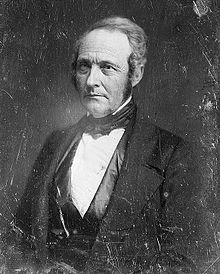

Jacob Collamer (January 8, 1791 – November 9, 1865) was an American politician from Vermont. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives, as Postmaster General in the cabinet of President Zachary Taylor, and as a U.S. Senator.

Jacob Collamer | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Vermont | |

| In office March 4, 1855 – November 9, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Lawrence Brainerd |

| Succeeded by | Luke P. Poland |

| Judge of the Vermont Circuit Court | |

| In office 1850–1854 | |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Abel Underwood |

| 13th United States Postmaster General | |

| In office March 8, 1849 – July 22, 1850 | |

| President | Zachary Taylor Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | Cave Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Nathan K. Hall |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Vermont's 2nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1849 | |

| Preceded by | William Slade |

| Succeeded by | William Hebard |

| Associate Justice of the Vermont Supreme Court | |

| In office 1833–1842 | |

| Preceded by | Nicholas Baylies |

| Succeeded by | William Hebard |

| State's Attorney of Windsor County | |

| In office 1820–1824 | |

| Preceded by | Asa Aikens |

| Succeeded by | Isaac Cushman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 8, 1791 Troy, New York, U.S. |

| Died | November 9, 1865 (aged 74) Woodstock, Vermont, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (Before 1854) Republican (1854–1865) |

| Spouse | Mary Stone |

| Children | 7 |

| Education | University of Vermont (AM) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | Vermont Militia |

| Years of service | 1812–1815 |

| Rank | First Lieutenant |

| Unit | 4th Regiment, Vermont Detached Militia Brigade 2nd Brigade, 4th Division |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 |

Born in Troy, New York, and raised in Burlington, Vermont, Collamer graduated from the University of Vermont, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1813. After service in the militia during the War of 1812, he became active as an attorney, first in Royalton, and then in Woodstock. Highly regarded in the legal profession, he became a respected prosecutor, legislator, and judge.

Elected to the House of Representatives in 1842, Collamer became a prominent Whig leader and advocate of the anti-slavery cause. President Taylor selected Collamer to serve as Postmaster General following the 1848 presidential election. Collamer served until shortly after Taylor's death when he resigned to allow Taylor's successor, Millard Fillmore, to name his own appointee.

Collamer was elected to the Senate as a Republican in 1855, shortly after the formation of the new party. He became a respected voice against slavery and a prominent supporter of the Lincoln administration during the American Civil War. An advocate of more stringent postwar Reconstruction measures than those that were favored by Lincoln and his successor, Andrew Johnson, Collamer advocated congressional control of the Reconstruction process. He died in Woodstock and was buried at River Street Cemetery in Woodstock.

Early life edit

Jacob Collamer was born in Troy, New York on January 8, 1791, the son of Samuel Collamer and Elizabeth (Van Arnum) Collamer, and his family moved to Burlington, Vermont in 1795.[1] He received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Vermont in 1810,[2] and after additional study, UVM later upgraded Collamer's degree to Master of Arts.[3][4][5] He studied law in St. Albans, Vermont with Asa Aldis, Asahel Langworthy, and Benjamin Swift.[6] He then relocated to Randolph, Vermont, where he completed his legal studies with attorney William Nutting,[7] and he was admitted to the bar in 1813.[6] During the War of 1812, Collamer was appointed a deputy U.S. tax collector for the district that included Orange County, Vermont, and was responsible for collecting levies in support of the war effort.[8]

Military service edit

He served as an officer in a Vermont Militia unit during the War of 1812.[9] Appointed as an ensign in the 4th Regiment commanded by William Williams,[10] he served first with an artillery unit on Vermont's border with Canada.[6] After promotion to first lieutenant, Collamer served as aide-de-camp to Brigadier General John French, commander of the militia's 2nd Brigade, 4th Division.[11][12]

French's unit left Orange County for upstate New York in September 1814 in response to warnings of an imminent British invasion from Canada.[6] When the brigade was crossing Lake Champlain en route to Plattsburgh, Collamer was sent ahead in a boat to inform Vermont Militia commander Samuel Strong that French's troops were on their way.[6] Collamer was fired on by American sentinels, but was uninjured.[6] Strong informed Collamer that the Battle of Plattsburgh had taken place the day before, and the British had retreated, so French's troops returned home.[6]

Early career edit

In 1816, he moved to Royalton, Vermont, where he continued to practice law.[6] He remained a resident of Royalton for 20 years, practicing law in partnership with James Barrett.[13] Among the prospective attorneys who studied law under his supervision was Lyman Gibbons, who later served as a justice of the Alabama Supreme Court.[14] Collamer also served in local offices, including Register of Probate, Windsor County State's Attorney, and member of the Vermont House of Representatives.[15] While serving in the House, Collamer was the main proponent of the legislation that created the Vermont Senate in 1836.[16]

From 1833 to 1842 Collamer was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of Vermont, succeeding Nicholas Baylies.[17][18] In 1836 he moved to Woodstock.[19] From 1839 to 1845 Collamer was a Trustee of the University of Vermont.[20]

House of Representatives edit

Elected to the US House of Representatives in 1842 as a Whig, Collamer served three terms, from 1843 to 1849.[21] He opposed the extension of slavery, the Texas Annexation, and the Mexican–American War; supported high tariffs to help American manufacturers and received national recognition for his "Wool and Woolens" speech on tariffs.[22][23]

Collamer was Chairman of the Committee on Manufactures (Twenty-eighth Congress) and the Committee on Public Lands (Thirtieth Congress).[24]

Postmaster General edit

Collamer served as Postmaster General under President Zachary Taylor. Appointed at the start of the Taylor's administration in 1849, he served until resigning in July 1850.[25] Collamer resigned shortly after Taylor's death to enable President Millard Fillmore to name his own appointee.[26]

As Postmaster General, Collamer was criticized by Whig partisans of the spoils system because he was reluctant to remove local Democratic postmasters en masse so they could be replaced by Whigs.[27] Among his accomplishments was the introduction of a permanent system for using postage stamps; Collamer sent the first letter using one, a note addressed to his brother in Barre, Vermont in which he recommended saving the stamp because if the system worked, it might be valuable to collectors.[28]

Beyond politics edit

Upon returning to Vermont, Collamer was appointed a judge of the newly-created state Circuit Court, where he served until 1854.[29] He was succeeded on the bench by Abel Underwood, who served until the state Circuit Court was abolished in an 1857 court reorganization.[30]

Collamer was a longtime trustee of and lecturer at the Vermont Medical College in Woodstock and served as President of the Board of Trustees.[31]

Senator edit

In 1855 Collamer was elected to the Senate as a conservative, anti-slavery Republican.[32] In his first term, Collamer was Chairman of the Committee on Engrossed Bills (Thirty-fourth Congress).[33]

In 1856, Collamer received several votes for Vice President at the Republican National Convention.[34]

In the Senate, he defended his positions vigorously even when he was in the minority.[35] When the Committee on Territories, chaired by Stephen A. Douglas, recommended passage of the Crittenden Amendment, which proposed resubmitting for popular vote the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution for Kansas, Collamer and James R. Doolittle of Wisconsin refused to vote in favor but instead crafted a persuasive minority report explaining their opposition.[36]

Collamer also represented the minority view in June 1860, when the select committee chaired by James Murray Mason issued its report on John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry.[37] Mason argued that Brown's raid was the work of an organized abolitionist movement, which needed to be curtailed with federal authority.[38] Collamer and Doolittle countered that Brown and his followers had been caught and punished and that further government action was not necessary.[38]

Collamer's years on the bench helped develop his reputation as the best lawyer in the Senate.[39] His colleagues were known to pay close attention to his remarks on the Senate floor even though he spoke infrequently and even then too quietly to reach the entire chamber or the galleries.[40] Charles Sumner referred to Collamer as the "Green-Mountain Socrates"[40] and called him the wisest and best balanced statesman of his time.[41]

Civil War edit

At the 1860 Republican National Convention, Collamer received the favorite son votes of Vermont's delegates and withdrew after the first ballot.[42] Reelected to the Senate in 1861, he served until his death.[43]

In 1861, Collamer authored the bill to invest the President with new war powers and give Congressional approval to the war measures that Abraham Lincoln had taken under his own authority at the start of his administration.[44]

Collamer was the lead senator of the nine Republicans who visited Lincoln in 1862 to argue for change in the composition of his cabinet by persuading him to replace his Secretary of State, William Henry Seward.[45] Having been encouraged to confront Lincoln by claims of cabinet disharmony from Lincoln's Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, the senators changed their minds during the meeting after Chase was maneuvered by Lincoln into backtracking on his initial argument.[46]

Again a member of the majority once the Democrats from the southern states left the Senate during the war, Collamer was Chairman of the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads (Thirty-seventh to Thirty-ninth Congresses) and the Committee on the Library (Thirty-eighth and Thirty-ninth Congresses).[47]

After the war, Collamer opposed the Reconstruction of plans of Presidents Lincoln and Andrew Johnson and was an advocate of Congressional control over the process of readmitting former Confederate states to the Union.[22]

Death edit

Collamer died at his home in Woodstock on November 9, 1865[21] and was buried in Woodstock's River Street Cemetery.[48][49]

Awards and honors edit

Collamer received the honorary degree of LL.D. from the University of Vermont in 1850 and Dartmouth College in 1855.[50]

In 1881, the state of Vermont donated a marble statue of Collamer created by Preston Powers to the U.S. Capitol's National Statuary Hall Collection.[51] Each state is represented by two statues, and Vermont's are likenesses of Collamer and Ethan Allen.[52][53]

Family edit

In 1817, Collamer married Mary Stone, who died in 1870.[54] Their children included Elisabeth, Harriet, Mary, Edward, Ellen, Frances, and William.[55]

Home edit

Collamer's home at 40 Elm Street in Woodstock is part of the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park's Civil War Home Front Walking Tour.[56][57]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Barrett, James (1868). Memorial Address on the Life and Character of the Hon. Jacob Collamer. Rutland, VT: Tuttle & Co. pp. 4–14.

- ^ "Commencement at Burlington". The Washingtonian. Windsor, VT. October 1, 1810. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bishop, Morris (1962). A History of Cornell. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780801455377.

- ^ Thayer, William Roscoe (1915). The Life And Letters Of John Hay. Vol. I. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 28.

- ^ Thompson, Zadock (1842). History Of Vermont, Natural, Civil And Statistical. Burlington, VT: Chauncey Goodrich. p. 149.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Memorial Address on the Life and Character of the Hon. Jacob Collamer, p. 4.

- ^ Nickerson & Cox (1895). The Illustrated Historical Souvenir of Randolph, Vermont. Randolph, VT: Nickerson & Cox. p. 19.

- ^ "Payment Notice by Collector Thomas Leverett". The Washingtonian. Windsor, VT. November 20, 1815. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ James V. Marshall, The United States Manual of Biography and History, 1856, page 613

- ^ "U.S. War of 1812 Service Records, 1812-1815, Entry for Jacob Collamer". Ancestry.com. Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com LLC. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ Child, Hamilton (1888). Gazetteer of Orange County, Vt., 1762-1888. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse Journal Company. pp. 128–129.

- ^ Vermont General Assembly (1816). Journals of the General Assembly of the State of Vermont. Montpelier, VT: Vermont Secretary of State. p. 147.

- ^ Taft, Russell Smith (July 1, 1901). "Hon. James Barrett". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. Boston, MA: New England Historical and Genealogical Society. p. 295.

- ^ Amherst College, Obituary Record: Roll of Graduates deceased during the Year 1879-1880; Deaths Not Previously Reported (1880), p. 187.

- ^ Memorial Address on the Life and Character of the Hon. Jacob Collamer, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Kelly, Mary Louise (1944). Jacob Collamer: Woodstock's U.S. Senator. Woodstock, VT: Woodstock Historical Society. p. 4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Memorial Address on the Life and Character of the Hon. Jacob Collamer, p. 5.

- ^ Thompson, Zadock (1842). History of Vermont, Natural, Civil and Statistical. Burlington, VT: Chauncey Goodrich. p. 124.

- ^ Tinkham, O. M. (July 1, 1900). "Jacob Collamer". The Vermonter. St. Albans, VT: Charles Spooner Forbes. p. 234.

- ^ University of Vermont, Catalogue of the University of Vermont, 1890, page 9

- ^ a b Memorial Address on the Life and Character of the Hon. Jacob Collamer, p. 12.

- ^ a b John J. Duffy, Samuel B. Hand, Ralph H. Orth, editors, The Vermont Encyclopedia, 2003, page 91

- ^ Memorial Address on the Life and Character of the Hon. Jacob Collamer, p. 13.

- ^ Memorial Address on the Life and Character of the Hon. Jacob Collamer, p. 14.

- ^ Marshall, James V. (1856). The United States Manual of Biography and History. Philadelphia, PA: James B. Smith & Co. p. 613.

- ^ McCook, Anson G. (1887). Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States. Vol. VIII. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 205.

- ^ K. Jack Bauer, Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest, 1993, page 262

- ^ Jacob Collamer: Woodstock's U.S. Senator, p. 4.

- ^ Charles C. Little and James Brown (Boston), The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge for the Year 1852, 1851, page 234

- ^ Child, Hamilton (1888). Gazetteer of Orange County, Vt., 1762-1888. Vol. Part 1. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse Journal Company. p. 113.

- ^ University of Vermont, University of Vermont Obituary Record, Volume 1, pages 23-24

- ^ Garrison, William Lloyd; Ruchames, Louis (1975). The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison: From Disunionism to the Brink of War. Vol. IV. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge, MA. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-674-52663-1.

- ^ Historian of the United States Senate (2015). "Chairmen of Senate Standing Committees, 1789-present" (PDF). senate.gov/. Washington, DC: U.S. Senate. pp. 20, 45, 54.

- ^ Republican National Committee, Proceedings of the First Three Republican National Conventions, 1893, pages 63-64

- ^ Jacob Collamer: Woodstock's U.S. Senator, p. 17.

- ^ Jacob Collamer: Woodstock's U.S. Senator, p. 20.

- ^ West Virginia Culture and History, Senate Select Committee Report on the Harper’s Ferry Invasion, retrieved December 17, 2013

- ^ a b "Mason Report". www.wvculture.org.

- ^ Bogue, Allan G. (2009). The Earnest Men: Republicans of the Civil War Senate. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0801475696.

- ^ a b The Earnest Men: Republicans of the Civil War Senate, p. 32.

- ^ Barber, A. D. (November 5, 1896). Vermont as a Leader in Educational Progress. Montpelier, VT: Vermont Historical Society. p. 107 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Vermonter magazine, Incidents in the Life of Lincoln, January 1909, page 5

- ^ William Lloyd Garrison, The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, 1976, page 397

- ^ Jacob G. Ullery, Men of Vermont Illustrated, 1894, pages 121-124

- ^ Chester G. Hearn, Lincoln, the Cabinet, and the Generals, 2010, pages 139-143

- ^ Hearn, Chester G. (28 March 2018). Lincoln, the Cabinet, and the Generals. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807137338 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chairmen of Senate Standing Committees, 1789-present.

- ^ U.S. Government Printing Office, Addresses on the Death of Senator Jacob Collamer, 1866, pages 61-62

- ^ Robert I. Vexler, The Vice-Presidents and Cabinet Members: Biographies Arranged Chronologically by Administration, Volume 1, 1975, page 185

- ^ University of Vermont, University of Vermont Obituary Record, Volume 1, 1895, pages 23-24

- ^ The Vermonter: Jacob Collamer, p. 238.

- ^ United States Congress, Joint Committee on the Library, Legislation Creating the National Statuary Hall in the Capitol, 1916, page 25

- ^ Glenn Brown, Glenn Brown's History of the United States Capitol, 1900, page 530

- ^ Reno, Conrad (1900). Memoirs of the Judiciary and the Bar of New England. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Century Memorial Publishing Co. p. 26.

- ^ Memoirs of the Judiciary and the Bar of New England, p. 26.

- ^ National Park Service, Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historic Park, Civil War Home Front Walking Tour, retrieved December 17, 2013

- ^ Patricia Harris and David Lyon, Boston Globe, Civil War History Still Breathes Down the Years, July 11, 2010

External links edit

- United States Congress. "Jacob Collamer (id: C000628)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Jacob Collamer at Find a Grave

-

The Zachary Taylor Administration, 1849 Daguerreotype by Mathew Brady

From left to right: William Ballard Preston, Thomas Ewing, John M. Clayton, Zachary Taylor, William M. Meredith, George W. Crawford, Jacob Collamer and Reverdy Johnson in 1849 -

Jacob Collamer in U.S Statuary Hall

-

Jacob Collamer during the Civil War