The sekhem scepter is a type of ritual scepter in ancient Egypt. As a symbol of authority, it is often incorporated in names and words associated with power and control. The sekhem scepter (symbolizing "the powerful") is related to the kherp (ḫrp) scepter (symbolizing "the controller") and the aba scepter (symbolizing "the commander"), which are all represented with the same hieroglyphic symbol.[1] These scepters resembled a flat paddle on a papyrus umbel handle. Its symbolic role may have originated in Abydos as a fetish of Osiris. The shape of the scepter might have derived from professional tools.

| ||

| aba, (kh)rp, or sekhem scepter in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

Symbol of rank

editBeing a symbol of power or might, the sekhem was frequently incorporated into various names. For example, that of the Third Dynasty Pharaoh Sekhemkhet, and the lioness-goddess Sekhmet, whose name means "she who is powerful".

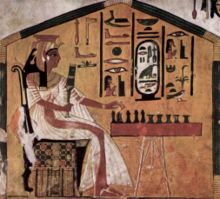

After the Third Dynasty, the sekhem appeared in the royal names of the pharaohs, and later in the titles of queens and princesses as well. When the king held a sekhem scepter in his right hand, he would usually hold a mace or censer in the left.

From the earliest times, viziers and other officials of important rank held the sekhem, symbolizing the individual's successful life and prestigious position. Such officials were often portrayed holding the scepter in the course of performing their duties. If they held the scepter in their right hand, they would usually hold a staff in the left hand. The classic Egyptian funerary statue depicted the deceased with a staff in one hand, and the sekhem in the other. As a scepter of office, a pair of eyes were carved on the upper part of the staff.

Sekhem, meaning "power"

edit

| ||||||

| sḫm "Power" (of Harp-(music)) (procession) in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Egyptian language word sḫm is the word for power. A procession of a woman with a bouquet of flowers, followed by a harpist, from Medamud illustrates the use of the word: "...(from) the gods, Power (of the) Harp-Music..."

Sekhem, meaning "form"

editThe word sekhem, which means "form", is also a part of the Ancient Egyptian concept of the soul or spirit.

Religious symbolism

editOsiris was often called the Great Sekhem or Foremost of Powers. Hence, the sekhem was often used as a symbol of the underworld deity. This practice probably led to the scepter also becoming an emblem of Anubis. The sekhem scepter was sacred to Anubis in the temple of Hu (known as the "Enclosure of the Sekhem" (ḥwt-sḫm)). Anubis is frequently depicted in his manifestation of a reclining dog with a sekhem scepter behind him. In such depictions, the scepter is often portrayed with an elongated head. The scepter was also associated with Khentiamentiu (Chief of the Westerners), another deity who was especially associated with the royal cemetery. In this type of iconographic representation, the sekhem is often given two eyes, which were carved or painted on the scepter's upper part as a symbol indicating that it was the manifestation of divine power.

The sekhem was also utilized in temple and mortuary offering rituals. The officiant who presented offerings often held it. In such cases, the scepter was held in the right hand and was waved four or five times over the offerings while ritual recitations were made. A gilded sekhem scepter was found in Tutankhamun's tomb. On the back of this scepter were carved five registers depicting a slaughtered bull, which may indicate that the scepter was waved five times over the offering. When consecrating offerings, the king used two sekhem scepters: one for Set and another for Horus. Elsewhere, Horus and Seth appear as "the Two Sekhems" (sḫmwy).

A late variant of this type of scepter hieroglyph sometimes represented the sistrum,[1] a musical rattle that was sacred to Hathor and carried by her priestesses. The sistrum had a metal loop with jingles mounted on a cow-goddess faced handle.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Gardiner, Alan Henderson (1957). Egyptian grammar: being an introduction to the study of hieroglyphs. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum. p. 509. ISBN 978-0-900416-35-4.