Images

Edit to the lead (on Killian's recommendation):

Original lead: A wildcat strike action, often referred to as a wildcat strike, is a strike action undertaken by unionized workers without union leadership's authorization, support, or approval; this is sometimes termed an unofficial industrial action.

Addition: The legality of wildcat strikes varies between countries and over time, although they are not typically criminal offenses.

From "Taft-Hartley Act of 1947" under "United States of America", under "By country"

editOriginal text: The National Labor Relations Act’s Supreme Court confirmation in 1937 became a point around which corporate interests could rally in defense of business, with the ultimate goal of limiting the degree to which the act, and other legislation, could extend power to workers.

Edited version: After a challenge by the American Liberty League, the National Labor Relations Act’s Supreme Court confirmation in 1937 became a point around which corporate interests could rally in defense of business, with the ultimate goal of limiting the degree to which the act, and other legislation, could extend power to workers.

Additionally, there was a concern raised that a pre-existing statement in the article was biased because it did not make mention of an obligation that unions have to employers. The statement in question is: "Some strikes that begin as wildcat actions, such as the Memphis Sanitation Strike and Baltimore municipal strike of 1974, are later supported by their respective unions' leadership (who then begin fulfilling their obligation to collectively bargain for their worker-members)."

However, I disagree with the notion that union leaders have an obligation to employers beyond what is dictated by the law. Unions are not brokers between labor and employer, but representatives of labor that are obligated only to pursue labor’s best interest. Their job is not to strike a balance between what is most beneficial to the employer and the employee - that’s just the product of negotiations, and is why unions negotiate with employers (and are not empowered to make a final decision on their own). Were this in reference to the NLRB, I could agree that there would be an omission in describing the obligation towards workers but not towards employers.

The below has mostly been moved to the mainspace already. There may have been some minor alterations made that are reflected there but not here.

editBackground

editThe motivation for wildcat strikes in the United States changed from the Depression era to the Postwar era in response to a variety of factors relating to businesses, the federal government, and unions.

Union coordination with working class interests

editDuring the Depression, and prior to the bureaucratization of unions, leaders of different political philosophies tended to agree on the necessity and unique capabilities of local strike actions. Regardless of the organizational structure and direction, unions had no difficulty retaining these kinds of tactics within their toolkit.[1] With the ascent of the Roosevelt administration, labor found a powerful ally in the struggle for workers' rights. With the changing role of the National Labor Relations Board, as determined by the New Deal National Labor Relations Act (shortened to NLRA, and also referred to as the Wagner Act) of 1935, a specific government entity began arbitrating grievances between workers, their unions, and employers. This represented a significant shift in governmental intervention in labor struggles.[2]

Changes in union objectives

editThe United States' entry into World War II marked a critical shift in the role of unions in strike actions. The alliance between unions and Roosevelt's federal government meant that major unions like the Congress of Industrial Organization and the American Federation of Labor made an oath against striking for the war’s duration in order to prevent disruption of wartime production, a show of labor's willingness to patriotically cooperate. However, both support and anxiety around this decision could be found within union leadership. Operating without a weapon to use when issues might go unresolved, and knowing that unions had voluntarily surrendered the weapon, posed a major threat to organizing labor during the war.[1] Another concern that union leadership had was with its Communist members and other firebrands, as potentially inviting harsh repercussions from unity-minded politicians could underscore the inadequate strength of the labor movement to follow through on endangering production.[3] Additionally, the political climate of wartime America and post-war America favored a bureaucratic union culture that adhered to an orthodoxy of institutional reform around relatively narrow objectives. Of increasing importance to union leadership was an alliance with the Democratic establishment, which demanded stricter control over union members and actions in exchange for some degree of political support in institutionalizing unions. Part of this emergent anti-radical platform was an easy embrace of the Taft-Hartley Act’s anti-communist agenda, resulting in virtually all Communists losing their union positions in only a couple years.[3]

An early example of the tension between the substantially changing unions and their members can be seen in the wildcat strikes against Little Steel companies in 1941. Bethlehem Steel Corporation, Republic Steel, Youngstown Sheet & Tube, and US Steel (collectively referred to as "Little Steel") experienced a series of these strikes during the spring of 1941 in spite of strides in union-employer relations made under the oversight of NLRB and with the support of federal wartime programs. Little Steel had found that the benefits of federal profit guarantees made submitting to labor demands more viable. However, many of these springtime strikers held grievances with their own unions for an over-cooperative wartime attitude that placed greater value on New Deal institutions and programs than on disruptive actions to secure local concessions. A critical point of contention lay in the “no-strike pledge” that unions committed their membership to in response to wartime nationalism. As the war progressed, the emphasis on union-NLRB relations led to frequent and dispersed wildcat strikes in the steel industry; the new paradigm empowered union leaders over common members such that workers felt they had to take matters into their own hands, even if it meant risking expulsion from the union.[4]

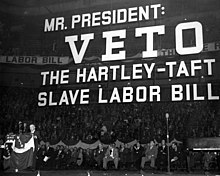

Taft-Hartley Act of 1947

editThe National Labor Relations Act’s Supreme Court confirmation in 1937 became a point around which corporate interests could rally in defense of business, with the ultimate goal of limiting the degree to which the act, and other legislation, could extend power to workers.[5] The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act emerged partially as a consequence of the Little Steel Strike of 1937 and as a means to re-tool the NLRA away from labor protections and towards business protections. The earlier (and failed) Smith Bill of 1940 was used as a basis for reducing the culpability of companies in slow or non-resolving conflicts with labor, delegitimizing labor’s right to strike without risking employment, and for placing greater responsibility on unions for the actions of their members.[4] Taft-Hartley also included many clauses built to disempower unions, whether by guaranteeing workers the ability to work in union workplaces without membership, exclude a large number of employment statuses from inclusion in unions, or widening who qualified as a manager (notably, foremen and supervisors, who could not longer join unions as a result of this same act).[5] The act helped to disunify unions across different industries, and even within industries, while supporting the development of a managerial class within workplaces to protect employers from union action.[3] It also set off a wave of state-level anti-unionism that popularized the notion of union-free zones, providing a potent weapon to businesses facing union demands: the threat of relocation.[5]

Postwar disillusionment with unions

editDuring the postwar boom, union achievement of benefits for only some employees succeeded in removing pressure from their membership as a whole, and demotivated radical action from those who had gained the most. With solidarity and sympathy striking effectively broken, unions had failed to bring universal benefits to their members, and had certainly failed to benefit workers’ rights for non-unionized workers.[3]

Legality

editContemporary instances

edit- ^ a b Green, James R., 1944-2016. (1983). Workers' struggles, past and present : a "Radical America" reader. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-4399-1784-1. OCLC 1060587482.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Sparrow, Bartholomew H. (2014). From the Outside In : World War II and the American State. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6421-8. OCLC 884012522.

- ^ a b c d Lichtenstein, Nelson. (2010). Labor's War At Home : the CIO in World War II. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-0423-7. OCLC 806203257.

- ^ a b White, Ahmed, VerfasserIn. (2016). The last great strike : Little Steel, the CIO, and the struggle for labor rights in New Deal America. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-96101-2. OCLC 1030354396.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Feurer, Rosemary; Pearson, Chad, eds. (2017-03-15). Against Labor. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-04081-8.