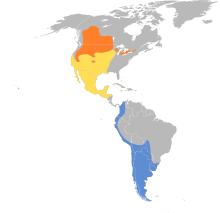

Wilson's phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) is a small wader. This bird, the largest of the phalaropes, breeds in the prairies of North America in western Canada and the western United States. It is migratory, wintering in inland salt lakes near the Andes in Argentina.[2] They are passage migrants through Central America around March/April and again during September/October.[3] The species is a rare vagrant to western Europe.

| Wilson's phalarope | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female (breeding plumage) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Phalaropus |

| Species: | P. tricolor

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phalaropus tricolor (Vieillot, 1819)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Steganopus tricolor | |

This species is often very tame and approachable. Sometimes it is placed in a monotypic genus Steganopus.

Etymology

editThis bird is named after Scottish-American ornithologist Alexander Wilson.[4] The English and genus names for phalaropes come through French phalarope and scientific Latin Phalaropus from Ancient Greek phalaris, "coot", and pous, "foot". Coots and phalaropes both have lobed toes. The specific tricolor is from Latin tri-, "three-", and color, coloris "colour".[5][6]

Description

editWilson's phalarope is slightly larger than the red phalarope at about 23 cm (9.1 in) in length. It is a dainty shorebird with lobed toes and a straight fine black bill. The breeding female is predominantly gray and brown above, with white underparts, a reddish neck and reddish flank patches. The breeding male is a duller version of the female, with a brown back, and the reddish patches reduced or absent.

Measurements:[7]

- Length: 8.7–9.4 in (22–24 cm)

- Weight: 1.3–3.9 oz (37–111 g)

- Wingspan: 15.3–16.9 in (39–43 cm)

In a study of breeding phalaropes in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada, females were found to average around 10% larger in standard measurements and to weigh around 30% more than the males. Females weighed from 68 to 79 g (2.4 to 2.8 oz), whereas males average 51.8 g (1.83 oz).[8]

Young birds are grey and brown above, with whitish underparts and a dark patch through the eye. In winter, the plumage is essentially grey above and white below, but the dark eyepatch is always present. The average longevity in the wild is 10 years.[9]

Ecology and status

editWilson's phalaropes are unusually halophilic (salt-loving) and feed in great numbers when on migration on saline lakes such as Mono Lake in California, Lake Abert in Oregon, and the Great Salt Lake of Utah, often with red-necked phalaropes.

When feeding, a Wilson's phalarope will often swim in a small, rapid circle, forming a small whirlpool. This behaviour is thought to aid feeding by raising food from the bottom of shallow water. The bird will reach into the outskirts of the vortex with its bill, plucking small insects or crustaceans caught up therein.

The typical avian sex roles are reversed in the three phalarope species. Females are larger and more brightly coloured than males. The females pursue males, compete for nesting territory, and will aggressively defend their nests and chosen mates. Once the females lay their eggs, they begin their southward migration, leaving the males to incubate the eggs. Three to four eggs are laid in a ground nest near water. The young feed themselves.

Although very common, this bird's population may have declined in some areas due to the loss of prairie wetland habitat. A few staging areas are of critical importance during migration.

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Steganopus tricolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22693472A93409634. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693472A93409634.en. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "500,000 birds to migrate from Utah to Argentina". The Advocate. August 4, 2013.

- ^ Herrera, Néstor; Rivera, Roberto; Ibarra Portillo; Ricardo & Rodríguez, Wilfredo (2006). "Nuevos registros para la avifauna de El Salvador" [New records for the avifauna of El Salvador] (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Antioqueña de Ornitología (in Spanish and English). 16 (2): 1–19.

- ^ Szabo, M.J. (2013) Wilson's phalarope in Miskelly, C.M. (ed.) New Zealand Birds Online.

- ^ "Phalarope". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 301, 390. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Wilson's Phalarope Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ Colwell, Mark A.; Oring, Lewis W. (October 1988). "Breeding Biology of Wilson's Phalarope in Southcentral Saskatchewan" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 100 (4): 567–582.

- ^ Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

Further reading

edit- Hayman, Peter; Marchant, John & Prater, Tony (1986): Shorebirds: an identification guide to the waders of the world. Houghton Mifflin, Boston. ISBN 0-395-60237-8

External links

edit- Wilson's phalarope – Phalaropus tricolor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Wilson's phalarope photos at Oiseaux.net

- Wilson's phalarope photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- "Phalaropus tricolor". Avibase.

- "Wilson's phalarope media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Interactive range map of Phalaropus tricolor at IUCN Red List maps