The King African mole-rat,[3] King mole-rat,[4] or Alpine mole-rat,[5] (Tachyoryctes rex) is a burrowing rodent in the genus Tachyoryctes of family Spalacidae.[6] It only occurs high on Mount Kenya, where it is common. Originally described as a separate species related to Aberdare Mountains African mole-rat, (T. audax) in 1910, some classify it as the same species as the East African mole-rat, (T. splendens).

| King African mole-rat | |

|---|---|

| |

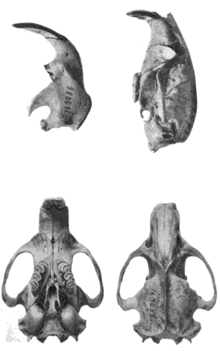

| Holotype skull and mandible of Tachyoryctes rex.[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Spalacidae |

| Genus: | Tachyoryctes |

| Species: | T. rex

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tachyoryctes rex | |

It is a very large, brownish species, with head and body length ranging from 222 to 268 mm (8.7 to 10.6 in). The young are dark with irregular white patches on their underparts. The animal builds large burrows and perhaps associated mounds and eats plant roots.

Taxonomy

editIn 1909, John Alden Loring collected the holotype while on the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition led by Theodore Roosevelt.[7] The next year, Edmund Heller described the species as Tachyoryctes rex; he thought it most closely related to another Kenyan species, T. audax.[2] In 1919, Ned Hollister provided additional information using more material, and affirmed the relationship between T. rex and T. audax. He noted that the two were similar in coloration, but that T. rex was much larger;[8] according to Heller, T. audax is somewhat darker in color.[2] Since 1974, some taxonomic works have included T. rex and many other Tachyoryctes species in T. splendens, though without evaluation of the distinctive characters of the previously recognized species.[9] The 2009 IUCN Red List follows this arrangement,[10] but the 2005 third edition of Mammal Species of the World describes T. rex as a "distinctive species".[3]

Description

editTachyoryctes rex is a very large species with fluffy fur.[8] It is reddish-brown above and lighter brown below. The tip of the snout and the throat are black, and an area around the mouth is white. The feet are brown, but the toes are white. The tail is dark above and off-white below.[2] Males are larger than females. Young animals are dark-furred, with some irregular white areas on their underparts. In young animals, the crown area of the molars is small, but it grows with wear in adulthood until reaching a maximum, after which it shrinks again. The iris is dark gray-brown.[8] In 14 specimens, head and body length is 222 to 268 mm (8.7 to 10.6 in), tail length is 54 to 80 mm (2.1 to 3.1 in), hindfoot length is 29 to 33 mm (1.1 to 1.3 in), and skull (condylobasal) length is 47 to 57 mm (1.9 to 2.2 in).[12]

In comparison to those of Tachyoryctes audax, the nasal bones are larger and have angles at the sides. T. annectens, which is nearly as large, has smaller teeth and nasals; in T. rex, the basioccipital is broader, and the back part of the mandible (lower jaw) is better developed and has the capsule of the incisor placed further to the front.[2]

Distribution, Ecology, and Behavior

editTachyoryctes rex is found on the northern and eastern slopes of Mount Kenya, Kenya, at elevations of up to 4,500 m (15,000 ft).[13] It is common just above the upper limit of forest in the lower moorland.[2] A female found on October 5 had a large embryo.[8] T. rex builds large mounds with diameters up to 6 m (20 ft).[14] Some have interpreted these mounds as being built by termites instead,[15] but termites do not occur at these elevations in Mount Kenya.[16] From those mounds, burrows may extend up to 50 m (160 ft) and be up to 1 m (3.3 ft) deep. One chamber is used for urination and defecation and to store plant matter; it produces a substantial amount of heat. In other chambers, T. rex builds large nests of grass.[17] The animal eats plant roots. Its presence results in a change in vegetation on the mounds, which have fewer grasses and more woody plants,[18] perhaps because the animal eats plant roots or because the soil is altered.[19]

References

edit- ^ Hollister, 1919, plate 15

- ^ a b c d e f Heller, 1910, p. 4

- ^ a b Musser and Carleton, 2005, p. 924

- ^ Duff and Lawson, 2004

- ^ Loring in Roosevelt, 1910, p. 547

- ^ Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Anonymous, 1908; Heller, 1910, pp. 1, 4

- ^ a b c d Hollister, 1919, p. 42

- ^ Musser and Carleton, 2005, pp. 922–923

- ^ Schlitter et al., 2008

- ^ Hausman, 1920, plate III, fig. 103

- ^ Hollister, 1919, p. 45

- ^ Young & Evans (1993). "Alpine Vertebrates of Mount Kenya". Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society and National Museum. 82: 55–92.

- ^ Young & Evans (1993). "Alpine Vertebrates of Mount Kenya". Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society and National Museum. 82: 55–92.

- ^ Darlington, 1985, p. 116

- ^ Young & Evans (1993). "Alpine Vertebrates of Mount Kenya". Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society and National Museum. 82: 55–92.

- ^ Osborne, 2000, p. 293; Hollister, 1919, p. 42

- ^ Young & Evans (1993). "Alpine Vertebrates of Mount Kenya". Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society and National Museum. 82: 55–92.

- ^ Rundel et al., 1994, p. 333

- Anonymous. 1908. President Roosevelt's African trip (subscription required). Science 28(729):876–877.

- Darlington, J.P.E.C. 1985. Lenticular soil mounds in the Kenya highlands (subscription required). Oecologia 66(1):116–121.

- Duff, A. and Lawson, A. 2004. Mammals of the World: A Checklist. Yale University Press, 312 pp.

- Hausman, L.A. 1920. Structural characteristics of the hair of mammals. The American Naturalist 54:496–523.

- Heller, E. 1910. Descriptions of seven new species of East African mammals. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 56(9):1–5.

- Hollister, N. 1919. East African mammals in the United States National Museum. Part II. Rodentia, Lagomorpha, and Tubulidentata. United States National Museum Bulletin 99(2):1–184.

- Musser, G.G. and Carleton, M.D. 2005. Superfamily Muroidea. In: Wilson, D.E. and Reeder, D.M., Eds., Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2142.

- Osborne, P.L. 2000. Tropical ecosystems and ecological concepts. Cambridge University Press, 464 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-64523-2

- Roosevelt, T. 1910. African game trails: an account of the African wanderings of an American hunter-naturalist. Scribner, 529 pp.

- Rundel, P.W., Smith, A.P. and Meinzer, F.C. 1994. Tropical alpine environments: plant form and function. Cambridge University Press, 376 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-42089-1