Nawab Kapur Singh (1697 – 9 October 1753) was a major Sikh leader who led the community during the early-to-mid 18th century. He was the organizer of the Sikh Confederacy and its military force, the Dal Khalsa. He is held in high regards by Sikhs.[1]

Kapur Singh | |

|---|---|

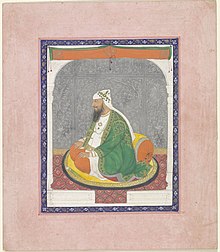

Posthumous portrait of Nawab Kapur Singh from 1850's | |

| Jathedar of the Akal Takht | |

| In office 1737 – 9 October 1753 | |

| Preceded by | Darbara Singh |

| Succeeded by | Jassa Singh Ahluwalia |

| 3rd Jathedar of Buddha Dal | |

| In office 29 March 1748 – 9 October 1753 | |

| Preceded by | Darbara Singh |

| Succeeded by | Jassa Singh Ahluwalia |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kapur Singh 1697 Kaloke, Lahore Subah, Mughal Empire (present-day Sheikhupura district, Punjab, Pakistan) |

| Died | 9 October 1753 (aged 55–56) Amritsar, Punjab, Durrani Empire (present-day Punjab, India) |

| Parent |

|

| Military service | |

| Founder | |

Early life

editNawab Kapur Singh was born into the Virk clan of Jat in 1697.[2] His native village was Kaloke, now in the Sheikhupura district of Punjab, Pakistan. When he seized the village of Faizullapur, near Amritsar, he renamed it Singhpura and made it his headquarters. He is thus, also known as Kapur Singh Faizullapuria, and the small principality he founded, as Faizullapuria or Singhpuria.[3][4]

Initiation into the Khalsa fold

editIn 1721, Kapur Singh underwent amrit-initiation at a large gathering held at Amritsar on Vaisakhi Day, from Panj Piarey led by Bhai Mani Singh.[5]

The title of Nawab

editIn 1733, the Mughal government decided, at the insistence of Zakarya Khan, to revoke all repressive measures issued against the Sikhs and made an offer of a grant to them. The title of Nawab was conferred upon their leader, with a jagir consisting of the three parganas of Dipalpur, Kanganval and Jhabal.[6]

During a Sarbat Khalsa, Baba Darbara Singh was offered to be Nawab. Since he rejected this, Kapur Singh was offered the Nawabship and he accepted.[7]

Formation of the Dal Khalsa

editWith the arrival of peace with the Mughals, Sikhs returned to their homes and Kapur Singh undertook the task of consolidating the disintegrated fabric of the Sikh Jathas. These were merged into a single central fighting force (The Dal) divided into two sections: the Budha Dal was the army of the veterans, and the Taruna Dal became the army of the young, led by Hari Singh Dhillon. The former was entrusted with looking after the holy places, preaching the word of the Gurus and inducting converts into the Khalsa Panth by holding baptismal ceremonies. The Taruna Dal was the more active division and its function was to fight in times of emergencies.[citation needed]

Kapur Singh's personality was the common link between these two wings. He was universally respected for his high character. His word was obeyed willingly and to receive baptism at his hands was counted an act of rare merit.[8][full citation needed]

Rise of the Misls

editUnder Hari Singh's leadership, the Taruna Dal rapidly grew in strength and soon numbered more than 12,000. To ensure efficient control, Nawab Kapur Singh split it into five parts, each with a separate centre. Each part had its own banner and drum, and formed the nucleus of a separate political state. The territories conquered by these groups were entered in their respective papers at the Akal Takht by Jassa Singh Ahluwalia. From these documents or misls, the principalities carved out by them came to known as Misls. Seven more groups were formed subsequently and, towards the close of century, there were altogether twelve Sikh Misls ruling the Punjab.[9]

Death

editNawab Kapur Singh requested the community to relieve him of his office, due to his old age, and at his suggestion, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was chosen as the supreme commander of the Dal Khalsa. Kapur Singh died on 9 October 1753 at Amritsar and was succeeded by his nephew (Dhan Singh's son), Khushal Singh.[10]

Legacy

editThe village of Kapurgarh in Nabha is named after Nawab Kapur Singh.[11]

Battles

edit- Battle of Thikriwala (1731)

- Battle of Sunam (1735)

- Battle of Sirhind (1735)

- Battle of Basarke (1736)

- Battle of Amritsar (1738)

- Samad Khan's expedition against the Sikhs (1738)

- Skirmish of Chenab (1739)

- Battle of Kahnuwan (1746)

- Siege of Amritsar (1748)

- Battle of Kahnuwan (1752)[12]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ W. H. McLeod, Louis E. Fenech (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman and Littlefield lpublishers. p. 172. ISBN 9781442236011.

- ^ Dhavan, Purnima (2011). When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699-1799 (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0199756551. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Singh, Harbans (1965). The Heritage of the Sikh. Asia Publishing House. p. 52.

- ^ Singha, Dr H. S. (2005). Sikh Studies. Hemkunt Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-81-7010-258-8.

- ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (1999). Sikhs in the Eighteenth Century. the university of Michigan. p. 86. ISBN 9788172052171.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (1980). Struggle of the Sikhs for Sovereignty. Guru Das Kapur. p. 335.

- ^ Gupta, Hari Ram (1998). History of the Sikhs Volume 4. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Private, Limited. p. 72. ISBN 9788121505406.

- ^ The Sikh Review - Volume 27. the university of Michigan. 1979. p. 56.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (1999). Sikhs in the Eighteenth Century. Singh Bros. p. 413. ISBN 9788172052171.

- ^ Punjab District Gazetteers: Amritsar. Supplement. the University of Michigan: Punjab India. 1976. p. 606.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (1963). A History of the Sikhs: 1469-1839. Princeton University Press. p. 123.

- ^ Singh, Sawan (2005). Noble and Brave Sikh Women. B.Chattar Singh Jiwan Singh. p. 11. ISBN 9788176017015.