Radbod (died 719) was the king (or duke) of Frisia from c. 680 until his death. He is often considered the last independent ruler of Frisia before Frankish domination. He defeated Charles Martel at Cologne. Eventually, Charles prevailed and compelled the Frisians to submit. Radbod died in 719, but for some years his successors struggled against the Frankish power.

| Radbod | |

|---|---|

| King (or Duke) of Frisia | |

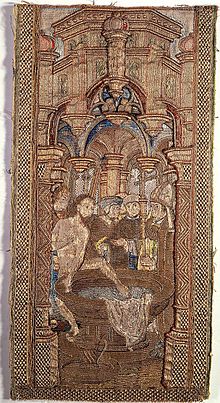

Embroidery depicting the legend in which the Frisian king Radbod is ready to be baptized by Wulfram (in this embroidery replaced by Willibrord), but at the last moment refuses. From the Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht | |

| Reign | c. 680 – 719 |

| Predecessor | Aldgisl |

| Successor | Bubo |

| Born | c. 648 |

| Died | 719 |

| Religion | Germanic paganism |

King or duke

editWhat the exact title of the Frisian rulers was depends on the source. Frankish sources tend to call them dukes; other sources[which?] often call them kings.[citation needed]

Reign

editWhile his predecessor, Aldgisl,[1] had welcomed Christianity into his realm, Radbod attempted to extirpate the religion and gain independence from the kingdom of the Franks. In 689, however, Radbod was defeated by Pepin of Herstal in the battle of Dorestad[2] and compelled to cede Frisia Citerior (Nearer Frisia, from the Scheldt to the Vlie) to the Franks.

Between 690 and 692, Utrecht fell into the hands of Pepin. This gave the Franks control of important trade routes on the Rhine to the North Sea. Some sources say that, following this defeat, Radbod retreated, in 697, to the island of Heligoland. Others say he retreated to the part of the Netherlands that is still known as Friesland.

Around this time there was an Archbishopric or bishopric of the Frisians founded for Willibrord[3] and a marriage was held between Grimoald the Younger, the oldest son of Pepin, and Thiadsvind, the daughter of Radbod in 711.[4]: 794

On Pepin's death in 714, Radbod took the initiative again. He forced Saint Willibrord and his monks to flee and advanced as far as Cologne, where he defeated Charles Martel,[5] Pepin's natural son, in 716. Eventually, however, Charles prevailed and compelled the Frisians to submit. Radbod died in 719,[6]: 90 but for some years his successors struggled against the Frankish power.

As an example of how powerful King Radbod still was at the end of his life, the news that he was engaged in assembling an army was reportedly enough to fill the Frankish kingdom with fear and trembling.[4]: 794

Relation with the Catholic Church

editDuring the second journey of Saint Boniface to Rome, Wulfram, a monk and ex-archbishop of Sens, tried to convert Radbod, but after an unsuccessful attempt he returned to Fontenelle. It is said that Radbod was nearly baptised but refused when he was told that he would not be able to find any of his ancestors in Heaven after his death. He said he preferred spending eternity in Hell with his pagan ancestors than in Heaven with a pack of beggars.[7] This legend is also told with Wulfram being replaced with bishop Willibrord.

Legacy

editSaint Radboud was a descendant of Radbod. Saint Radboud was a bishop of Utrecht who adopted his ancestor's native name. The Nijmegen University and its corresponding medical facility were named after him in 2004.

In Richard Wagner's Lohengrin a certain "Radbod, ruler of the Frisians" is mentioned as Ortrud's ancestor.

In Harry Harrison's The Hammer and the Cross series of novels, Radbod becomes the founder of "the Way", an organized pagan cult, created to combat the efforts of Christian missionaries.

Black metal band Ophidian Forest recorded a concept album Redbad[8] in 2007.

Dutch folk metal band 'Heidevolk' recorded a song 'Koning Radboud' (King Radbod) on their 2008 album 'Walhalla Wacht' singing about the legend of Wulfram and Radbod.

In 2015 the Frisian Folk-Metal band Baldrs Draumar[9] released a full album on the life and deeds of king Redbad called Aldgillissoan.[10] It is based on the book Rêdbâd, Kronyk fan in Kening[11] (Chronicles of a King) by Willem Schoorstra.

In 2018, Dutch production company Farmhouse released a film, Redbad, based on Radbod. It is directed by Roel Reiné and stars Jonathan Banks and Søren Malling alongside a variety of Dutch actors.[12]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ TeBrake, William H. (1978). "Ecology and Economy in Early Medieval Frisia". Viator. 9: 1–30. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301538. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ^ Blok, Dirk P. (1968). De Franken : hun optreden in het licht der historie. Fibulareeks (in Dutch). Vol. 22. Bussum: Fibula-Van Dishoeck. pp. 32–34. OCLC 622919217. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

- ^ it Liber Pontificalis (Corpus XXXVI 1, side 168) en Beda Venerabilis (Corpus XLVI9, page 218)

- ^ a b Halbertsma, Herrius (1982). "Summary" (PDF). Frieslands Oudheid (Thesis) (in Dutch and English). Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. pp. 791–798. OCLC 746889526.

- ^ "Geschiedenis van het volk der Friezen". boudicca.de (in Dutch). 2003. Archived from the original on 2009-06-08. Retrieved 2009-01-22.[self-published source]

- ^ Halbertsma, Herrius (2000). Frieslands oudheid: het rijk van de Friese koningen, opkomst en ondergang (in Dutch and English) (New ed.). Utrecht: Matrijs. ISBN 9789053451670.

- ^ Friese sagen & Terugkeer (2000), Conserve, Uitgeverij, Redbald en Wulfram. ISBN 978-90-5429-138-1

- ^ "Redbad". metal-archives.com. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ^ "Baldrs Draumar". baldrsdraumar.com/.

- ^ "Aldgillessoan". soundcloud.com/.

- ^ "Rêdbâd, Kronyk fan in Kening". bol.com/.

- ^ "754 A.D. REDBAD (2018)". incrediblefilm.com/.

Other sources

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Frisians". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 234–235.

- Petz, G. H. (ed). MGH Scriptures. (Hanover, 1892).

External links

edit- Media related to Redbad, King of the Frisians at Wikimedia Commons