Armenian historiography is a set of works by Armenian authors (annals, chronicles, etc.), dedicated to the history of Armenia itself and its' neighbouring countries and regions – the Caucasus, Byzantine Empire and the Middle East.[1][2]

The oldest Armenian sources were written in the first centuries A.D., and have left valuable historical resources for modern scholars. In late antiquity mighty Armenian families, such as the Mamikonean, hired historians to put down the history of Armenia, their families and their own deeds.[3] This was in sharp contrast with neighbouring Persia, where the Sassanian rulers held monopoly on recording the past.[3] However, most Armenian histories from this period were composed by the church authorities, with history of Armenian Church in mind.[3] Thus early historical books were strongly influenced by the Christian worldview.[3]

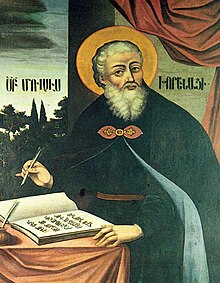

Movses Khorenatsi is credited with the first known historiographical work on Armenia, called Chronicle of the Armenians, written in 474.[4] Mediaeval Armenian historiography is considered the most robust among the Middle Eastern countries.[5] It was heavily influenced by Armenian theology, notably by the spirituality of martyrdom, in many aspects a central concept to contemporary Armenian culture.[5] It is visible in the works of Faustus of Byzantium, Elisaeus (Ełišē) and Sebeos[5]. In addition to documenting the history of Armenia, those historians also focused on deeply religious topics such as the Chosen people, the role of the church in the world or Christian mysteries.[5] Another early historian relating semi-mythical beginnings of Armenian statehood and Christianisation of Armenia was Zenob Glak, a 4th century scholar whose work was expanded by Hovhan Mamikonian in the 7th century into The History of Taron, a historical romance detailing the history of the region of Taron through the Perso-Byzantine wars that lasted five generations[6]: 100–101 .

Another line of histories influencing future generations of Armenian historical writers stems from Faustus of Byzantium, a 5th century author of five volumes detailing the history of Armenia from the earliest times to the reign of king Arsaces II.[6]. His work was then updated and continued by Ghazar Parpetsi, whose History of Armenia details the most recent history of the country: from mid-fourth century Sasanian rulers until the death of Sahak Partev and Mesrop Mashtots a century later (volume I), then the events surrounding the battle of Avarayr (volume II) and Vartanank wars and the 484 signing of the Nvarsak_Treaty.[6]: 215–6 Apart from Faustus of Byzantium, Parpetsi also used works of other historians, including Agathangelos, Koryun, and apparently Eusebius of Caesarea's Historia Ecclesiastica.[7]

Notable Armenian historians also include Stephen Orbelian and others.[8]

A new upsurge in the Armenian historiography covered the 12th and 13th centuries, a period when the major works of Hovhannes Draskhanakerttsi were created, when no less than 10 major works detailing the Mongol invasions of the Caucassus and the Armenian-Mongol relations during the Mongol rule of the area were written[9]. This period is considered one of the richest epochs in Armenian historiography.[9]

Armenian alphabet

editArmenian historiography started in the middle of 5th century A.D., after the creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots. The most important Armenian historiographs in early Middle Ages (V-X c.) were Movses Khorenatsi, Lazar Parpetsi, Faust Buzand, Egishe, Cebeos and others.

Koryun, "The Life of Mashtots" (Classical), the playwright, which is the main source of information about the Armenian alphabet.

See also

editwikidata: Q4069708

References

edit- ^ Vauchez, Andre (2000). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 108. ISBN 9781579582821.

- ^ Al-Bakhit, M. A., ed. (2003-01-01). History of Humanity – Vol. IV – From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century: From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century (in Russian). UNESCO. p. 260. ISBN 9789234028134.

- ^ a b c d Daryaee, Touraj (2013-11-30). "Historiography in late antique Iran". In Ansari, Ali M. (ed.). Perceptions of Iran: History, Myths and Nationalism from Medieval Persia to the Islamic Republic. I.B.Tauris. p. 68. ISBN 9781848858305.

- ^ Matevosyan, Artashes S. (1989). Մովսես Խորենացին և Աթանաս Տարոնացու Ժամանակագրությունը [Movses Khorenatsi and Atanas Taronatsi's Chronicle]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes, vol. 124 (in Armenian). p. 226.

- ^ a b c d Zekiyan, Boghos Levon (2006). "Armenian Spirituality: Some Main Features and Inner Dynamics". In Ervine, Roberta R. (ed.). Worship Traditions in Armenia and the Neighboring Christian East: An International Symposium in Honor of the 40th Anniversary of St. Nersess Armenian Seminary. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 268. ISBN 9780881413045.

- ^ a b c Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2000). The heritage of Armenian literature. Vol. 1: From the oral tradition to the golden age. Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press. pp. 213–216. ISBN 0814328156. OCLC 924052018.

- ^ Bedrosian, Robert (1985), "Ghazar P'arpec'i's History of the Armenians: Translator's Preface", Robert Bedrosian’s Homepage., New York, archived from the original on 2013-11-13

- ^ Armenian Historiography, visited on 27 August 2016

- ^ a b Atwood, Christopher P. (2012-05-01). "The Mongols and the Armenians (1220–1335). By Bayarsaikhan Dashdondog. Leiden: Brill, 2011. xii, 267 pp. $132.00 (cloth)". The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (02): 541–542. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000344. ISSN 1752-0401.