Marie Léonide Charvin was a French theater actress, better known by her stage name Agar. She was born in Sedan on September 18, 1832, and died on August 15, 1891, to Sidi M'Hamed in Algeria. She starred in some of the most famous French Plays of the 19the Century such as Cinna by Pierre Corneille, Athalie, Phèdre, Andromaque and Britannicus by Jean Racine and Le Passant by François Coppée. She also worked with some of the most famous actresses of their time such as Rachel Félix and Sarah Bernhardt. Upon her death Pauline Savari said “Above all in love with the great heroines, in turn Camille, Phèdre, Hermione and Emilie, she did not lavish her admirable talent in numerous and fleeting creations; but if it had only the two roles of the passer-by, that touching inspiration of François Coppée, and of the enemy mothers, the master and powerful work of Catulle Mendès! That would already be glory!" Marie Léonide Charvin is known as one of the most famous actresses of the late 19th century.[1]

Marie Leonide Charvin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 18, 1832 |

| Died | August 15, 1891 (aged 59) Mustapha Algeria |

| Citizenship | France |

| Occupation | French actress |

Biography edit

Early life edit

Marie Léonide Charvin was the daughter of Pierre Charvin, then aged 32, sergeant at 8th Regiment of Light Cavalry stationed at Sedan, and Mary Fréchuret, then aged 17 years.[2]

Her parents are from Isère, her father from Faramans and her mother from Vienne, it seems that, while her parents continue to lead the garrison life linked to her father's profession, Marie Léonide lived a childhood and a quiet youth with his paternal grandparents in Faramans.[3]

She married a man named Nique, to escape the influence of her father's new wife, who had remarried since her widowhood in 1848. Due to abuse from Nique, after five years she fled to Paris in 1853.[4]

Apprenticeship in Europe edit

She began her life in Paris by giving lessons in piano and then, as she had "The Voice", begins to sing, from 1857, in café-concerts, the "Bellowing" under the pseudonym Marie Lallier, songs "Specially composed for her talent, which she interpreted "with a certain tragic vigor".[5]

In 1859, she went for the first time on the stages of a real theater, the Beaumarchais theater, as a singer to perform a cantata in honor of Solferino victory. Presented to the drama teacher Ricourt, the latter advises her to rejuvenate and makes her change her name and choose that of Agar, on the grounds "that after Rachel's great successes, all the actresses had to take their name in the Bible”.[6]

At the end of 1859, under his direction, she began as an actress at the small theater of the Tour d'Auvergne, in Don César de Bazan by Dumanoir and Dennery, where she played the role of Maritana . Having become “the star” of this theater, she then played Phèdre for the first time on March 6, 1860. A brochure from 1862 comments: “ Phèdre, my God, yes! she [ Agar] who, six weeks before, had no idea that there was a play of this name Unfortunately the lessons were still being felt in diction”.

Francisque Sarcey, dramatic critic, describes it as follows: “one day I let myself be taken to his class [at Ricourt's] to see the marvel of which he had made himself the precursor. It was Agar. She was superb, with that beautiful marble face, that thick black hair, heavily massaged on the neck, her already opulent breasts, her majestic waist and that deep voice to which her veiled tone gave something mysterious. It was somebody!"[7]

Career edit

First success in theater edit

On January 20, 1862, on the stage of the Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe, she takes on the role of Phèdre de Racine. "She had, in front of the young and intelligent audience of this theater, a great beauty success, and her abrupt, rough, little measured talent, but of a personal, strange and communicative inspiration, produced a very lively effect". They will then be roles in Horace by Corneille, Agnès de Méranie by François Ponsard, Medea by Ernest Legouvé at the Lyric School, Lucrèce also by François Ponsard as well as an important role in a drama by Mr. Garand, the Stranglers of India, at the Porte-Saint-Martin theater.[8]

His first appearance on the stage of the Comédie-Française dates from May 12, 1863. She once again interprets the role of Phèdre. This beginning is especially noted for an accident:"By leaving the first act, Agar fell on a grid of the stove and she injured in the face and especially the nose. She was nevertheless able to perform the two following acts; but in the fourth, it took down the curtain without finishing the piece, Agar being found wrong".

His subsequent performances on this prestigious stage, in the works of Racine, Andromaque and the role of Clytemnestra in Iphigénie, have only “success that does not meet expectations”.[9]

Leaving rue de Richelieu, she found herself on the boards of Ambigu in La Sorcière then, in 1864, of Porte-Saint-Martin in Faustine by Louis-Hyacinthe Bouilhet, of Gaîté on boulevard du Temple in the Tour of Nesle by Frédéric Gaillardet and Alexandre Dumas, in the role of Ghébel in Le Fils de la nuit by Alexandre Dumas and Gérard de Nerval, and again of the Odeon in La Conjuration d'Amboise by Bouilhet in 1866 with the role of the Queen mother, in King Lear according to Shakespeare and in Jeanne de Lignières .[10]

Notoriety edit

Marie Léonide maintains a friendly relationship with a young poet, François Coppée, who has just made his first play, a one-act verse comedy with two characters, entitled Le Passant. She obtains from the direction of the Odeon that this piece be included in the repertoire and thus finds herself in the role of Silvia alongside Sarah Bernhardt who plays that of the troubadour Zanetto, January 14, 1869. These performances turn out to be a success for the two tragedians as well as for the author.[11]

This success reopens Agar the doors of the Comédie-French where the June 6 in 1869. She performed "to its greatest advantage" in the role Emilia Cinna of Corneille :"She relaxed treble sides of her talent and she made the best efforts to break with some of its native traditions ”. She is now considered "Unquestionably, the first tragedian of the Théâtre-Français".[12]

Much applauded, she followed the roles on this scene: in July that of Camille in Horace by Corneille then the title role in Phèdre by Racine, in September that of Hermione in Andromache by Racine, and in October the role of Andromache she - even in this latest tragedy.[13]

the July 20, 1870, After the declaration of war from France to Prussia, during a performance of the Lion lover of François Ponsard, the public demands, as he already did the day before, the 18th, to hear between two acts the orchestra playing La Marseillaise. This time, Agar, part of the cast of the play, "advances and declaims with energy manly stanzas whose dining repeated every time the refrain".

From that day on, the public demanded that the tragic actress come and sing the Marseillaise every night regardless of the show on offer, which she did forty-four times in a row until the closure of theater . Théophile Gautier comments: "She does not sing La Marseillaise precisely, but she mixes the melody with the recitation in a very skillful way and the effect it obtains is very great. She makes the momentum predominate. heroic and the certainty of triumph ”[14]

The communard edit

During the Paris Commune started in March 1871, it occurs in favor of this cause on April 30 for a morning at the Vaudeville theater, May 14 at the Tuileries, then the May 21st for a concert for the benefit of the wounded and the widows and orphans of the national guards killed, while the Versailles troops entered Paris.

May 6, 1871, the government of the Commune organized a concert at the Tuileries, for the benefit of the widows and orphans of the Federates, and asked the Comédie-Française for the assistance of an artist to recite La Marseillaise. Édouard Thierry, then administrator and guardian of the Comédie-Française, advised Marie Leonide Agar to accept... This evening was made a crime for the poor artist who, in all defense, was content to respond invariably:"I am everywhere I go. then to help the unfortunate. "It was enough for the situation of Marie LeonideAgar became impossible for the Comédie-Française, which it left in 1872 to undertake long and painful tours in the provinces .

Eclipses, resurgences and outcome edit

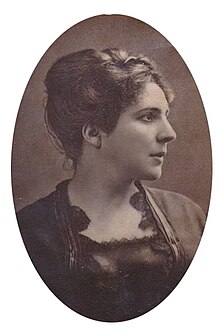

Portrait by Félix Nadar, Supported by Georges Marye and Paul Bourget, Marie Léonide only makes rare appearances on the Parisian scene. We see her again in 1875 at the Porte-Saint-Martin theater and at the Renaissance theater, then in 1877 at the Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique.

On April 8, 1878, after six years of ostracism, the Comédie-French it reopens in entrusting the role of Marie Leonide Bernard in the Fourchambault of Emile Augier. She achieved great success there, then played the title role of Athalie de Racine, that of Agrippina in Britannicus by the same author, took over roles in Le Village by Octave Feuillet and Les Ouvriers by Nicolas Brazier and Théophile Marion Dumersan.

However, not having been appointed member of the Comédie-Française at the end of the year, Marie Léonide was annoyed and hit the road again.

Widowed in 1879 by her first husband (Nique), in 1880 she married Georges Marye, curator of African antiquities in Algiers.

Paris found her in 1882 and 1883 on the Ambigu stage in the role of Princess Boleska in Les Mères ennemies by Catulle Mendès, then in that of Marie in La Glu by Jean Richepin.

Once again, the shadow of the Comédie-Française hangs over its destiny; she finds her place as a boarder by September 1885 for the role of Queen Mother Gertrude in Hamlet after William Shakespeare, while continuing to hope for membership.[15]

It is sick, tired, discouraged that she will live the last years of her existence while harboring a certain bitterness, even resentment, towards the house of Molière by remembering "Her seven lost years at the Theater. -French ”.

She is the intimate friend of Pauline Savari, her pupil, who organizes for her, which paralysis has struck, and whose resources are rather precarious, a "Benefit Performance" in May 1889.[16]

“Above all in love with the great heroines, in turn Camille, Phèdre, Hermione and Emilie, she did not lavish her admirable talent in numerous and fleeting creations; but if it had only the two roles of the passer-by, that touching inspiration of François Coppée, and of the enemy mothers, the master and powerful work of Catulle Mendès, eh! that would already be glory!"- Pauline Savari

In 1890, aged 58, while reciting Victor Hugo's poem Le Cimetière d'Eylau, it was on stage that she was struck by paralysis; an entire side of his body is inert.

August 15, 1891, Agar died in her home in Algiers. She was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery in the 9 th Division. On her tomb is placed a reproduction of the beautiful bust of the tragedian by the statuary Henry Cros.[17]

François Coppée, during the inauguration of the bust, declaimed these verses on his grave:

- Translated:

- Others will recall that your fate, poor woman,

- Was rigorous, despite so many bright evenings,

- That one disputed its throne with the queen of the drama

- And an unjust forgetfulness exiled him too long.

In 1910, a medallion in honor of the actress was inaugurated at the Odeon, held its first stage success.[18]

Civil status ambiguities edit

Starting with her own statements, certain ambiguities persist about her first names, date and place of birth.

The first name of Marie is sometimes replaced by that of Florence (commemorative plaque affixed in 1917 by the municipality of Algiers on the house where she died).

The same commemorative plaque gave birth to it in 1836, rejuvenating it by four years, in the town of Saint-Claude (Jura). The city of Vienne (Isère) is also cited as the place of birth well as the city of Valence (Drôme). Agar herself claimed to have been born in Bayonne ( Pyrénées-Atlantiques) in September 1837 when she registered with the Association of Artists.

The date of August 14 is sometimes cited for her death.[19]

Theater edit

Comédie-Française edit

- 1869 : Cinna by Pierre Corneille : Émilie

- 1878 : The Fourchambault d ' Émile Augier : Marie Leonide Bernard

- 1878 : Athalie by Jean Racine : Athalie

- 1878 : Britannicus by Jean Racine : Agrippina

Outside the Comédie-Française edit

- 1862 : Phèdre by Jean Racine, Odéon theater : Phèdre

- 1869 : Le Passant by François Coppée, Odéon theater: Silvia

- 1873 : Andromaque by Jean Racine, theater in Vevey

Footnotes edit

- ^ "Vienne. Jeudi l'histoire : la triste fin d'Agar, la tragédienne viennoise". www.ledauphine.com (in French). Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ Mansfield, Alyson. "The Departmental Archives of Ardennes - OnGenealogy". Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ "ANOM, Etat Civil, Résultats". anom.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ "Gallica". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ Jowers, Sidney Jackson (2013-10-15). Theatrical Costume, Masks, Make-Up and Wigs: A Bibliography and Iconography. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-74641-3.

- ^ Racine depuis 1885: bibliographie raisonnée des livres--articles--comptes-rendus critiques relatifs à la vie et l'oeuvre de Jean Racine, 1885-1939 (in French). Johns Hopkins Press. 1940.

- ^ Frémont, Léon (1897). Revue de Champagne et de Brie: Histoire - biographie - archéologie - documents inédits - bibliographie - beaux-arts (in French). H. Menu.

- ^ Revue de Champagne et de Brie (in French). 1897.

- ^ Revue d'art dramatique (in French). Librairie Molière. 1895.

- ^ Revue d'Ardenne et d'Argonne (in French). 1910.

- ^ Besson, Nicolas François Louis (1897). Annales Franc-Comtoises (in French).

- ^ Axelrad, Jacob (1944). Anatole France: A Life Without Illusions, 1844-1924 ... Harper & Brothers.

- ^ Polybiblion: revue bibliographique universelle (in French). Aux bureaux de la revue. 1903.

- ^ Bernhardt, Sarah (1999-01-01). My Double Life: The Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4053-7.

- ^ Bernhardt, Sarah (1999-01-01). My Double Life: The Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4053-7.

- ^ Kalmar, Pierre; Vel, Donatien (2016). Par la barbe de Louis-Benjamin ! Deux étudiants de Grenoble, originaires de Valence, écrivent à leurs parents (in French). Lulu.com. ISBN 978-2-919341-48-1.

- ^ University, Johns Hopkins (1931). Studies in Romance Literatures and Languages: Extra Volumes (in French). Johns Hopkins Press.

- ^ Pagnotta, Linda (2009). Volti e figure: il ritratto nella storia della fotografia (in Italian). Apax libri. ISBN 978-88-88149-54-7.

- ^ Goncourt, Edmond de; Goncourt, Jules de (1956). Journal: Mémoires de la Vie Littéraire (in French). Fasquelle.

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (February 2022) |