowledge has to be produced within the local circumstances and structural support.

In recent times, Technology means a package of hardware, software, brainware – and primarily, the requisite support net which fixates, limits and predetermines the flows and types of innovation. In many modern technologies, the hardware is becoming a commodity, the least decisive component, a mere physical casing for the real power of effective knowledge contents. The enabling infrastructure, or technology support network, is often becoming the most important component of technology: in the near future it will not be the number of computers per capita, but the density and capacity of their network interconnectedness which will determine their effective usage.

Components of technology edit

Any technology can be divided into four recognizable components:

Hardware edit

The physical structure or logical layout, plant or equipment of machine or contrivance. This is the means to carry out required tasks of transformation to achieve purpose or goals. Hardware therefore refers not only to particular physical structure of components, but also to their logical layout.

Software edit

The set of rules, guidelines, and algorithms necessary for using the hardware (program, covenants, standards, rules of usage) to carry out the tasks. This is the know-how,[3] which means how to carry out tasks to achieve purpose or goals.

Brainware edit

The purpose (objectives and goals), reason and justification for using or deploying the hardware/software in a particular way. This is the know-what and the know-why of technology.[4] That is, the determination of what to use or deploy, when, where and why.

These three components form the technology core. The components of the technology core are co-determinant, their relations circular and mutually enhancing.

The interdependence among the three components is well illustrated in the example of automobile as technology: A car consists of its own physical structure and logical layout, its own hardware. Its software consists of operating rules of the push, turn, press, etc., described in manuals or acquired through learning. The brainware is supplied by the driver and includes decisions where to go, when, how fast, which way and why to use a car at all. Computers, satellites or the Internet can be defined in terms of these above three dimensions. Any information technology or system should also be clearly identifiable through its hardware, software and brainware.

Technology Support Net edit

TSN is a network of flows: materials, information, energies, skills, laws, rules of conduct that circulate to, through and from the network in order to enable the proper functioning of the technology core and the achieving of given purpose or goals. Ultimately, all the requisite network flows are initiated, maintained and consumed by people participating in the use and support of the use of a given technology. They might similarly and simultaneously participate in supporting many different technologies through many different TSNs.

Every unique technology core gives rise to a specific and requisite TSN and thus to a specific set of relationships among people. Ultimately, the TSN can be traced to and translated into the relationships among human participants: initiators, providers and maintainers of the requisite flows in cooperative social settings. In this sense, every technology is a form of a social relationship brought forth from the background environment.

The following example describes the various social relationships among people caused by technology support net.[5] As for the automobile technology, its TSN consists of an infrastructure of roads, bridges, facilities and traffic signals, but also of maintenance and emergency services, rules and laws of conduct, institutions of their enforcement, style and culture of driving behavior, etc. A large number of people have to be organized in a specific and requisite pattern in order to enable cars to function as technology. Moreover, technology and its four components could also be defined from the vantage point of its own user or observer, not in a context-free or absolute sense. In other words, roads, bridges and traffic signals can be technologies themselves, with their own hardware, software, brainware and support nets. For example, traffic lights are a part of the TSN of an automobile, but their own hardware can be driven by their own software (a computer-controlled switching program or schedule) and brainware (purposes of safety, volume and flow control, and interaction with pedestrians). This technology core has its own support net of electricity, signal interpretations and car traffic. So the traffic light is a technology of its own. Similarly, a piece of software from some technology can itself become viewed as technology, in order to achieve specific business purposes or goals with its own hardware, software, brainware and TSN.

High technology edit

High technology is a technology core that changes the very architecture (structure and organization) of the components of the technology support net. High technology therefore transforms the qualitative nature of tasks of TSN and their relations, as well as their requisite physical, energy and information flows. It also affects the skills required, the roles played, the styles of management and coordination – the organizational culture itself.

Because different changes in the technology core, both in hardware or software and brainware, will have differentiated effects on the requisite TSN, high technology is different from regular technology and appropriate technology core.

The regular technology core affects only the efficiency of flows over the TSN, i.e., it activates quantitative changes over the qualitatively identical architecture of the TSN. It allows users to perform the same tasks in the same way, but faster, more reliably, in larger quantities, or more efficiently, while preserving the qualitative nature of flows and the structure of the support, skills, styles and culture. Regular technology allows users to do the same thing, in the same way, but more efficiently. However, the appropriate technology core essentially preserves everything: the support net as well as the flows through it; its effects are neutral with respect to the TSN. It allows users to do the same thing in the same way at comparable levels of efficiency. Rather than improving the efficiency of performance, it is the preservation of the TSN itself which is the driving purpose of technology implementation.[6] Appropriate technology is very important in situations where the stability of the support net is primary for social, political, cultural or environmental reasons.

The comparison between technology and high technology is as following. While technology improves the functioning of a given system with respect to at least one criterion of performance, high technology breaks the direct comparability by changing the system itself, therefore requiring new measures and new assessments of its productivity. High technology cannot be compared and evaluated with the existing technology purely on the basis of cost, net present value or return on investment: it would be like comparing apples and oranges. Only within an unchanging and relatively stable TSN would such direct financial comparability be meaningful.

Life-cycle of high technology edit

Technology, being a form of social relationship, always evolves. No technology remains fixed. Technology starts, develops, persists, mutates, stagnates and declines – just like living organisms.[7] The evolutionary life-cycle occurs in the use and development of any technology. A new high technology core emerges and challenges existing TSNs which are thus forced to co-evolve with it. New versions of the core are being designed and fitted into an increasingly appropriate TSN, with smaller and smaller high-technology effects. High technology becomes just regular technology, with more efficient versions fitting the same support net. Finally, even the efficiency gains diminish, emphasis shifts to product tertiary attributes (appearance, style) and technology becomes TSN-preserving appropriate technology. This technological equilibrium state becomes fixated and stable, resisting to be interrupted by a technological mutation – new high technology appears and the cycle is repeated.

The automobile was high technology with respect to the horse carriage, it however evolved into technology and finally into appropriate technology with a stable, unchanging TSN. Main high-technology advance in the offing is some form of electric car – whether the energy source is the sun, hydrogen, water, air pressure or traditional charging outlet. Electric car preceded the gasoline automobile by many decades and now it returns to people's life to replace the traditional gasoline automobile.

In 2009, Milan Zeleny described the above phenomenon.[8] He also wrote that:

" Implementing high technology is often resisted. This resistance is well understood on the part of active participants in the requisite TSN. The electric car will be resisted by gas-station operators in the same way automated teller machines (ATMs) were resisted by bank tellers and automobiles by horsewhip makers. Technology does not qualitatively restructure the TSN and therefore will not be resisted and never has been resisted. Middle management resists business process reengineering because BPR represents a direct assault on the support net (coordinative hierarchy) they thrive on. Teamwork and multi-functionality is resisted by those whose TSN provides the comfort of narrow specialization and command-driven work. "[9]

Based on the framework, modern information and knowledge-based technologies currently tend to be high technologies with high-technology effects. They integrate task, labor and knowledge, transcend classical separation of mental and manual work, enhance systems aspects, and promote self-reliance, self-service, innovation and creativity.[10] In comparison, the “low” technologies, no matter how new, complex or advanced, are those which still require the dividing and splintering of task, labor and knowledge, increase specialization, promote division and dependency, sustain intermediaries and diminish initiative.

However, not all modern technologies are high technologies. They have to be used as high technologies, function as such, and be embedded in their requisite TSNs. They have to empower the individual because only through the individual can they empower knowledge. Not all information technologies have integrative effects. Some information systems are still designed to improve the traditional hierarchy of command and thus preserve and entrench the existing TSN. The administrative model of management, for instance, further aggravates division of task and labor, further specializes knowledge, and separates management from workers and concentrates information and knowledge in centers.

As knowledge surpasses capital, labor and raw materials as the dominant economic resource, technologies are also starting to reflect this shift. Technologies are rapidly shifting from centralized hierarchies to distributed networks. Nowadays knowledge is not residing in a super-mind, super-book or super-database, but a complex relational pattern of networks brought forth to coordinate human action.

Practical example edit

In practical world, the popularization of personal computers illustrates how the knowledge contributes to the ongoing technology innovation. The original centralized concept (one computer, many persons) is a knowledge-defying idea of the computing prehistory and its inadequacies and failures have become clearly apparent. The era of personal computing brought powerful computers “on every desk” (one person, one computer). This short and transitional period was necessary for getting used to the new computing environment, but was inadequate from the knowledge-producing vantage point. Adequate knowledge creation and management come mainly from networking and distributed computing: one person, many computers. Each person’s computer must form an access to the entire computing landscape or ecology through the Internet of other computers, databases, mainframes, as well as production, distribution and retailing facilities, etc. For the first time our technology empowers individuals rather than external hierarchies. It transfers influence and power where it optimally belongs: at the loci of the useful knowledge. Even though hierarchies and bureaucracies do not innovate, free and empowered individuals do, knowledge, innovation, spontaneity and self-reliance are becoming increasingly valued and promoted.[11]

Demands on high technology edit

As an important part of technology support net, a reigning business paradigm dictates the kinds of technology to be most likely accepted and marketed. The processes of recycling, resource recovery, material reduction, product reuse, remanufacture and systems redeployment lead to innovation and the reinstatement of the business life-cycle.[12] Business corporations seek technologies which fit and not disrupt their current management systems.

Eco-technology could be viewed as an emerging high technology that makes ecology as a good business.

References edit

- ^ Zeleny, Milan (2012). "High Technology and Barriers to Innovation: From Globalization to Localization". International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making. 11 (2). World Scientific: P 441. doi:10.1142/S021962201240010X.

- ^ Stiglitz, Joseph (1999). "PUBLIC POLICY FOR A KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY" (PDF). London, U.K.: The World Bank Department for Trade and Industry, Center for Economic Policy Research.

- ^ Zeleny, Milan (June). "Knowledge of Enterprise: Knowledge Management or Knowledge Technology?". International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making. 01 (2): P 181-190. doi:10.1142/S021962200200021X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zeleny, Milan (June). "Knowledge of Enterprise: Knowledge Management or Knowledge Technology?". International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making. 01 (2): P 190-207. doi:10.1142/S021962200200021X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chui, Michael (July 2012). "The social economy: Unlocking value and productivity through social technologies". McKinsey Global Institute.

- ^ Kotabe, Masaaki; Scott Swan, K. (1995). "The role of strategic alliances in high-technology new product development". Strategic Management Journal. 16 (8): 621–636. doi:10.1002/smj.4250160804.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Oliver, Gassmann (May 2006). "Opening up the innovation process: towards an agenda". R&D Management. 36 (3): P 223–366. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.2006.00437 (inactive 2023-08-02).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Zeleny, Milan (January 2009). "Technology and High Technology: Support Net and Barriers to Innovation". Advanced Management Systems. 01 (1): P 8-21.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Zeleny, Milan (September 2009). "Technology and High Technology: Support Net and Barriers to Innovation". Acta Mechanica Slovaca. 36 (1): P 6-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Manyika, James (May 2013). "Disruptive technologies: Advances that will transform life, business, and the global economy". McKinsey Global Institute.

- ^ Brown, Brad (March 2014). "Views from the front lines of the data-analytics revolution". McKinsey Quarterly.

- ^ Steven, Denning (November 2012). "Why The Paradigm Shift In Management Is So Difficult". Forbes.