Photoanimation is a technique as old as the motion picture industry, in which still photos, artwork, or other objects are filmed with the use of an animation stand. On the Oxberry Master Series Stand,[1] the compound (platform) of the animation stand moves East-West and North-South or varying degrees of these parameters and tilts at angles up to 45 degrees in any direction with combinations that cover the compass rose. In the meantime the camera, mounted to a steel track, moves up and down relative to the subject being filmed. The E-W/N-S movement combinations and scans are done with a motorized compound that rotates and tilts. Backlighting can also be applied beneath the compound platform to create special visual effects.

Usage

editOxberry Master Series animation camera stand filming made possible the pinnacle of the application of this technique and it was brought to a high art form and technique by writer-director

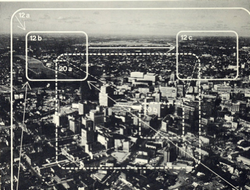

Raúl daSilva working with camera stand operator, Francis Lee, in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s for communication, instruction, promotional and advertising motion pictures. The June 1969 issue of American Cinematographer, the magazine for the American Society of Cinematographers, contains a cover story written by Raúl daSilva on the art of Photoanimation (see cover insert) with a comprehensive description of the possibilities of this craft[2].

In making such films the soundtrack is first produced, analyzed and bar sheets made depicting the soundtrack details. Exposure sheets for filming (camera exposures) are then abstracted from the bar sheets.

When skill and planning are applied one can take a series of stills and/or objects through a combination of movements blended with a compilation of photographic effects. One of the most elaborate examples of complex, combined photoanimation shooting is demonstrated in Raúl daSilva’s critically acclaimed, six-time international film festival prizewinner, Rime of the Ancient Mariner with Sir Michael Redgrave which was produced between the years 1973 and 1975. In this film the director brings together the art of several illustrators spread throughout two centuries, artists who attempted to breathe life into the epic poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Not only is there a seminal display of the collected art work but through the photoanimation technique combined with sound and music a very unique visualization of the poem was created. Photoanimation techniques, as stated above, were used from the very early days of motion pictures but not at this level of sophistication and complexity. Hollywood often leaned on this less expensive technique for some of its movie trailers in the early era.

From the 1980s on filmmaker Ken Burns (The Civil War and other films for PBS) popularized a simpler, less complex form of photoanimation later called the Ken Burns Effect.

References

edit- ^ Oxberry Cameras

- ^ American Cinematographer, June 1969