Kepler-7b is one of the first five exoplanets to be confirmed by NASA's Kepler spacecraft, and was confirmed during the first 34 days of Kepler's science operations.[2] It orbits a star slightly hotter and significantly larger than the Sun that is expected to soon reach the end of the main sequence.[2] Kepler-7b is a hot Jupiter that is about half the mass of Jupiter, but is nearly 1.5 times its size; at the time of its discovery, Kepler-7b was the second most diffuse planet known, surpassed only by WASP-17b.[2] It orbits its host star every five days at a distance of approximately 0.06 AU (9,000,000 km; 5,600,000 mi). Kepler-7b was announced at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society on January 4, 2010. It is the first extrasolar planet to have a crude map of cloud coverage.[7][8][9]

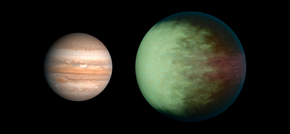

Size comparison of Kepler-7b with Jupiter, showing a rudimentary map of its atmosphere[1] derived from telescope observations | |

| Discovery[2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovery date | January 4, 2010[3] |

| Transit (Kepler Mission)[2] | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 0.06224 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0[2] |

| 4.885525±0.000040[2] d | |

| Inclination | 86.5[4] |

| Star | Kepler-7 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 1.478+0.050 −0.051[2] RJ | |

| Mass | 0.433+0.040 −0.041[2] MJ |

Mean density | 0.166+0.019 −0.020 g/cm3[citation needed] |

| Albedo | 0.32±0.03[5][6] |

| Temperature | 1,540 K (1,270 °C; 2,310 °F)[2] |

Characteristics

editMass, temperature, and orbit

editKepler-7b is a hot Jupiter, a Jupiter-like exoplanet orbiting close to its star. Its equilibrium temperature, due to its proximity to its star, is hot and is measured at nearly 1540 K. However, of the first five planets discovered by Kepler, it is the second coolest, being surpassed only by Kepler-6b.[4] This is over twelve times hotter than Jupiter.[4] Kepler-7b has a mass of only 0.433 that of Jupiter but due to proximity to its star the planet has expanded to a radius of 1.478 that of Jupiter. Because of this its mean density is only 0.166 g/cm3, about the same as expanded polystyrene. Only WASP-17b (0.49MJ; 1.66RJ)[10] was known to have a lower density at the time of Kepler-7b's discovery.[2] Such low densities are not predicted by current standard theories of planet formation.[11]

Kepler-7b orbits its host star every 4.8855 days at a distance of 0.06224 AU, making it the furthest-orbiting planet of the first five discovered by Kepler. Mercury, in contrast, orbits at a distance of 0.387 AU every 87.97 days.[12] In addition Kepler-7b has an observed orbital inclination of 86.5º, which means that its orbit is almost edge-on as seen from Earth.[4]

Cloud mapping

editAstronomers using data from NASA's Kepler and Spitzer space telescopes have created a cloud map of the planet. It is the first cloud map to be created beyond the Solar System. Kepler's visible-light observations of Kepler-7b's Moon-like phases led to a rough map of the planet that showed a bright spot on its western hemisphere.[13] But these data were not enough on their own to decipher whether the bright spot was coming from clouds or heat. The Spitzer Space Telescope played a crucial role in answering this question.[14] Jonathan Fortney, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz, said: "These clouds may well be composed of rock and iron, since the planet is over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius)." Brice-Olivier Demory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology noted that the oceans and continents cannot be detected, but a clear reflective signature has been detected which is interpreted as cloud. Thomas Barclay, Kepler scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center, said: "Unlike those on Earth, the cloud patterns on this planet do not seem to change much over time—it has a remarkably stable climate."[1]

Host star

editKepler-7 is the largest host star of the first five planets detected by Kepler, and is situated in the Lyra constellation. The star has a radius 184% that of the Sun. Kepler-7 also has 135% the Sun's mass, and thus is larger and more massive (though less dense) than the Sun. It is slightly hotter than the Sun, as Kepler-7 has an effective temperature of 5933 K.[15] The star is near the end of its life on the main sequence.[2] The star's metallicity is [Fe/H] = 0.11, which means that Kepler-7 has 128% the amount of iron than is detected in the Sun.[15]

Discovery

editIn 2009, NASA's Kepler space telescope was completing the last of tests on its photometer, the instrument it uses to detect transit events, in which a planet crosses in front of and dims its host star for a brief and roughly regular period of time. In this last test, Kepler observed 50000 stars in the Kepler Input Catalog, including Kepler-7; the preliminary light curves were sent to the Kepler science team for analysis, who chose obvious planetary companions from the bunch for follow-up at observatories. Kepler-7 was not one of these original candidates.[2] After a resting period of 1.3 days, Kepler began a nonstop 33.5-day period in which it observed 150000 targets uninterrupted until June 15, 2009, when the collected data was downloaded and tested for false positives. Kepler-7's candidate was not found to be one of these false positives, such as an eclipsing binary star that may generate a light curve that mimics that of transiting planetary companions.

Kepler-7 was then observed using Doppler spectroscopy using the Fibre-fed Echelle Spectrograph at the Canary Islands' Nordic Optical Telescope for ten nights in October 2009, taken regards to the star HD 182488 to compensate for possible telescope error. Speckle imaging of the star was taken at WIYN Observatory in Arizona to check for close companions; when none were found, the High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer instrument at the W.M. Keck Observatory on Hawaii, the Harlan J. Smith Telescope at the McDonald Observatory in Texas, the PRISM camera at the Lowell Observatory, and the Faulkes Telescope North at the Haleakala Observatory on Maui were also used to analyze Doppler spectroscopy of the planetary candidate.

The radial velocity observations confirmed that a planetary body was responsible for the dips observed in Kepler-7's light curve, thus confirming it as a planet.[2] Kepler's first discoveries, including the planets Kepler-4b, Kepler-5b, Kepler-6b, Kepler-7b, and Kepler-8b, were first announced on January 4, 2010, at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, D.C.[3] In May 2011, the planet was detected by brightness variations of the star cause by reflected starlight from the planet. It was found that Kepler-7b has a relatively high geometric albedo of 0.3.[16]

References

edit- ^ a b NASA/JPL (30 September 2013). "Astronomers find patchy clouds on exotic world". NASA. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Latham, David W.; et al. (2010). "Kepler-7b: A Transiting Planet with Unusually Low Density". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 713 (2): L140–L144. arXiv:1001.0190. Bibcode:2010ApJ...713L.140L. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/713/2/L140.

- ^ a b Ron Cowen (4 January 2010). "Kepler space telescope finds its first extrasolar planets". Science News. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Summary Table of Kepler Discoveries". NASA. 15 March 2010. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ Angerhausen, Daniel; DeLarme, Em; Morse, Jon A. (2015). "A Comprehensive Study of Kepler Phase Curves and Secondary Eclipses: Temperatures and Albedos of Confirmed Kepler Giant Planets". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 127 (957): 1113–1130. arXiv:1404.4348. Bibcode:2015PASP..127.1113A. doi:10.1086/683797. S2CID 118462488.

- ^ Heng, Kevin; Demory, Brice-Oliver (2013). "Understanding Trends Associated With Clouds In Irradiated Exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal. 777 (2): 100. arXiv:1309.5956. Bibcode:2013ApJ...777..100H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/777/2/100. S2CID 119298230.

- And errata in Heng, Kevin; Demory, Brice-Olivier (2014). "ERRATUM: "UNDERSTANDING TRENDS ASSOCIATED WITH CLOUDS IN IRRADIATED EXOPLANETS" (2013, ApJ, 777, 100)". The Astrophysical Journal. 785: 80. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/785/1/80.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney; Johnson, Michele; Cole, Steve (30 September 2013). "NASA Space Telescopes Find Patchy Clouds on Exotic World". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ Chu, Jennifer (2 October 2013). "Scientists generate first map of clouds on an exoplanet". MIT. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ Demory, Brice-Olivier; et al. (2013). "Inference of Inhomogeneous Clouds in an Exoplanet Atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 776 (2): L25. arXiv:1309.7894. Bibcode:2013ApJ...776L..25D. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/776/2/L25. S2CID 701011.

- ^ "The Planets". SuperWASP. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Henderson, Mark (5 January 2010). "Kepler telescope finds five new worlds". London: Timesonline. Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- ^ David Williams (17 November 2010). "Mercury Fact Sheet". Goddard Space Flight Center. NASA. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ Shporer, Avi; Hu, Renyu (2015), "Studying Atmosphere-Dominated Hot Jupiterkeplerphase Curves: Evidence That Inhomogeneous Atmospheric Reflection is Common", The Astronomical Journal, 150 (4): 112, arXiv:1504.00498, Bibcode:2015AJ....150..112S, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/150/4/112, S2CID 33182939

- ^ "NASA Space Telescopes Find Patchy Clouds on Exotic World". NASA. 30 September 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ a b Jean Schneider (2010). "Notes for star Kepler-6". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ Demory, Brice-Olivier; et al. (2011). "The High Albedo of the Hot Jupiter Kepler-7B". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 735 (1): L12. arXiv:1105.5143. Bibcode:2011ApJ...735L..12D. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/735/1/L12. S2CID 399287.

External links

edit- Media related to Kepler-7 b at Wikimedia Commons