Hellenistic portraiture is one of the greatest achievements of Greek art. It is indisputable that during the Hellenistic period artists created physiognomic portraits (that reproduced the exact physical features of the subjects) and also gave an insight into their psyche. Although only sculptures remain, it is believed that this new way of portraiture was reflected in paintings[1] as well.

Effigies using only idealized facial features were common until the 4th century BC. These so-called "typological" portraits (where the features reflected the social ranking of the subject) reflect the collective function of art: it had to serve the polis, rather than the individuals. The showing of "private" images in public places was prohibited, and images of illustrious men had to undergo a careful examination.

Until the late Hellenistic period, Greek statuary was only whole figures or, during the latter part of the period or in peripheral areas, half figures most commonly used in funerary art. Today, the portraits we often associate with ancient art are actually Roman copies and not Greek originals. Copying Greek art was common practice among the Romans at that time. Even the portraits on hermae were copied by the Romans from the original Greek whole figures.

Lysippos edit

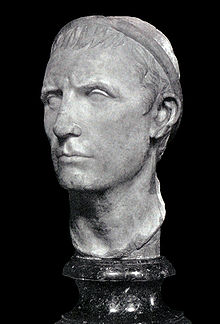

The changes in social and cultural conditions of the time, along with Lysippos’ big personality, allowed him to overcome the last reticence towards physiognomic portraiture, and to begin faithful representations of the somatic traits and spirit of the subjects of his work. In the bust of Alexander the Great he transformed the ruler’s physical defect that required him to keep his head bent sideways and upwards, into a seemingly celestial rapture, making it appear as though he was having “a silent conversation with the divinity”[2]. This sculpture was the template for the “inspired” sovereign portrait which had a lasting influence in official portraiture well beyond the Hellenistic period.

The portrait of Aristotle (completed while the philosopher was still alive), the reconstructed portrait of Socrates type II, and the portrait of Euripides done in a “Farnese” style are all also attributed to Lysippos or his circle. A strong psychological connotation is present in these works, consistent with the merits of the subjects in their real lives.

-

Alexander the Great, from the Louvre

-

Socrates II

-

Lysippos' Aristotle

-

"Farnese" Euripides

Development of the physiognomic portraiture edit

After Lysippos, between the 2nd and 1st century BC, a large development in Greek physiognomic portraiture occurred. It no longer was only for sovereigns and particularly illustrious men, but also for common people. Art became available to individuals and no longer exclusively to the greater public. During this period, honorary portraiture and funerary portraiture also grew in popularity.

According to sources, Lysippos’ brother Lysistratus would take castings of faces with plaster, from which he created wax models. He would then use the wax models to create bronze castings. Pliny referred to the works as realistic to the detriment of compositional harmony and correctness of form. After all, part of the draw of Hellenistic art was celebrating specific, albeit deformed, aspects of reality.

Some of the masterpieces of this period are the portraits of Demosthenes and of Hermarchus, based on the actual physical features of the subjects (280-270 BC). Also among the masterpieces are the portrait of an elder 351 (200 BC) from the National Archeological Museum of Athens, the bronze head of Antikythera (Athens, circa 180-170 BC), and the portrait of suffering Euthydemos I of Bactria. The reconstructed portrait of the Pseudo-Seneca of Naples is a great example of this realistic style.

Official portraiture edit

In official portraits, instead of following the purely "realistic" stylistic trend, sculptures were given hieratic and detached expressions reflecting their divine ancestry and a nobler, more dignified look. The best examples of this are the portraits of Antiochus III of Syria, Ptolemy III Euergetes, Berenice II, Ptolemy VI, and Mithridates VI.

The bronze statue Juba II which is also found in other Alexandrian marble statues, can be ascribed to this same trend.

Other images edit

-

Pseudo-Seneca at Naples

-

Portrait of Demosthenes

-

The Philosopher of Antikythera at the Archeological Museum of Athens

Bibliography edit

- Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, Il problema del ritratto, in L'arte classica, Rome, Editori Riuniti, 1984.

- Pierluigi De Vecchi and Elda Cerchiari, I tempi dell'arte, vol.1, Milan, Bompiani, 1999, ISBN 88-451-7107-8.

- Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, Jeannine Auboyer, Ritratto, in Enciclopedia dell'Arte Antica, Rome, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia italiana Treccani, 1965.

- Stefano Ferrari, La psicologia del ritratto nell'arte e nella letteratura, Bari-Roma, Laterza Editori, 1998.

Related items edit

- ^ Plinio Segundo, Cayo, 0023-0079. (1958–1999). Natural history. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99364-0. OCLC 928107039.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bianchi Bandinelli, Ranuccio". Der Neue Pauly Supplemente I Online - Band 6: Geschichte der Altertumswissenschaften: Biographisches Lexikon. Retrieved 2019-11-29.