Althoff, Gerd. Otto Iii. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003.

Davids, Adelbert. The Empress Theophano : Byzantium and the West at the Turn of the First Millennium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Herbert, Jan. Theophanu : Empress of the West. St. Albans: Three Abbeys, 2007.

MacLean, Simon. Ottonian Queenship. First Edition. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Wangerin, Laura. "Empress Theophanu, Sanctity, and Memory in Early Medieval Saxony." Central European History 47, no. 4 (2014): 716-36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43965083.

Thietmar of Merseberg

Improvements:

Make my sections sound less like history essays

start adding some of my sections to the article

start writing about her early life

include a section on her marriage charter (maybe? it's already another wikipedia article. talk to Ellen about this)

Early Life

editMarriage

editTheophanu was not the blue-blood that the Ottonians would have preferred; in fact, as the Saxon chronicler Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg, writes, the ottonian preference was Anna Porphyrogenita, a daughter of late Emperor Romanos II. Theophanu's uncle, though an emperor, John I Tzimiskes, was considered the usurper of the Byzantine throne. The match was ultimately made, on paper, to seal a treaty between the Holy Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire, but the niece of a usurper as the empress consort of the Holy Roman Empire was nonetheless, in the eyes of Otto I's advisors, an unfavorable decision. Otto I was told by some to send Theophanu away, on account of the notion that her questionable imperial origin would not legitimize the emperorship.[1] A reference by the Pope to Emperor Nikephoros II as "Emperor of the Greeks" in a letter while Otto's ambassador, Bishop Liutprand of Cremona, was at the Byzantine court, had destroyed the first round of negotiations.With the ascension of John I Tzimiskes, who had not been personally referred to other than as Roman Emperor, the treaty negotiations were able to resume. However, not until a third delegation led by Archbishop Gero of Cologne arrived in Constantinople, were they successfully completed. With the marriage contract completed, Otto I did not send Theophanu home, and in April 972 she was married to Otto II by Pope John XIII and crowned as Holy Roman Empress the same day in Rome. According to Karl Leysers' book Communications and Power in Medieval Europe: Carolingian and Ottonian, Otto I's choice was not "to be searched for in the parlance of high politics" as his decision was ultimately made on the basis of securing his dynasty with the birth of the next Ottonian emperor. [1]

Regency

editTheophanu ruled the Holy Roman Empire as regent for a span of five years, from May 885 to her death in 990, despite early opposition by the Ottonian court. The age of this Ottonian queenship was not without a boomerang effect. In fact, many queens in the tenth century, on a account of male rulers dying early deaths, found themselves in power, creating an age of women rulers for a small period of time. During her regency, Theophanu brought from her native east, a culture of royal women at the helm of some political power, something that the West had wholly rejected for centuries before her regency. Theophanu and her mother-in-law, Adelaide, are known during the empress' regency to butt heads frequently--Adelaide of Italy is even quoted in referring to her as "that Greek empress." [2] Theophanu's rivalry with her mother-in-law, according to historian and author Simon Maclean, is over-stated. Theophanu's "greekness" was not an overall issue, and furthermore, there was a grand fascination with the culture surrounding Byzantine court in the west that slighted most criticisms to her Greek origin.[2]

Theophanu did not remain merely as an image of the Ottonian empire, but as an influencer within the Holy Roman Empire. She intervened within the the governing of the empire a total of seventy-six times during the reign of her husband Otto II; perhaps a foreshadowing of her regency. [1]Her first act as regent was securing her son, Otto III, as the heir to the Holy Roman Empire. Theophanu also placed her daughters in power by giving them high positions in influential nunneries all around the Ottonian-ruled west, securing power for all her children.[1] She welcomed ambassadors, declaring herself "imperator" or "imperatrix." Though never donning any armor, she also waged war and sought peace agreements throughout her regency. [3] Theophanu's regency is a time of considerable peace, as the years 985-990 passed without major crises. Though, the myth of Theophanu's prowess as imperator could be an overstatement; according to historian Gerd Althoff, royal charters present evidence that magnates were at the core of governing the empire. Althoff remarks this as unusual, seeing that kings or emperors in the middle ages rarely shared such a large beacon of empirical power with nobility. [4]

Theophanu officially took over as regent in May 985 and ruled the Holy Roman Empire until her death in 990, including the lands of Italy and Lotharingia. By her prudent policies, she also was able to conclude peace with Duke Henry's former supporter Duke Mieszko I of Poland and to safeguard her son's interests. However, her ability to rule was hindered by a serious and life-threatening illness in the summer of 988. The illness damaged her health in the long term. Like the Byzantine empresses regnant Irene of Athens (752–803) and Theodora (815–867), who also had ruled for their underage sons, she issued diplomas in her own name as imperator augustus, "Emperor", the years of her reign being counted from the accession of her husband in 972.

By the winter of 989, Theophanu's health had significantly worsened. She eventually died at Nijmegen and was buried in the Church of St. Pantaleon near her wittum in Cologne. The chronicler Thietmar eulogized her as follows: "Though [Theophanu] was of the weak sex she possessed moderation, trustworthiness, and good manners. In this way she protected with male vigilance the royal power for her son, friendly with all those who were honest, but with terrifying superiority against rebels."

Because Otto III was still a child, his grandmother Adelaide of Italy took over the regency until Otto III became old enough to rule on his own.

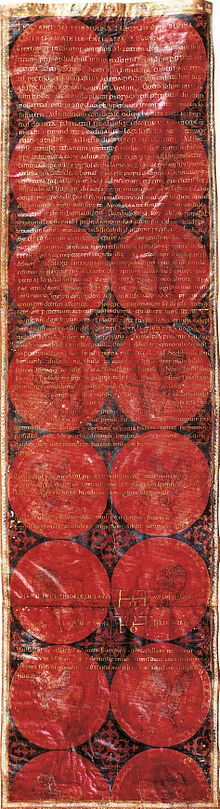

Marriage Charter

edit- ^ a b c d Leyser, Karl (1994). Communication and Power in Medieval Europe: The Carolingian and Ottonian Centuries. London, England: The Hambledon press. pp. 156–163. ISBN 1852850312.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ a b Maclean, Simom (2017). Ottonian Queenship. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978--0--19--880010--1.

- ^ Wangerin, Laura (December 2014). "Empress Theophanu, Sanctity, and Memory in Early Medieval Saxony". Central European History. 47: 716–717 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Althoff, Gerd (2003). Otto III. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 0-271-02232-9.