This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (French: [ʒozɛf miʃɛl mɔ̃ɡɔlfje]; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810)[1] and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier ([ʒak etjɛn mɔ̃ɡɔlfje]; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799)[1] – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune Annonay in Ardèche, France. They invented the Montgolfière-style hot air balloon, globe aérostatique, which launched the first confirmed piloted ascent by humans in 1783, carrying Jacques-Étienne.

The Montgolfier brothers | |

|---|---|

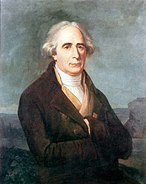

Joseph-Michel (left) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, late 18th century | |

| Born | Joseph-Michel: 26 August 1740, Annonay, Ardèche, France Jacques-Étienne: 6 January 1745, Annonay, Ardèche, France |

| Died | Joseph-Michel: 26 June 1810 (aged 69), Balaruc-les-Bains, France Jacques-Étienne: 2 August 1799 (aged 54), Serrières, France |

| Occupation(s) | Inventors, balloonists, paper manufacturers |

| Known for | Making the first confirmed human flight, in a Montgolfière-style hot air balloon |

Joseph-Michel also invented the self-acting hydraulic ram (1796) and Jacques-Étienne founded the first paper-making vocational school. Together, the brothers invented a process to manufacture transparent paper.

Early years

editJoseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier were born into a family of paper manufacturers. Their parents were Pierre Montgolfier (1700–1793) and Anne Duret (1701–1760), who had 16 children.[1] Pierre Montgolfier established his eldest son, Raymond (1730–1772), as his successor.[citation needed]

Joseph-Michel was the 12th child. Described[by whom?] as a maverick and dreamer, he was impractical in terms of business and personal affairs. Étienne was the 15th child, had a much more even and businesslike temperament and was sent to Paris to train as an architect. After the sudden and unexpected death of Raymond in 1772, he was recalled to Annonay to run the family business. In the subsequent 10 years, Étienne applied his talent for technical innovation to the family business of paper making, which then as now was a high-tech industry. He succeeded in incorporating the latest Dutch innovations of the day into the family mills.[citation needed]

Hot air balloon experiments, 1782–84

editHot air balloon experiments, 1782

editOf the two brothers, it was Joseph who was first interested in aeronautics; as early as 1775 he built parachutes, and once jumped from the family house. He first contemplated building machines when he observed laundry drying over a fire incidentally form pockets that billowed upwards.[2] Joseph made his first definitive experiments in November 1782 while living in Avignon. He reported some years later that he was watching a fire one evening while contemplating one of the great military issues of the day—an assault on the fortress of Gibraltar, which had proved impregnable from both sea and land.[3] Joseph mused on the possibility of an air assault using troops lifted by the same force that was lifting the embers from the fire. He believed that the smoke itself was the buoyant part and contained within it a special gas, which he called "Montgolfier Gas", with a special property he called levity, which is why he preferred smoldering fuel.

Joseph then built a box-like chamber 0.9 by 0.9 by 1.2 metres (3 ft × 3 ft × 4 ft) out of very thin wood, and covered the sides and top with lightweight taffeta cloth. He crumpled and lit some paper under the bottom of the box. The contraption quickly lifted off its stand and collided with the ceiling.

Joseph recruited his brother to balloon building by writing, "Get in a supply of taffeta and of cordage, quickly, and you will see one of the most astonishing sights in the world." The two brothers built a similar device, three times larger having a volume 27 times greater. On 14 December 1782 they conducted their very first test flight, using ignited wool and hay as fuel. The lifting force was so great that they lost control of their craft. The device floated nearly two kilometers (1.2 mi) but was destroyed after landing by the "indiscretion" of a bypasser.[4]

Public demonstrations, summer 1783

editTo make a public demonstration and to claim its invention the brothers constructed a globe-shaped balloon of sackcloth tightened with three thin layers of paper inside. The envelope could contain nearly 790 m3 (28,000 cu ft) of air and weighed 225 kg (496 lb). It was constructed of four pieces (the dome and three lateral bands) and held together by 1,800 buttons. A reinforcing fish net of cord covered the outside of the envelope.

On 4 June 1783, they flew the balloon at Annonay in front of a group of dignitaries from the états particuliers. The flight covered 2 km (1.2 mi), lasted 10 minutes, and had an estimated altitude of 1,600–2,000 m (5,200–6,600 ft). Word of their success quickly reached Paris. Étienne went to the capital to make further demonstrations and to solidify the brothers' claim to the invention of flight. Joseph, given his unkempt appearance and shyness, remained with the family. Étienne was the epitome of sober virtues ... modest in clothes and manner...[5]

In collaboration with the wallpaper manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, Étienne constructed a 37,500-cubic-foot (1,060 m3) envelope of taffeta coated with a varnish of alum for fireproofing. The balloon was sky blue and decorated with golden flourishes, signs of the zodiac, and suns. The design showed the intervention of Réveillon. The next test was on 11 September from the grounds of la Folie Titon, close to Réveillon's house. There was some concern about the effects of flight into the upper atmosphere on living creatures. The king proposed to launch two convicted criminals, but it is most likely that the inventors decided to send a sheep, a duck, and a rooster aloft first.

On 19 September 1783, the Aérostat Réveillon was flown with the first living beings in a basket attached to the balloon: a sheep called Montauciel ("Climb-to-the-sky"), a duck and a rooster. The sheep was believed to have a reasonable approximation of human physiology. The duck was expected to be unharmed by being lifted and was included as a control for effects created by the aircraft rather than the altitude. The rooster was included as a further control as it was a bird that did not fly at high altitudes. The demonstration was performed at the royal palace in Versailles, before King Louis XVI of France and Queen Marie Antoinette and a crowd.[6] The flight lasted approximately eight minutes, covered two miles (3.2 km), and obtained an altitude of about 1,500 feet (460 m). The craft landed safely after flying.

Piloted flight, autumn 1783

editSince the animals survived, the king allowed flights with humans. Again in collaboration with Réveillon, Étienne built a 60,000-cubic-foot (1,700 m3) balloon for the purpose of making flights with humans. It was about 23 m (75 ft) tall and about 15 m (49 ft) in diameter. Réveillon supplied rich decorative touches of gold figures on a deep blue background, including fleur-de-lis, signs of the zodiac, and suns with Louis XVI's face in the center interlaced with the royal monogram in the central section. Red and blue drapery and golden eagles were at the base of the balloon. Étienne Montgolfier was the first human to lift off the Earth in a balloon, making a tethered test flight from the yard of the Réveillon workshop in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, most likely on 15 October 1783. A little while later on that same day, physicist Pilâtre de Rozier became the second to ascend into the air, to an altitude of 80 feet (24 m), which was the length of the tether.[7][8]

On 21 November 1783, the first free flight by humans was made by Pilâtre de Rozier, together with an army officer, the marquis d'Arlandes.[9] The flight began from the grounds of the Château de la Muette close to the Bois de Boulogne park in the western outskirts of Paris. They flew about 3,000 feet (910 m) above Paris for a distance of nine kilometers. After 25 minutes, the balloon landed between the windmills, outside the city ramparts, on the Butte-aux-Cailles. Enough fuel remained on board at the end of the flight to have allowed the balloon to fly four to five times as far. However, burning embers from the fire were scorching the balloon fabric and had to be daubed out with sponges. As it appeared it could destroy the balloon, Pilâtre took off his coat to stop the fire.[citation needed]

The early flights made a sensation. During those first few years, numerous items, such as fans, furniture, handkerchiefs, pencil boxes, umbrella tops, etc., could be found with ballooning images engraved on them. Some items would be celebrating specific ballooning events, while others would be celebrating ballooning itself.[10]

In December 1783, father Pierre Montgolfier was elevated to the nobility and the hereditary appellation of de Montgolfier by King Louis XVI of France.

Other balloons, competing claims

editSome claim that the hot air balloon was invented about 74 years earlier by the Brazilian/Portuguese priest Bartolomeu de Gusmão.[11] A description of his invention was published in 1709(?) in Vienna, and another one was found in the Vatican in about 1917.[12] However, this claim is not generally recognized by aviation historians outside the Portuguese-speaking community, in particular the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

On 1 December 1783, a few months after the Montgolfiers' first flight, Jacques Alexandre César Charles rose to an altitude of about 3 km (1.9 mi) near Paris in a hydrogen-filled balloon he had developed.

In early 1784, the Flesselles balloon, named after the unfortunate Jacques de Flesselles, later to be an early casualty at the Bastille, gave a rough landing to its passengers.[13]

In June 1784, the Gustave (a hot air balloon christened La Gustave in honour of King Gustav III of Sweden's visit to Lyon) saw the first female aeronaut, Élisabeth Thible.

Other Montgolfier inventions

editBoth brothers invented a process to manufacture transparent paper similar to vellum, imitating the technique of the English, followed by the papermakers Johannot and Réveillon.[14] In 1796, Joseph Michel Montgolfier invented the first self-acting hydraulic ram, a water pump to raise water for his paper mill at Voiron.[15] In 1772, the British clockmaker John Whitehurst had invented its precursor, the "pulsation engine". In 1797, Montgolfier's friend Matthew Boulton took out a British patent on his behalf.

In 1816, Joseph Michel's sons obtained a British patent for an improved version of the pump.[16]

Death, the Montgolfier company

editBoth brothers were freemasons in Les Neuf Soeurs lodge in Paris.[17]

In 1799, Etienne de Montgolfier died on the way from Lyon to Annonay.[18] His son-in-law, Barthélémy Barou de la Lombardière de Canson (1774–1859), succeeded him as the head of the company, thanks to his marriage with Alexandrine de Montgolfier. The company became Montgolfier et Canson in 1801, then Canson-Montgolfier in 1807. In 1810, Joseph-Michel died in Balaruc-les-Bains.[18]

The Montgolfier Company in Annonay still exists under the name Canson. It produces fine art papers, school drawing papers and digital fine art and photography papers sold in 150 countries.[19]

In 1983, the Montgolfier brothers were inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[20]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier: French Aviators". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ Gillispie, C. C. The Montgolfier brothers and the invention of aviation 1783–1784, p. 15.

- ^ Gillispie, p. 16.

- ^ Gillispie, p. 21.

- ^ Schama, S. (1989). Citizens. A Chronicle of the French Revolution, p. 125.

- ^ Gillispie, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Crouch, Tom Davis (2009). Lighter Than Air. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 28, 178.

- ^ Gillispie, Charles (1983). The Montgolfier Brothers, and the Invention of Aviation. Princeton University Press. pp. 45, 46, 178, 179, 183–185.

- ^ "U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission: Early Balloon Flight in Europe". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ Brant, Clare (2017). Balloon Madness: Flights of Imagination in Britain, 1783–1786. The Boydell Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-78327-253-2.

- ^ Reis, Fernando. Bartolomeu de Gusmão.Ciência em Portugal. Archived 19 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine Centro Virtual Camões, in Portuguese

- ^ Gusmao, Bartolomeu de. Reproduction fac-similé d'un dessin à la plume de sa description et de la pétition addressée au Jean V. (de Portugal) en langue latine et en écriture contemporaine (1709) retrouvés récemment dans les archives du Vatican du célèbre aéronef de Bartholomeu Lourenco de Gusmão "l'homme volant" portugais, né au Brésil (1685–1724) précurseur des navigateurs aériens et premier inventeur des aérostats. 1917 (Lausanne: Impr. Réunies S. A.) (in French and Latin)

- ^ Gillispie, Charles (1983). The Montgolfier Brothers and the Invention of Aviation 1783–1784 : With a Word on the Importance of Ballooning for the Science of Heat and the Art of Building Railroads. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0691083216.

- ^ Our History 1777 Canson, n.d., 2 July 2017

- ^ de Montgolfier, J.M. (1803). "Note sur le bélier hydraulique, et sur la manière d'en calculer les effets" [Note on the hydraulic ram, and on the method of calculating its effects] (PDF). Journal des Mines, 13 (73) (in French). pp. 42–51.

- ^ See, for example: "New Patents: Pierre François Montgolfier" The Annals of Philosophy, 7 (41) : 405 (May 1816).

- ^ Dictionnaire de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Daniel Ligou, Presses Universitaires de France, 2006)

- ^ a b "Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Our Values Canson, n.d., 2 July 2017

- ^ Sprekelmeyer, Linda, editor. These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame. Donning Co. Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57864-397-4.