René Kalisky (French: [ʁəne kaliski]; born Kaliski, Polish: [kaˈliskʲi]; 20 July 1936 – 6 May 1981) was a Belgian writer of Polish-Jewish descent who is best known for the plays he wrote in the last 12 years of his life. Kalisky, whose father, Abraham Kaliski was killed at Auschwitz, was himself hidden from harm during World War II.

René Kalisky | |

|---|---|

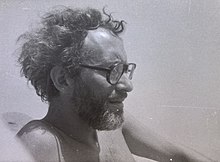

Kalisky in 1965 | |

| Born | René Kaliski 20 July 1936 Etterbeek, Belgium |

| Died | 6 May 1981 (aged 44) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Paris, France |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Surtexte/[1] supertext[2] |

| Notable work | Falsch |

| Spouse | |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Personal life

editKalisky was born in Etterbeek, one of municipalities located in the Brussels-Capital Region of Belgium, 20 July 1936. His father Abram Kaliski was born in Łódź on 10 May 1908. His grandparents, Solomon Yitzhak Kaliski and Hadassah Kaliski, had at least 8 children, who all perished during the Holocaust except for one son and one daughter. After his wife's death, fleeing the pogroms, Solomon traveled to South Africa before ending up in Mandatory Palestine at the beginning of the century and died in Tel-Aviv in 1948, aged 80.

Abram emigrated to Belgium where he became a leather merchant and a dancer. Aged 23, in 1932, he met and married Fradla Wach, born in Warsaw on November 15, 1901. They had four children: René who became a writer, Haim who became a historian, cartoonist and author, Sarah who became a painter and Ida. All of the four children were dispatched and remained hidden in separate places during the war. Their parents stayed alone and survived almost until the surrender of the Nazi German forces. Abram nevertheless was caught by the Belgian police while seeking milk for their newborn. After being imprisoned and tortured in the Mechelen transit camp, he reportedly was assassinated in Auschwitz around December 1944, being 36 years old. Fradla gathered her four kids and raised them alone after the war ended. Kalisky was about eight years old when he lost his father. Although their mother was illiterate, he recalled his parents always wished their children could become accomplished artists.[citation needed]

Career

editHe began his career in the field of publishing as a secretary and, in the field of journalism, notably the Patriot Illustré, before taking the path to theater. In 1968, he began with the publication of Europa, in Belgium. Kalisky wrote several historical pieces including Trotsky (1969), Skandalon (1970), Jim le Téméraire and Le Pique-Nique de Claretta (1973). He also authored two major essays published in 1968 and reissued in the 1980s on Arab political history, L’origine et l’essor du monde arabe and Le monde arabe à l'heure actuelle: Le réveil et la quête de l’unité. He worked with Jacques Lemarchand, director of the established collection "Le Manteau d’Arlequin", at Gallimard in France until 1974.

His career slowly began to flourish as he received several literary prizes, including the Annual Dramatic Literature Prize awarded by the Society of Dramatic Authors and Composers in 1974 and the Triennial Grand Prize for Dramatic Literature awarded by the Government in 1975. He then was awarded by Germany and asked to craft an original project across a yearlong stay in former western Berlin. In 1977, the French editor, Stock published several controversial pieces, including, “La passion selon Pier Paolo Pasolini”, “Dave au bord de mer”, “Résumé” and “Du sur jeu au sur texte” in which he describes us his own and personal vision of his theater work.

His last pieces were mostly directed by French theatrical companies, "Sur les ruines de Carthage" (1980). Several theater and film directors expressed an increasing interest in Kalisky and brought his works to the stage, including Antoine Vitez, Albert-André Lheureux, Ewa Lewinson, Bernard de Coster, Jean- Pierre Miquel, or Marcel Delval. Since 1974, Kalisky's plays have been played and replayed on the most National stages, such as Le Botanique Garden Theater in Brussels, the Théâtre National de l'Odéon, at the Comédie Francaise, the Théâtre de l'Est Parisien, or Théâtre National de Chaillot and the Festival d’Avignon.

He abruptly died of lung cancer aged 44. Among his friends and contemporary authors, Romain Gary shared a special relationship with Kalisky, as he viewed them, as recalled by their published correspondence.[3] An abundant published correspondence with Antoine Vitez likewise showed how close they had become.[4]

Falsch, his last play, was then created in 1983 by Antoine Vitez in Paris, Théâtre National de Chaillot,[5] and later on adapted by the Dardenne brothers into a movie that was screened in 1987, starring Bruno Cremer.[6][7]

Awards and recognition

edit- 1974, the annual Dramatic Literature Prize, awarded by the Society of Dramatic Authors and Composers SACD.

- 1975, the Triennial Grand Prize for Dramatic Literature, awarded by the Government.

- 1982, Special Prize, posthumously awarded by the Society of Dramatic Authors and Composers SACD.

- 1987, Best Foreign Play Prize awarded by the German Theater Heute

- 2004, Aïda vaincue, Theater Critics Award for best play, best actor for Julien Roy, best actress for Jo Deseure, best scenography for Philippe Henry

Works

edit- Falsch, his last play, (1980), Éditions Labor was published posthumoustly, 1983

- Du Surjeu au surtexte, in Dave au Bord de Mer, Paris, L'Arche, 1992, pp. 91–109

- L’origine et l’essor du monde arabe : L’essor et le déclin d’un empire, (1968), (1980), Marabout-Université Full text available on the Bibliothèque Nationale Website

- Le monde arabe à l'heure actuelle: Le réveil et la quête de l’unité, (1974), Marabout-Université

- Le pique-nique de Claretta, (1973), NRF, Gallimard, and France Culture, Directed by Michel Dezoteux, PRIX TRIENNAL DE THÉÂTRE DU MINISTRE DE LA CULTURE FRANÇAISE 1975.

- Sionisme ou dispersion, (1974), Marabout-Université

- Charles le téméraire, (1975), Éd. Jacques Antoine

- Le tiercé de Jack<, (1975), Scenario

- Europa, (1968), Alternatives théâtrales 1995, Directed by Marc Olinger

- L’impossible royaume, (1979), Seghers

- Trotsky, etc..., (1969), NRF, Gallimard

- Skandalon, (1970), NRF, Gallimard directed by Memè Perlini in 1989[8]

- Jim le téméraire, (1973), NRF, Gallimard

- Le Pique-Nique de Claretta, (1973), NRF, Gallimard first directed by Antoine Vitez at the Théâtre d'Ivry Antoine Vitez in 1974[9]

- La Passion selon Pier Paolo Pasolini, (1977), Stock Directed by Albert-André Lheureux, Théâtre National de Chaillot

- Dave au bord de mer, (1977), Stock, L'Arche first directed by Antoine Vitez in 1979 with actors Richard Berry, Claude Mathieu,[10] Bérengère Dautun,[11] Patrice Kerbrat,[12] Jean Le Poulain[13] at the Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe of the Comédie-Française in Paris, and then Directed by Jules-Henri Marchant 1993

- Aïda vaincue L'Arche Foreword by Jacques De Decker, directed by Antoine Vitez at the Comédie-Française marking his return to Kalisky's art[14] at the Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe: he died about a month before the rehearsals. He was replaced by Patrice Kerbrat[12] and the Comedians de La Troupe de la Comédie-Française,[15] Claude Mathieu,[10] Alberte Aveline,[16] Jean-Yves Dubois,[17] Dominique Constanza[18] who played Aïda, Éric Frey, with a scenography of Yannis Kokkos[19]

- Sur les ruines de Carthage, (1980), Éditions Labor Directed by Michel Delaunoy

Movies

edit- "Falsch" adapted in (1987) by Jean-Pierre Dardenne and Luc Dardenne featuring Bruno Cremer, Bérengère Dautun, Christian Crahay and Jacqueline Bollen[20][7]

- "Le tiercé de Jack" adapted in (1975) by Jean-Pierre Berckmans telling the story of Jack, sixteen, a young Jew, who saw his father arrested by the Nazis. He had to hide himself to escape deportation, to death. He lives with his mother in the obsession of this tragic past. Everywhere, in the street, at the leather shop where he works, he continues to feel a different being, frowned upon, persecuted.

- "Skandalon" adapted in (1972) by Dries Wiemes starring Chris Lomme and Gerard Vermeersch

Surtexte, supertext or superacting

editThe "surtexte" technique that he forged along his short career has been studied by numerous directors and authors as defined by Encyclopedia Universalis.[1] That new concept could be related to "Brecht's "distancing effect" ("Verfremdungseffekt"), which aims to break the theatrical illusion to awaken the critical sense of the audience by giving it to see the artificial nature of representation, and thus making everyone aware of his position as a spectator"[21]

Bibliography

edit- Serge Goriely, Le théâtre de René Kalisky, Brussels, PIE Peter Lang, 2008.

- Gilbert Debuscher, D'Aristote a Kalisky, Brussels, Université de Bruxelles, 2004. Downloadable Full Text

- Agnese Silvestri, René Kalisky, une poétique de la répétition, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2006. 415 p.

- Marc QUAGHEBEUR, Ballet de la déception exaltée : Jim le Téméraire de René Kalisky In: Ecritures de l' imaginaire: dix études sur neuf écrivains belges, Bruxelles, Labor (Archives du futur), 1985, p. 159-211

- Anne-Françoise Benhamou, Kalisky, Vitez et le temps enroulé in L'Art du théâtre, Actes Sud, 1989, Antoine Vitez à Chaillot, pp. 108–110

- Michael Delaunoy, Rêveries à propos de Trotsky, etc... de René Kalisky, L'Harmattan, « Études théâtrales », 2011 Full Text

Translations of his work

edit- Falsch, translated in German by Ruth Henry, Bad Homburg Hunzinger-Bühnenverlag, 1984.

- Jim the Lionhearted, translated in English by David Willinger and Luc Deneulin An Anthology of Recent Belgian Plays, Troy, NY, Whitston Publishing Company, 1984.

- Claretta Picknick, translated in German by Andres Müry, Bad Homburg Hunzinger-Bühnenverlag, 1983.

- Jim der Kühne, translated in German by Andres Müry, Bad Homburg Hunzinger-Bühnenverlag, 1985.

- Dave on the Beach, translated in English by David Willinger and Luc Deneulin, in An Anthology of Recent Belgian Plays, Troy, NY, Whitston Publishing Company, 1984.

- On the Ruins of Carthago, translated in English by Anne Marie Glasheen, in Four Belgian playwrights, Gambli n°42-43, 1986

- Aida Vencida, translated in Spanish by Carmen Giralt, Publicaciones de la Asociación de Directores de Escena de España, 1993.

- Europa, translated in Spanish by Carmen Giralt, Publicaciones de la Asociación de Directores de Escena de España, 1993.

- Skandalon translated in Italian by Brunella Eruli, Gremese Editore, 2007.

- Jim il Temerario translated in Italian by Brunella Eruli, Gremese Editore, 2007.

- Il picnic di Claretta, translated in Italian by Brunella Eruli, Gremese Editore, 2007.

- La Passione secondo Pier Paolo Pasolini, translated in Italian by Brunella Eruli, Teatro Belgo contemporaneo, Gênes, Coste el Nolan, 1984.

- Europa, translated in Italian by Brunella Eruli, Gremese Editore, 2007.

- Sulle rovine di Cartagine, translated in Italian by Brunella Eruli, Gremese Editore, 2007.

- Pasja według Piera Paola Pasoliniego, translated in Polish by Kuchta, Barbara Mickiewicz-Morawska, Dorota.

- Il regno impossibile, translated in Italian by Brunella Piccione, Omnia Editrice, 1986.

- Het onmogelijke koninkrijk, translated in Dutch by Ton Luyben, Anvers, Manteau, 1987.

- Storia del mondo arabo, translated in Italian, Bertani, 1972

References

edit- ^ a b Universalis, Encyclopædia. "Définition de surtexte – Encyclopædia Universalis". www.universalis.fr.

- ^ "René Kalisky – Belgian author".

- ^ [Correspondance : Lettres de [Romain Gary] à [René Kalisky] (1972–1980)]

- ^ "MORT DE RENÉ KALISKY Comme un écolier". Le Monde.fr. 15 May 1981.

- ^ Gershman, Judith (21 September 1983). "Falsch by René Kalisky (review)". Performing Arts Journal. 7 (3): 84–85. doi:10.2307/3245153. JSTOR 3245153.

- ^ "Falsch". IMDb.

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: IMAJ - Rencontre : Luc Dardenne - "Falsch" de Jean-Pierre et Luc Dardenne (2005). YouTube.

- ^ "STORIA DI COPPI, CAMPIONE DI GHIACCIO – la Repubblica.it". 6 May 1989.

- ^ "VITEZ: 'VEDIAMO UN PO' COM' ERA IL TEATRO DELLA RIVOLUZIONE...' – la Repubblica.it". 15 April 1989.

- ^ a b Agency, Hands. "Claude Mathieu".

- ^ Agency, Hands. "Bérengère Dautun".

- ^ a b Agency, Hands. "Patrice Kerbrat".

- ^ Agency, Hands. "Jean Le Poulain".

- ^ Agency, Hands. "Aïda vaincue".

- ^ Agency, Hands. "Comédiens de la Troupe".

- ^ Agency, Hands. "Alberte Aveline".

- ^ Agency, Hands. "Jean-Yves Dubois".

- ^ Agency, Hands. "Dominique Constanza".

- ^ Photographe, Cande, Daniel (1938-....). (21 September 1990). "[Aïda vaincue. Mise en scène de Patrice Kerbrat : photographies / Daniel Cande]". Gallica.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mosley, Philip. 2013. The Cinema of the Dardenne Brothers: Responsible Realism. New York: Wallflower Press. [1]

- ^ Du Surjeu au surtexte» in Dave au Bord de Mer, Paris, L'Arche, 1992, pp. 91-109