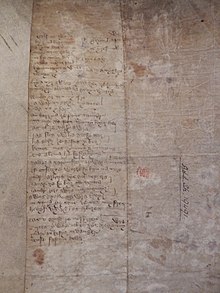

The Charter Fragment, ca. 1400

edit

The Charter Fragment is a short poem about marriage, believed to be the earliest extant connected text in the language. It was identified in 1877 by Henry Jenner among charters from Cornwall in the British Museum and published by Jenner and by Whitley Stokes.[1]

|

Golsoug ty coweȝ Hy a vyȝ gwreg ty da Lemen yȝ torn my as re my ad pes worty byȝ da

ken es mos ȝymmo ymmyug

Dallaȝ avar in freȝ darwar Maraȝ herg ȝys gul nep tra Ras o ganso ren offeren |

Goslow, ty goweth; Hy a vÿdh gwreg ty dhâ Lemmyn i’th torn me a’s re My a’th pës worty bÿdh dâ,

Kyn ès mos dhymmo, emmowgh.

Dallath avarr; yn freth darwar Mara’th ergh dhis gul neb tra, Ras o ganso, ren Oferen. |

Translation [The older man speaks to the young man] Listen, you comrade; She will be a good wife, Now into your hand I place her I beg you be good to her, [The older man speaks to them both] Before I go, kiss. [The older man speaks to the girl] Begin early; be assiduously careful If he ask you to do anything, He was gracious, by the Mass. |

Kernowek Standard

editOrthography

editKernowek Standard implements an orthography which is historically based and which recognizes the actual pronunciations found in Revived Cornish. Its devisors note that most RC pronunciation, even by users of Kernowek Kemmyn orthography, owes much to the pronunciation of Unified Cornish. The close distinction made by the SWF between Revived Middle Cornish (RMC), Tudor Cornish (TC) and Revived Late Cornish (RLC) is perhaps too granular, particularly where the SWF posits phonemes for RMC which are (1) at odds with UC and (2) "aspirational" distinctions based on the theories behind Kernowek Kemmyn but which few if any speakers make.

Monophthongs

editUnstressed vowels are always short. Stressed vowels in monosyllables are long when word-final or when followed by a voiced consonant, e.g. gwag [gwæːg] 'empty', lo [loː] ('spoon'), and short when followed by a double consonant or a consonant cluster, e.g. ass RMC [as], RLC [æs] ('how'); hons RMC [hɔns], RLC [hɔnz] ('yonder'). Exceptions are that long vowels precede st, e.g. lost RMC [lɔːst], RLC [loːst] ('tail'), and also sk and sp in RMC, e.g. Pask [paːsk] ('Easter'). Stressed vowels in polysyllables are short except in the case of conservative RMC speakers, who may pronounce vowels long before single consonants and st (and, for some, sk and sp), e.g. gwagen RMC [gwa(ː)gɛn], RLC [gwægɐn] ('a blank').

Letter RMC TC & RLC Short Long Short Long a [a] [aː] [æ]1 [æː] e [ɛ] [ɛː] [ɛ]1 [eː] eu [œ]2 [øː]3 [ɛ] [eː] i [i] [iː] [ɪ] [iː]4 o5 [ɔ], [ɤ] [ɔː] [ɔ]1, [ɤ]1 [oː] oa6 - - - [ɒː] oo7 - [oː] - [oː], [uː]8 ou [u] [uː] [ʊ]1 [uː] u [ʏ]9 [yː] [ɪ]10 [iː]10 y11 [ɪ] [ɪː] [ɪ] [iː]

^1 May be reduced to [ɐ] when unstressed, which is given as [ə] in the original Specification[2] but as [ɐ] in the updated online dictionary.[3]

^2 Unrounded to [ɛ] when unstressed.[2]

^3 Given as [œ] in the original Specification[2] but as [øː] in the updated online dictionary.[4]

^4 Often realised as [əɪ] in RLC in stressed open syllables, in which case it is written with the variant graph ei.

^5 Can either represent [ɔ], the short version of long o [ɔː/oː], or [ɤ], the short counterpart to oo [oː/uː]. When representing [ɤ], the 2013 Review suggests o could be written as ò for clarity in "dictionaries and teaching materials".[5]

^6 Used as a variant graph by RLC speakers in a few words where RMC and TC speakers use long a, [aː] and [æː] respectively. After the 2013 Review, used solely in boas ('be'), broas ('big'), doas ('come'), moas ('go') and their derivatives.[5]

^7 Used in word only when both Kernewek Kemmyn (KK) writes oe and RLC realises the sound [uː]. Therefore, oo does not always correspond to KK, e.g. SWF loor, KK loer ('moon') both [loːr], but SWF hwor [ʍɔːr], KK hwoer [ʍoːr] ('sister'). This is because evidence suggests the second group of words with o underwent a different phonological development to the first group with oe.[5]

^8 Pronounced solely as [uː] in RLC.

^9 Given as [y] in the original Specification[2] but as [ʏ] in the updated online dictionary.[6] Reduced to [ɪ] when unstressed.[2]

^10 Reduced to [ɪʊ] when stressed and word-final or before gh. In a small number of words, u can represent [ʊ] when short or [uː] or [ɪʊ] when long in TC and RLC. The 2013 Review recommends these be spelt optionally as ù and û respectively in "dictionaries and teaching materials".[5]

^11 Can be pronounced [ɛ, eː] and therefore spelt e in TC and RLC.

Diphthongs

editLetter RMC TC RLC aw [aʊ] [æʊ]1 ay [aɪ] [əɪ], [ɛː] ei2 - [əɪ] ew [ɛʊ] ey [ɛɪ] [əɪ] iw [iʊ] [ɪʊ] ow [ɔʊ] [ɔʊ], [uː]3 oy [ɔɪ]4 uw [ʏʊ]5 [ɪʊ] yw [ɪʊ] [ɛʊ]6

^1 Loanword spelt with aw are often pronounced [ɒ(ː)] in TC and RLC.

^2 Used as a variant graph by RLC when i is diphthongised to [əɪ] in stressed open syllables.

^3 Used in hiatus.

^4 A few monosyllables may keep the more conservative pronunciation [ʊɪ] in RLC, e.g. moy [mʊɪ] ('more'), oy [ʊɪ] ('egg').

^5 Given as [yʊ] in the original Specification[2] but as [ʏʊ] in the updated online dictionary.[7]

^6 The variant graph ew may be used instead of yw to represent the pronunciation [ɛʊ].

Consonants

editLetter RMC TC RLC b [b] c [s] cch [tʃː] [tʃ] ch [tʃ] ck1 [kː], [k] [k] cy2 [sj] [ʃ(j)] d [d] dh [ð] [ð], [θ]3 [ð] f [f] [f], [v]4 ff [fː] [f] g [ɡ] gh [x] [h] ggh [xː] [h] h [h] hw [ʍ] j [dʒ] k [k] kk [kː] [k] ks [ks], [gz] l [l] ll [lː] [lʰ], [l] [lʰ] m [m] mm [mː] [m] [ᵇm]5 n [n] nn [nː] [nʰ], [n] [ᵈn]5 p [p] pp [pː] [p] r [r] [ɹ] [ɹ],[ɾ] rr [rː] [ɾʰ], [ɹ] [ɾʰ] s [s], [z]6 sh [ʃ] ss [sː], [s] [s] ssh [ʃː] [ʃ] t [t] th [θ] tt [tː] [t] tth [θː] [θ] v [v] [v], [f]3 [v] w [w] y [j] z [z]

^1 Used solely in words whose status as borrowings is in no doubt.

^2 In certain borrowed words, such as fondacyon RMC [fɔnˈdasjɔn], RLC [fənˈdæʃjɐn] ('foundation').

^3 TC speakers realise dh as [θ] and v as [f] word-finally in an unstressed syllable. RLC speakers may not even realise these sounds at all, although this is reflected in spelling, e.g. TC menedh [ˈmɛnɐθ], RLC mena [ˈmɛnɐ] ('mountain').

^4 [v] often occurs morpheme-initially before vowels. The mutation of [f] to [v] found in some varieties of Cornish is not shown in writing.

^5 A few words spelt with mm and nn lack pre-occlusion in RLC. These include words thought to have entered the language after pre-occlusion occurred, e.g. gramm ('gramme'), and words that fell out of use by the RLC period, e.g. gonn ('I know').

^6 The distribution of [s] and [z] differs in each variety of Cornish. Some rules are common to almost all speakers, e.g. final s and medial s between vowels or a sonorant and a vowel are usually [z], whereas other rules are specific to certain varieties, e.g. RMC speakers usually realise initial s as [s] whereas RLC tend to prefer [z] (except in such clusters as sk, sl, sn, sp and st). The mutation of [s] to [z] found in some varieties of Cornish is not shown in writing.

My Chinese name: Rèn Yèniǎo 任晔鸟

edit| Éanna Brennan's (draft) name in Chinese | |||||||

| Pinyin | Simplified | Traditional | "Meaning" | ||||

| Rèn Yèniǎo | 任晔鸟 | 任曄鳥 | duty bright bird | ||||

| Comment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 任 Rèn is a surname chosen for its similarity to the first sound in Brennan.

任 means 'trust, duty, allow' and contains the 亻 form of the 'person' radical 人 rén, and the 'load on a carrying pole(?)' character 壬 rén. 晔鸟 Yèniǎo as a given name can represent the Irish name Éanna ['e:nə]. 曄 (Simplified 晔) yè is 'bright'. Its radical is 日 rì 'sun', and its other element is the 'illustrious' character 華 huá (itself made of the 'grass' radical 艹 cǎo and the 'basket' radical 𠦒 bān). 鳥 (Simplified 鸟) niǎo 'bird' and derives from an Oracle Bone script pictogram of a bird. The bird-radical is an echo of Old Irish énna 'birdlike'. | |||||||

| Readings of Éanna Brennan's name in Han characters | |||||||

| Tang | Mandarin | Cantonese | Taiwanese | ||||

| * Njim _ *Děu | Rèn Yèniǎo | Jam6 Jip6-niu5 | Jīm[?] _-niáu | ||||

| Hakka | Korean | Vietnamese | Japanese | ||||

| _ _-niâu | Im Yeopjo (임엽조) | Nhậm Diệp Điểu[?] | Nin Yō Chō | ||||

- ^ Jenner, H. (1915/6) "The fourteenth century endorsement", in: Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall; vol. 20

- ^ a b c d e f Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Cornish Dictionary "lowen"". Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ "eur". Cornish Dictionary. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d "SWF Review Report". Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ "Cornish Dictionary "durya"". Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ "Cornish Dictionary "pluwek"". Retrieved 27 August 2014.