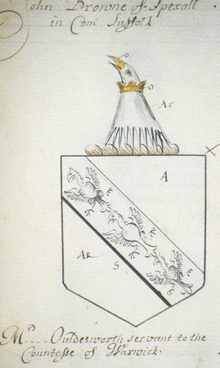

Tricking is a method for indicating the tinctures (colours) used in a coat of arms by means of text abbreviations written directly on the illustration. Tricking and hatching are the two primary methods employed in the system of heraldry to show colour in black and white illustrations.

Origin edit

Heraldry has always had some methods to designate the tinctures of arms. The earliest such method was blazon, which is describing the arms by words. The earliest surviving blazon is from the work of Chrétien de Troyes from the late 12th century.[2] The English heraldry system still uses a form of blazon almost unchanged since the reign of Edward I.

Traditionally, images in heraldic manuscripts such as rolls of arms and armorials are all coloured. With the spread of the printing press, woodblock printing and copperplate engravings from the late 15th century, there arose the need for designating the colours in uncoloured illustrations as well, since printing in full colour was too labour- and cost-intensive. As a rule, two main methods were applied to achieve this – tricking, or giving designations to the tinctures after the initials of the given colours; and hatching, which is ascribing designations to the tinctures by means of lines and dots. While the first method was introduced and developed by the heralds, the second model was developed and adopted by the heraldists.[citation needed] In addition, some other methods were also in use such as giving designations to tinctures by using the numbers from 1 to 7.[citation needed]

Until the 16th century, heraldic sources designated tinctures with the regular names of the colours.[3] By the middle of the century, heraldic writers started using the initials of the tinctures after the initials of the given colours.[4] Almost simultaneously, Don Alphonsus [Francisco] Ciacconius, a Rome-based Spanish Dominican scholar, named the tinctures after their Latin initials.[citation needed] Or was designated with "A", for aurum; argent with "a" for argentum; azure with "c" for caeruleus; gules with "r" for rubeus; and vert by "v" for viridis. Though the sign for sable (niger in Latin) was not present in his system, traditionally it was designated with the black colour itself.

Decline edit

From the early 17th century, tricking declined. However, it is sometimes still in use, mainly in British heraldry.

Heralds did not like hatching, since tricking was much easier to write and engrave. The College of Arms gave preference to tricking even beyond the 17th century, sometimes even on the coloured and hatched images. However, tricking's letters were often traced badly since they were not always immediately understood, thus leading to erroneous interpretations.

Otto Titan von Hefner, a 19th-century German herald, maintained that the first traces of hatching on the woodcuts began during the 15th and 16th centuries. Both tricking as well as hatching were applied by Vincenzo Borghini, a Benedictine monk, philologist and outstanding historian. He drew a difference between the metals and the colours on the woodcuts of his work by leaving the places blank on the arms for all metals; similarly all colours were hatched by the same way, as the colour vert is being used today. Besides this, tinctures were designated in the fields and on the ordinaries and charges by tricking: R–rosso–gules, A–azure–azure, N–nigro–sable, G–gialbo–yellow (Or), and B–biancho–white (argent). Notably, vert was not present on the arms presented by him.

References edit

- ^ Ciacconius, Alphonsus (1677). Vitae et res gestae Pontificum romanorum et S.R.E.Cardinalium: ab initio nascentis Ecclesiae vsque ad Clementem IX P.O.M. [Life and achievements of the Roman Pontiffs and the HRC Cardinals: from the beginnings until Clement IX] (in Latin). Vol. 3. Philippi et Ant. De Rubeis. Column 65, XIX.

- ^ Chrétien de Troyes, Lancelot ou le Chevalier de la charrette, c.1178–c.1181[full citation needed]

- ^ Martin Schrot, Wappenbuch, 1576[full citation needed]

- ^ Cristian Urstis, Baselische Chronik , (1580)[full citation needed]; Virgil Solis, Wappenbüchlein, 1555[full citation needed]; Johann von Francolin (1560)[full citation needed]