Gallium(III) chloride is an inorganic chemical compound with the formula GaCl3 which forms a monohydrate, GaCl3·H2O. Solid gallium(III) chloride is a deliquescent white solid and exists as a dimer with the formula Ga2Cl6.[2] It is colourless and soluble in virtually all solvents, even alkanes, which is truly unusual for a metal halide. It is the main precursor to most derivatives of gallium and a reagent in organic synthesis.[3]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Gallium trichloride, Trichlorogallium, Trichlorogallane

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.268 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| GaCl 3 | |

| Molar mass | 176.073 g/mol (anhydrous) 194.10 g/mol (monohydrate) |

| Appearance | colorless crystals |

| Density | 2.47 g/cm3 (anhydrous) |

| Melting point | 77.9 °C (172.2 °F; 351.0 K) (anhydrous) 44.4 °C (monohydrate) |

| Boiling point | 201 °C (394 °F; 474 K) (anhydrous) |

| very soluble | |

| Solubility | soluble in benzene, CCl4, CS2, and alkanes |

| −63.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure[1] | |

| monoclinic | |

| C2/m | |

a = 11.95 Å, b = 6.86 Å, c = 7.05 Å α = 90°, β = 125.7°, γ = 90°

| |

Lattice volume (V)

|

469 Å3 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H314 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

4700 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Gallium(III) fluoride Gallium(III) bromide Gallium(III) iodide |

Other cations

|

Aluminium chloride Indium(III) chloride Thallium(III) chloride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

As a Lewis acid, GaCl3 is milder than aluminium chloride. It is also easier to reduce than aluminium chloride. The coordination chemistry of Ga(III) and Fe(III) are similar, so gallium(III) chloride has been used as a diamagnetic analogue of ferric chloride.

Preparation

editGallium(III) chloride can be prepared from the elements by heating gallium metal in a stream of chlorine at 200 °C and purifying the product by sublimation under vacuum.[4][5]

- 2 Ga + 3 Cl2 → 2 GaCl3

It can also be prepared from by heating gallium oxide with thionyl chloride:[6]

- Ga2O3 + 3 SOCl2 → 2 GaCl3 + 3 SO2

Gallium metal reacts slowly with hydrochloric acid, producing hydrogen gas.[7] Evaporation of this solution produces the monohydrate.[8]

Structure

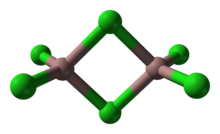

editAs a solid, it adopts a bitetrahedral structure with two bridging chlorides. Its structure resembles that of aluminium tribromide. In contrast AlCl3 and InCl3 feature contain 6 coordinate metal centers. As a consequence of its molecular nature and associated low lattice energy, gallium(III) chloride has a lower melting point vs the aluminium and indium trihalides. The formula of Ga2Cl6 is often written as Ga2(μ-Cl)2Cl4.[1]

In the gas-phase, the dimeric (Ga2Cl6) and trigonal planar monomeric (GaCl3) are in a temperature-dependent equilibrium, with higher temperatures favoring the monomeric form. At 870 K, all gas-phase molecules are effectively in the monomeric form.[9]

In the monohydrate, the gallium is tetrahedrally coordinated with three chlorine molecules and one water molecule.[8]

Properties

editPhysical

editGallium(III) chloride is a diamagnetic and deliquescent colorless white solid that melts at 77.9 °C and boils at 201 °C without decomposition to the elements. This low melting point results from the fact that it forms discrete Ga2Cl6 molecules in the solid state. Gallium(III) chloride dissolves in water with the release of heat to form a colorless solution, which when evaporated, produces a colorless monohydrate, which melts at 44.4 °C.[8][10][11]

Chemical

editGallium is the lightest member of Group 13 to have a full d shell, (gallium has the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p1) below the valence electrons that could take part in d-π bonding with ligands. The low oxidation state of Ga in Ga(III)Cl3, along with the low electronegativity and high polarisability, allow GaCl3 to behave as a "soft acid" in terms of the HSAB theory.[12] The strength of the bonds between gallium halides and ligands have been extensively studied. What emerges is:[13]

- GaCl3 is a weaker Lewis acid than AlCl3 towards N and O donors e.g. pyridine

- GaCl3 is a stronger Lewis acid than AlCl3 towards thioethers e.g. dimethyl sulfide, Me2S

With a chloride ion as ligand the tetrahedral GaCl4− ion is produced, the 6 coordinate GaCl63− cannot be made. Compounds like KGa2Cl7 that have a chloride bridged anion are known.[14] In a molten mixture of KCl and GaCl3, the following equilibrium exists:

- 2 GaCl4− ⇌ Ga2Cl7− + Cl−

When dissolved in water, gallium(III) chloride dissociates into the octahederal [Ga(H2O)6]3+ and Cl- ions forming an acidic solution, due to the hydrolysis of the hexaaquogallium(III) ion:[15]

- [Ga(H2O)6]3+ → [Ga(H2O)5OH]2+ + H+ (pKa = 3.0)

In basic solution, it hydrolyzes to gallium(III) hydroxide, which redissolves with the addition of more hydroxide, possibly to form Ga(OH)4-.[15]

Uses

editOrganic synthesis

editGallium(III) chloride is a Lewis acid catalyst, such as in the Friedel–Crafts reaction, which is able to substitute more common lewis acids such as ferric chloride. Gallium complexes strongly with π-donors, especially silylethynes, producing a strongly electrophilic complex. These complexes are used as an alkylating agent for aromatic hydrocarbons.[3]

It is also used in carbogallation reactions of compounds with a carbon-carbon triple bond. It is also used as a catalyst in many organic reactions.[3]

Organogallium compounds

editIt is a precursor to organogallium reagents. For example, trimethylgallium, an organogallium compound used in MOCVD to produce various gallium-containing semiconductors, is produced by the reaction of gallium(III) chloride with various alkylating agents, such as dimethylzinc, trimethylaluminium, or methylmagnesium iodide.[16][17][18]

Purification of gallium

editGallium(III) chloride is an intermediate in various gallium purification processes, where gallium(III) chloride is fractionally distilled or extracted from acid solutions.[7]

Detection of solar neutrinos

edit110 tons of gallium(III) chloride aqueous solution was used in the GALLEX and GNO experiments performed at Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso in Italy to detect solar neutrinos. In these experiments, germanium-71 was produced by neutrino interactions with the isotope gallium-71 (which has a natural abundance of 40%), and the subsequent beta decays of germanium-71 were measured.[10]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Sergey I. Troyanov; Thoralf Krahl; Erhard Kemnitz (2004). "Crystal structures of GaX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) and AlI3". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie - Crystalline Materials. 219 (2): 88–92. doi:10.1524/zkri.219.2.88.26320.

- ^ Wells, A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- ^ a b c Yamaguchi, Masahiko; Matsunaga, Shigeki; Shibasaki, Masakatsu; Michelet, Bastien; Bour, Christophe; Gandon, Vincent (2014), "Gallium Trichloride", Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–8, doi:10.1002/047084289x.rn00118u.pub3, ISBN 9780470842898

- ^ Roger A. Kovar; J. A. Dilts (1977). "Gallium Trichloride". Inorganic Syntheses Volume 17. McGraw‐Hill. pp. 167–172. ISBN 9780470131794.

- ^ Gray, Floyd (2013). "Gallium and Gallium Compounds". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0701121219010215.a01.pub3. ISBN 9780471238966.

- ^ H. Hecht; G. Jander; H. Schlapmann (1947). "Über die Einwirkung von Thionylchlorid auf Oxyde" [On the effect of thionyl chloride on oxides]. Zeitschrift für anorganische Chemie. 254 (5–6): 255–264. doi:10.1002/zaac.19472540501.

- ^ a b Greber, Jörg (2000). "Gallium and Gallium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_163. ISBN 9783527306732.

- ^ a b c Jacques Roziere; Marie-Thérèse Roziere-Bories; Alain Manteghetti; Antoine Potier (1974). "Hydrates des halogenures de gallium. II Spectroscopie de vibration des complexes coordinés GaX3•H2O (X = Cl ou Br)". Canadian Journal of Chemistry (in French). 52 (18): 3274–3280. doi:10.1139/v74-483.

- ^ Viacheslav I. Tsirelnikov; Boris V. Lokshin; Petr Melnikov; Valter A. Nascimento (2012). "On the Existence of the Trimer of Gallium Trichloride in the Gaseous Phase". Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie. 638 (14): 2335–2339. doi:10.1002/zaac.201200282.

- ^ a b David R. Lide, ed. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 85th Edition, Internet Version 2005. CRC Press, 2005.

- ^ J. Burgess; J. Kijowski (1981). "Enthalpies of solution of chlorides and iodides of gallium(III), indium(III), thorium(IV) and uranium(IV)". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 43 (11): 2649–2652. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(81)80592-1.

- ^ Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2018) [2001]. Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-1-292-13414-7.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 237–239. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Jens H. Von Barner (1985). "Potentiometric and Raman spectroscopic study of the complex formation of gallium(III) in potassium chloride-aluminum chloride melts at 300C". Inorganic Chemistry. 24 (11): 1686–1689. doi:10.1021/ic00205a019.

- ^ a b Scott A. Wood; Iain M. Samson (2006). "The aqueous geochemistry of gallium, germanium, indium and scandium". Ore Geology Reviews. 28 (1): 57–102. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2003.06.002.

- ^ Kraus, C. A.; Toonder, F. E. (1933). "Trimethyl Gallium, Trimethyl Gallium Etherate and Trimethyl Gallium Ammine". PNAS. 19 (3): 292–8. Bibcode:1933PNAS...19..292K. doi:10.1073/pnas.19.3.292. PMC 1085965. PMID 16577510.

- ^ Foster, Douglas F.; Cole-Hamilton, David J. (1997). "Electronic Grade Alkyls of Group 12 and 13 Elements". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 31. p. 29-66. doi:10.1002/9780470132623.ch7. ISBN 978-0-471-15288-0.

- ^ WO application 2014078263, Liam P. Spencer, James C. Stevens, Deodatta Vinayak Shenai-Khatkhate, "Methods of producing trimethylgallium", published 2014-05-22

Further reading

edit- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

External links

edit- "Emergency First Aid Treatment Guide - Gallium Trichloride". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 2004-11-12.