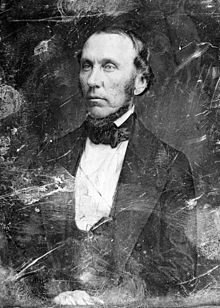

Solomon Weathersbee Downs (1801 – August 14, 1854) was an American attorney, politician, and slaveholder from Louisiana. A Democrat, he served as a United States senator from 1847 to 1853.

Solomon Weathersbee Downs | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Louisiana | |

| In office March 4, 1847 – March 3, 1853 | |

| Preceded by | Pierre Soulé |

| Succeeded by | Judah P. Benjamin |

| United States Collector of Customs for the District of Orleans | |

| In office April 6, 1853 – August 14, 1854 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | George C. Laurason |

| Succeeded by | Thomas C. Porter |

| United States Attorney for the District of Louisiana | |

| In office April 26, 1845 – June 14, 1846 | |

| President | James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | Balie Peyton |

| Succeeded by | Thomas J. Durant |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1801 Montgomery County, Tennessee, US |

| Died | August 14, 1854 (aged 52–53) Lincoln County, Kentucky, US |

| Resting place | Riverview Cemetery, Monroe, Louisiana, US |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Ann Marie McCaleb |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Transylvania University |

| Profession | Attorney |

The village of Downsville, Louisiana is named for him.[1][2]

Early life

editDowns was born in Montgomery County, Tennessee, in 1801,[3] the illegitimate son of William Weathersbee and Rebecca Downs.[4] His family later moved to Louisiana, and sent Downs back to Tennessee to study under Thomas B. Craighead.[5] He then attended Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, from which he graduated in 1823.[5] He studied law, was admitted to the bar in 1826 and commenced practice in Bayou Sara, Louisiana.[6] He later moved to Ouachita, where he practiced law and owned and operated a plantation.

Downs enslaved dozens of African Americans on his two Ouachita Parish plantations. In the 1850 slave schedules, he is listed as holding a total of 154 men, women, and children in bondage.[7][8]

Career

editA Democrat, he became active in politics as a campaign speaker on behalf of Andrew Jackson in 1828.[5] In 1838, he won election to the Louisiana State Senate from Catahoula, Ouachita and Union Parishes, and he was reelected in 1842.[9][10]

A longtime member of the Louisiana Militia, in 1842 Downs was appointed brigadier general of the organization's 6th Division.[11]

In 1844 he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention.[12] Also in 1844, he agreed to run for presidential elector as a supporter of Martin Van Buren.[13] When Van Buren came out against annexing Texas, Downs resigned, but he agreed to run again after James K. Polk was nominated.[13] Polk won the election and carried Louisiana, and Downs cast his ballot for the ticket of Polk for president and George M. Dallas for vice president.[13]

Downs moved to New Orleans in 1845. He served as United States Attorney for the district of Louisiana from 1845 to 1846 and a member of the State constitutional convention.

He was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate and served from March 4, 1847, to March 3, 1853. While in the Senate he was chairman of the Committee on Engrossed Bills (Thirtieth Congress) and the Committee on Private Land Claims (Thirtieth through Thirty-second Congresses).[13]

In the Senate, Downs was an unusually staunch supporter of the institution of slavery, from which he personally profited. "I call upon the opponents of Slavery to prove that the white laborers of the North are as happy, as contented, or as comfortable as the slaves of the South," he said in one speech. "In the South the slaves do not suffer one tenth of the evils endured by the white laborers of the North...This, sir, is one of the excellencies of the system of Slavery, and this the superior condition of the Southern slave over the Northern white laborer."[14]

After his term, he was appointed by President Franklin Pierce as United States Collector of Customs for the District of Orleans in 1853 and he served until his death.[15]

Death and burial

editDowns died in Crab Orchard Springs, Kentucky on August 14, 1854,[16] and was buried on his family's plantation in Kentucky.[17] He was later reburied at Riverview Sanitarium in Monroe, Louisiana, and the burial ground there became Riverview Cemetery.[17] Under the terms of his will, Downs freed a slave, Richard Barrington, who had been taught to read and write while living on Downs' plantation.[18] Barrington later became a successful barber in New Orleans, and learned that Downs' grave had not been marked, so Barrington paid for a headstone.[18] Downs' grave was later lost, and was uncovered again in 1937.[18] After being moved to a spot near the cemetery entrance, the grave was forgotten about a second time.[18] It was rediscovered in 2000, and is marked by the broken pieces of the headstone originally purchased by Barrington.[18]

Family

editIn 1830, Downs married Ann Marie McCaleb (d. 1857).[19] They were the parents of two children, Samuel Alfred Downs and Sarah Mary Downs.[19]

References

edit- ^ "The Strange History of Senator Downs". Bryan Park: Gateway to Green Living. 6 July 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Breard, Sylvester (17 November 2011). Early History of Monroe. Pelican Publishing Company, Inc. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4556-1689-3.

- ^ Louisianan, A. (Pen name) (1852). Biography of the Hon. Solomon W. Downs. Washington, DC: Robert Armstrong. p. 4 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Gilley, B. H. (1984) [1902]. North Louisiana: To 1865. Ruston, LA: Louisiana Tech University, McGinty Trust Fund Publications. p. 13. ISBN 9780940231030 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Biography, p. 4.

- ^ Biography, p. 4.

- ^ "United States Census (Slave Schedule), 1850". Retrieved 23 March 2023 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ Weil, Julie Zauzmer (10 January 2022). "More than 1,800 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation". Washington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2024. Database at "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, 2022-01-13, retrieved 2024-04-29

- ^ Biography, p. 5.

- ^ "Re-Election of S. W. Downs". Morning Advertiser. New Orleans, LA. July 14, 1842. p. 2 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- ^ "The Following Gentlemen Were Elected by the Legislature in Joint Ballot". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans, LA. March 26, 1842. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Biography, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Biography, p. 13.

- ^ Society, American Abolition (1857). The Kansas Struggle, of 1856, in Congress, and in the Presidential Campaign: With Suggestions for the Future. American Abolition Society.

- ^

- United States Congress. "Solomon W. Downs (id: D000476)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ "Death Notice, Gen. S. W. Downes". The Buffalo Commercial. Buffalo, NY. August 17, 1854. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Hardin Urges that Long Lost Grave of Solomon Downs, Great Louisiana Statesman, Be Marked". Shreveport Journal. Shreveport, LA. February 25, 1937. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Reed, Jennifer (July 6, 2009). "The Strange History of Senator Downs". Bryan Park: Gateway to Green Living. Downsville, LA: Village of Downsville.

- ^ a b Headley, Katy McCaleb (1964). MacKillop (McCaleb) Clan of Scotland and the United States. Vol. I. Chillicothe, MO: Elizabeth Prather Ellsberry. p. 158 – via Internet Archive.

External links

edit- United States Congress. "Solomon W. Downs (id: D000476)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.