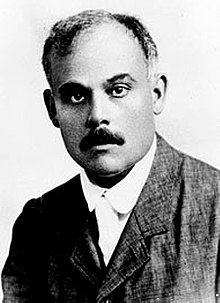

Oszkár Jászi (born Oszkár Jakubovits; 2 March 1875 – 13 February 1957), also known in English as Oscar Jászi, was a Hungarian social scientist, historian, and politician.

Oszkár Jászi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister for National Minorities | |

| In office 31 October 1918 – 19 January 1919 | |

| Preceded by | position created |

| Succeeded by | Dénes Berinkey |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 March 1875 Nagykároly, Austria-Hungary (today Carei, Romania) |

| Died | 13 February 1957 (aged 81) Oberlin, Ohio, United States |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Political party | Civic Radical Party (PRP) |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Lesznai (1913–1918) Recha Wohlmann (1924–?) |

| Children | Andrew Jaszi |

| Parent(s) | Ferenc Jászi Róza Liebermann |

| Profession | sociologist, politician |

Early life edit

Oszkár Jászi was born in Nagykároly on March 2, 1875. His hometown was, as he put it in his unfinished memoirs, "the county seat of Szatmár, the center of a rich agricultural area, it was a major factor in Hungary's economic, municipal and political life."[1] His father, Ferenc Jászi (1838–1910), was a family physician and (in his son's words) "an honorable, humane freethinker" who had had his family name changed from Jakobuvits to Jászi in 1881, a "typical symptom of the very strong and seemingly unqualified drive for assimilation that he and many Jewish contemporaries displayed around that time... This was the family climate that gave rise in the then six-year-old Oszkár to a self-image whereby for a long time thereafter he was simply unwilling to acknowledge his Jewish origins."[2] The family also converted to Calvinism in the same year 1881.

Oszkár's mother, Roza Liebermann (1853–1931), was the widowed doctor's second wife. Oszkár attended "the local Piarist grammar school—the same establishment attended by Endre Ady, two years younger and later to become the supreme poet of their generation (though the two became friends, this dated from their adult years)."[3] Having done very well academically, he graduated a year early at seventeen, in 1892, and studied political science at the University of Budapest under Ágost Pulszky; he was also strongly influenced by Gyula Pikler, though he would later reject the latter's "doctrinaire, anti-historical positivism."[4] At this point he admired figures like József Eötvös and Pál Gyulai, thus aligning himself with "the principled European strand of Hungarian liberalism that stood against clericalism and the blustering nationalism of those who sought independence from Austria."[5] He was awarded his diploma as Doctor of Political Science on July 2, 1896.

Jászi then entered the Department of Economics in the Ministry of Agriculture as a drafting clerk, remaining there for a decade; he received little pay at first but had a great deal of free time. He studied Hungary's agricultural policies and realized the "rigid and ruthless class character" of the country's administration. As a civil servant, he was not permitted to write on political subjects, so his articles began appearing under the name "Oszkár Elemér." In the summer of 1899, he and a number of his friends began planning a new periodical which would present social issues in a more down-to-earth way than in scholarly journals; it was named Huszadik Század (Twentieth Century), and began publication in January 1900. Jászi was the intellectual driving force; "it was he who, with the occasional tough, combative article, declared war on scientific narrow-mindedness and political 'reactionism.'"[6] A year later, in January 1901, Jászi and his friends founded the Sociological Society, which immediately became a venue for sharp debates.

Political career edit

At the beginning of 1904 his book Art and Morality appeared, and Jászi hoped to begin qualifying as a Privatdozent with the aim of embarking on a university career. But soon politics took over, and he focused on trying to establish a socialist party that would at the same time appeal to Hungarian nationalism. He left for Paris in January 1905 and became acquainted with French academic and political life; he later wrote that the six months he spent there "shook me to the very core of my being and became the big thrill of my life."[7] While there, he wrote an article called "The Sociological Method—Two Opinions" in which he supported the approach of Émile Durkheim. He wrote another article attacking Marx as "the great fetish of socialism," which alienated some of his more radical friends. He came to believe that the Hungarians were "just tardy, pale echoes of the great Western efforts, with no intellectual trend emerging from Hungarian soil to have a substantial impact on world civilization."[8]

He returned to Hungary in the midst of a constitutional crisis. The Liberal Party of István Tisza, which had been the governing party for three decades, had lost the February elections, and the emperor-king Franz Josef refused to invite the opposition groups to form a government; instead, he appointed Field Marshal Baron Géza Fejérváry as prime minister, and the opposition called for national resistance. In August, Jászi and some of his friends founded a League for Universal Suffrage by Secret Ballot; this marked the beginning of his political career. The following January, he wrote that "the constitution of today no longer corresponds to Hungary that half a century of its economic and cultural labors have created ... the key to the situation is in the hands of Hungarian organized labor"; in June 1906, he resigned from his position at the Ministry.

In 1908 Jászi and his friends "became associated with Freemasonry, with Jaszi the head of a separate lodge; and this connection was the prime reason why in Hungary Freemasonry was linked with progressive change.[9] In 1910 he was appointed Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Kolozsvár, where he continued to refine and propagate his political opinions; in the words of Hugh Seton-Watson, "Jászi hoped that, if only the degenerate political class could be removed from power, land be distributed to the peasants, and the vote be given to all citizens, a new Hungary could arise in which one Magyar culture could coexist with many languages."[10]

On June 6, 1914, Jászi united a number of progressive groups into the Országos Polgári Radikális Párt (National Civic Radical Party), which called for a universal suffrage, radical land reform, an autonomous customs area, and state control of education. Within six weeks World War I broke out; "the new party supported the pacifist movement and called for the founding of a federation of states for the whole of Europe, a kind of forerunner of the League of Nations."[11]

Aster Revolution edit

In the October Revolution of 1918, Jászi entered the Károlyi government as Minister of Nationalities; he "planned to induce the leaders of the various peoples, mainly the Romanians, Slovaks, and Ruthenians, to keep their people within the borders of Hungary by offering them maximum autonomy," but the attempt failed.[12]

Jászi resigned from the Károlyi government in December 1918, believing that no serious progress in the nationalities question would be possible owing to the arbitrary partitioning of Hungary by the victorious Entente powers. "I hoped that release from the burdens of office and from the obligations of cabinet solidarity would enable me to put forward my views more energetically," Jászi later recalled in his memoirs.[13] Jászi hoped for the establishment of a Danube Confederation of nationalities patterned on the Swiss model. When Jászi became the new Minister for National Minorities of Hungary, immediately offered democratic referendums about the disputed borders for minorities; however, the political leaders of those minorities refused the very idea of democratic referendums regarding disputed territories at the Paris peace conference.[14] After the Hungarian unilateral self-disarmament, Czech, Serbian, and Romanian political leaders chose to attack Hungary instead of holding democratic plebiscites concerning the disputed areas.[15]

On March 21, 1919, the liberal-democratic Károlyi government was replaced by a new Soviet-influenced regime headed by Béla Kun and the second phase of the Hungarian revolution began.

Jászi later recalled that he advised the members of the Radical Party, dissolved in the aftermath of the Communist revolution, that "they should accept neither political or moral responsibility for the Communist regime, but should on no account attempt to copy the sabotage of the Russian intelligentsia; leaving politics aside, they should bend their minds to assisting the new system in the administrative and economic fields."[16]

Jászi emigrated from Hungary on May 1, 1919. In his published memoir of the 1918-19 revolution, Jászi cited his inability to tolerate "the complete denial of freedom of thought and conscience" which characterized the Red regime as well as his expectation of the regime's imminent collapse and its succession by a violent counter-revolutionary regime as reasons for his departure.[17]

Later life edit

He went to the United States in 1925 and joined the faculty of Oberlin College, where he settled down to a career as a history professor and wrote a series of books, the best known of which is The Dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy, first published by the University of Chicago Press in 1929.

Jászi died in Oberlin, Ohio on February 13, 1957.

Bibliography edit

Books edit

- Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Hungary. London: P.S. King & Son, 1924.

- The Dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1929.

- Proposed Roads to Peace. New York: The Abingdon Press, 1932.

- Against the Tyrant: The Tradition and Theory of Tyrannicide. With John D. Lewis. Chicago: Free Press, 1957.

- Homage to Danubia. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995.

Articles edit

- "Dismembered Hungary and Peace in Central Europe," Foreign Affairs, vol. 2, no. 2 (Dec. 15, 1923), pp. 270–281.

- "How a New Lourdes Arises," The Slavonic Review, vol. 4, no. 11 (December 1925), pp. 334–346.

- "Kossuth and the Treaty of Trianon," Foreign Affairs, vol. 12, no. 1 (October 1933), pp. 86–97.

- "Neglected Aspects of the Danubian Drama," The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 14, no. 40 (July 1935), pp. 53–67.

- "Feudal Agrarianism in Hungary," Foreign Affairs, vol. 16, no. 4 (July 1938), pp. 714–718.

- "Political Refugees," The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 203 (May 1939), pp. 83–93.

- "The Stream of Political Murder," American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 3, no. 3 (April 1944), pp. 335–355.

- "The Choices in Hungary," Foreign Affairs, vol. 24, no. 3 (April 1946), pp. 453–465.

- "Danubia: Old and New," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 93, no. 1 (Apr. 18, 1949), pp. 1–31.

References edit

- ^ György Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet: Oscar Jászi 1875-1957. Central European University Press, 2006; pg. 1.

- ^ Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet, pp. 3-4.

- ^ Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet, pg. 5.

- ^ Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet, pg. 6.

- ^ Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet, pg. 9.

- ^ Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet, pg. 19.

- ^ Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet, pg. 35.

- ^ Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet, pg. 41.

- ^ Chris Wrigley, Challenges of Labour: Central and Western Europe, 1917-1920 London: Routledge, 1993; pg. 76.

- ^ Hugh Seton-Watson, Nations and States: An Enquiry into the Origins of Nations and the Politics of Nationalism. London: Taylor & Francis, 1977; pg. 167.

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch, A History of Modern Hungary, 1867-1994. White Plains, NY: Longman, 1996; pg. 73.

- ^ Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, and Tibor Frank, A History of Hungary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994; pg. 298.

- ^ Oscar Jászi, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Hungary. London: P.S. King & Son, 1924; pg. 86.

- ^ Adrian Severin; Sabin Gherman; Ildiko Lipcsey (2006). Romania and Transylvania in the 20th Century. Corvinus Publications. p. 24. ISBN 9781882785155.

- ^ Bardo Fassbender; Anne Peters; Simone Peter; Daniel Högger (2012). The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780199599752.

- ^ Jászi, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Hungary, pg. 111.

- ^ Jászi, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Hungary, pg. 110.

Sources edit

- Nina Bakisian, "Oscar Jászi in Exile: Danubian Europe Reconsidered," Hungarian Studies, vol. 9, no. 1/2 (1994), pp. 151–159.

- György Litván, A Twentieth-Century Prophet: Oscar Jászi 1875-1957 (Central European University Press, 2006)