The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (March 2020) |

Environmental issues are disruptions in the usual function of ecosystems.[1] Further, these issues can be caused by humans (human impact on the environment)[2] or they can be natural. These issues are considered serious when the ecosystem cannot recover in the present situation, and catastrophic if the ecosystem is projected to certainly collapse.

Environmental protection is the practice of protecting the natural environment on the individual, organizational or governmental levels, for the benefit of both the environment and humans. Environmentalism is a social and environmental movement that addresses environmental issues through advocacy, legislation education, and activism.[3]

Environment destruction caused by humans is a global, ongoing problem.[4] Water pollution also cause problems to marine life.[5] Most scholars think that the project peak global world population of between 9-10 billion people, could live sustainably within the earth's ecosystems if human society worked to live sustainably within planetary boundaries.[6][7][8] The bulk of environmental impacts are caused by excessive consumption of industrial goods by the world's wealthiest populations.[9][10][11] The UN Environmental Program, in its "Making Peace With Nature" Report in 2021, found addressing key planetary crises, like pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss, was achievable if parties work to address the Sustainable Development Goals.[12]

Types edit

Major current environmental issues may include climate change, pollution, environmental degradation, and resource depletion. The conservation movement lobbies for protection of endangered species and protection of any ecologically valuable natural areas, genetically modified foods and global warming. The UN system has adopted international frameworks for environmental issues in three key issues, which has been encoded as the "triple planetary crises": climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss.[13]

Human impact edit

- Top-left: Satellite image of Southeast Asian haze.

- Top-right: IAEA experts investigate the Fukushima disaster.

- Middle-left: a picture from 1997 of industrial fishing, a practice that has led to overfishing.

- Middle-right: a seabird during an oil spill.

- Bottom-left: Acid mine drainage in the Rio Tinto.

- Bottom-right: depiction of deforestation of Brazil's Atlantic forest by Portuguese settlers, c. 1820–25.

Human impact on the environment (or anthropogenic environmental impact) refers to changes to biophysical environments[14] and to ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural resources[15] caused directly or indirectly by humans. Modifying the environment to fit the needs of society (as in the built environment) is causing severe effects[16][17] including global warming,[14][18][19] environmental degradation[14] (such as ocean acidification[14][20]), mass extinction and biodiversity loss,[21][22][23] ecological crisis, and ecological collapse. Some human activities that cause damage (either directly or indirectly) to the environment on a global scale include population growth,[24][25][26] neoliberal economic policies[27][28][29] and rapid economic growth,[30] overconsumption, overexploitation, pollution, and deforestation. Some of the problems, including global warming and biodiversity loss, have been proposed as representing catastrophic risks to the survival of the human species.[31][32]

The term anthropogenic designates an effect or object resulting from human activity. The term was first used in the technical sense by Russian geologist Alexey Pavlov, and it was first used in English by British ecologist Arthur Tansley in reference to human influences on climax plant communities.[33] The atmospheric scientist Paul Crutzen introduced the term "Anthropocene" in the mid-1970s.[34] The term is sometimes used in the context of pollution produced from human activity since the start of the Agricultural Revolution but also applies broadly to all major human impacts on the environment.[35][36][37] Many of the actions taken by humans that contribute to a heated environment stem from the burning of fossil fuel from a variety of sources, such as: electricity, cars, planes, space heating, manufacturing, or the destruction of forests.[38]Degradation edit

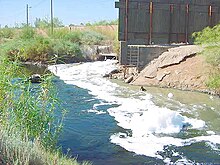

Environmental degradation is the deterioration of the environment through depletion of resources such as quality of air, water and soil; the destruction of ecosystems; habitat destruction; the extinction of wildlife; and pollution. It is defined as any change or disturbance to the environment perceived to be deleterious or undesirable.[39][40] The environmental degradation process amplifies the impact of environmental issues which leave lasting impacts on the environment.[41]

Environmental degradation is one of the ten threats officially cautioned by the High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change of the United Nations. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction defines environmental degradation as "the reduction of the capacity of the environment to meet social and ecological objectives, and needs".[42]

Environmental degradation comes in many types. When natural habitats are destroyed or natural resources are depleted, the environment is degraded; direct environmental degredation, such as deforestation which has readily visible; this can be caused by more indirect process, such as the build up of plastic pollution over time or the buildup of greenhouse gases that causes tipping points in the climate system. Efforts to counteract this problem include environmental protection and environmental resources management. Mismanagement that leads to degradation can also lead to environmental conflict where communities organize in opposition to the forces that mismanaged the environment.Conflict edit

Environmental conflicts, socio-environmental conflict or ecological distribution conflicts (EDCs) are social conflicts caused by environmental degradation or by unequal distribution of environmental resources.[43][44][45] The Environmental Justice Atlas documented 3,100 environmental conflicts worldwide as of April 2020 and emphasised that many more conflicts remained undocumented.[43]

Parties involved in these conflicts include locally affected communities, states, companies and investors, and social or environmental movements;[46][47] typically environmental defenders are protecting their homelands from resource extraction or hazardous waste disposal.[43] Resource extraction and hazardous waste activities often create resource scarcities (such as by overfishing or deforestation), pollute the environment, and degrade the living space for humans and nature, resulting in conflict.[48] A particular case of environmental conflicts are forestry conflicts, or forest conflicts which "are broadly viewed as struggles of varying intensity between interest groups, over values and issues related to forest policy and the use of forest resources".[49] In the last decades, a growing number of these have been identified globally.[50]

Frequently environmental conflicts focus on environmental justice issues, the rights of indigenous people, the rights of peasants, or threats to communities whose livelihoods are dependent on the ocean.[43] Outcomes of local conflicts are increasingly influenced by trans-national environmental justice networks that comprise the global environmental justice movement.[43][51]

Environmental conflict can complicate response to natural disaster or exacerbate existing conflicts – especially in the context of geopolitical disputes or where communities have been displaced to create environmental migrants.[52][45][48] The study of these conflicts is related to the fields of ecological economics, political ecology, and environmental justice.Costs edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2016) |

Action edit

Justice edit

Environmental justice or eco-justice, is a social movement to address environmental injustice, which occurs when poor or marginalized communities are harmed by hazardous waste, resource extraction, and other land uses from which they do not benefit.[53][54] The movement has generated hundreds of studies showing that exposure to environmental harm is inequitably distributed.[55]

The movement began in the United States in the 1980s. It was heavily influenced by the American civil rights movement and focused on environmental racism within rich countries. The movement was later expanded to consider gender, international environmental injustice, and inequalities within marginalised groups. As the movement achieved some success in rich countries, environmental burdens were shifted to the Global South (as for example through extractivism or the global waste trade). The movement for environmental justice has thus become more global, with some of its aims now being articulated by the United Nations. The movement overlaps with movements for Indigenous land rights and for the human right to a healthy environment.[56]

The goal of the environmental justice movement is to achieve agency for marginalised communities in making environmental decisions that affect their lives. The global environmental justice movement arises from local environmental conflicts in which environmental defenders frequently confront multi-national corporations in resource extraction or other industries. Local outcomes of these conflicts are increasingly influenced by trans-national environmental justice networks.[57][58]

Environmental justice scholars have produced a large interdisciplinary body of social science literature that includes contributions to political ecology, environmental law, and theories on justice and sustainability.[54][59][60]The 2023 IPCC report highlighted the disproportionate effects of climate change on vulnerable populations. The report's findings make it clear that every increment of global warming exacerbates challenges such as extreme heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and other weather extremes, which in turn amplify risks for human health and ecosystems. With nearly half of the world's population residing in regions highly susceptible to climate change, the urgency for global actions that are both rapid and sustained is underscored. The importance of integrating diverse knowledge systems, including scientific, Indigenous, and local knowledge, into climate action is highlighted as a means to foster inclusive solutions that address the complexities of climate impacts across different communities.[61]

In addition, the report points out the critical gap in adaptation finance, noting that developing countries require significantly more resources to effectively adapt to climate challenges than what is currently available. This financial disparity raises questions about the global commitment to equitable climate action and underscores the need for a substantial increase in support and resources. The IPCC's analysis suggests that with adequate financial investment and international cooperation, it is possible to embark on a pathway towards resilience and sustainability that benefits all sections of society.[61]

Law edit

Assessment edit

Environmental Impact assessment (EIA) is the assessment of the environmental consequences of a plan, policy, program, or actual projects prior to the decision to move forward with the proposed action. In this context, the term "environmental impact assessment" is usually used when applied to actual projects by individuals or companies and the term "strategic environmental assessment" (SEA) applies to policies, plans and programmes most often proposed by organs of state.[65][66] It is a tool of environmental management forming a part of project approval and decision-making.[67] Environmental assessments may be governed by rules of administrative procedure regarding public participation and documentation of decision making, and may be subject to judicial review.

The purpose of the assessment is to ensure that decision-makers consider the environmental impacts when deciding whether or not to proceed with a project. The International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) defines an environmental impact assessment as "the process of identifying, predicting, evaluating and mitigating the biophysical, social, and other relevant effects of development proposals prior to major decisions being taken and commitments made".[68] EIAs are unique in that they do not require adherence to a predetermined environmental outcome, but rather they require decision-makers to account for environmental values in their decisions and to justify those decisions in light of detailed environmental studies and public comments on the potential environmental impacts.[69]Movement edit

The environmental movement (sometimes referred to as the ecology movement) is a social movement that aims to protect the natural world from harmful environmental practices in order to create sustainable living.[70] Environmentalists advocate the just and sustainable management of resources and stewardship of the environment through changes in public policy and individual behavior.[71] In its recognition of humanity as a participant in (not an enemy of) ecosystems, the movement is centered on ecology, health, as well as human rights.

The environmental movement is an international movement, represented by a range of environmental organizations, from enterprises to grassroots and varies from country to country. Due to its large membership, varying and strong beliefs, and occasionally speculative nature, the environmental movement is not always united in its goals. At its broadest, the movement includes private citizens, professionals, religious devotees, politicians, scientists, nonprofit organizations, and individual advocates like former Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson and Rachel Carson in the 20th century.Organizations edit

Environmental issues are addressed at a regional, national or international level by government organizations.

The largest international agency, set up in 1972, is the United Nations Environment Programme. The International Union for Conservation of Nature brings together 83 states, 108 government agencies, 766 Non-governmental organizations and 81 international organizations and about 10,000 experts, scientists from countries around the world.[72] International non-governmental organizations include Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth and World Wide Fund for Nature. Governments enact environmental policy and enforce environmental law and this is done to differing degrees around the world.

Film and television edit

There are an increasing number of films being produced on environmental issues, especially on climate change and global warming. Al Gore's 2006 film An Inconvenient Truth gained commercial success and a high media profile.

See also edit

- Citizen science

- Ecotax

- Environmental impact statement

- Index of environmental articles

- Triple planetary crisis

Issues

- List of environmental issues (includes mitigation and conservation)

Specific issues

- Environmental impact of agriculture

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Environmental impact of reservoirs

- Environmental impact of the energy industry

- Environmental impact of fishing

- Environmental impact of irrigation

- Environmental impact of mining

- Environmental impact of paint

- Environmental impact of paper

- Environmental impact of pesticides

- Environmental implications of nanotechnology

- Environmental impact of shipping

- Environmental impact of war

References edit

- ^ Jhariya et al. 2022. "Natural Resources Conservation and Advances for Sustainability" Chapter 7.5 ISBN 978-0-12-822976-7

- ^ "Human Impacts on the Environment". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ Eccleston, Charles H. (2010). Global Environmental Policy: Concepts, Principles, and Practice. Chapter 7. ISBN 978-1439847664.

- ^ McNeill, Z. Zane (2022-09-07). "Humans Destroying Ecosystems: How to Measure Our Impact on the Environment". Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ "Marine Pollution". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ Alberro, Heather (28 January 2020). "Why we should be wary of blaming 'overpopulation' for the climate crisis". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ^ "David Attenborough's claim that humans have overrun the planet is his most popular comment". www.newstatesman.com. 4 November 2020. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ^ "Dominic Lawson: The population timebomb is a myth The doom-sayers are becoming more fashionable just as experts are coming to the view it has all been one giant false alarm". The Independent. UK. 18 January 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Nässén, Jonas; Andersson, David; Larsson, Jörgen; Holmberg, John (2015). "Explaining the Variation in Greenhouse Gas Emissions Between Households: Socioeconomic, Motivational, and Physical Factors". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 19 (3): 480–489. Bibcode:2015JInEc..19..480N. doi:10.1111/jiec.12168. ISSN 1530-9290. S2CID 154132383.

- ^ Moser, Stephanie; Kleinhückelkotten, Silke (2017-06-09). "Good Intents, but Low Impacts: Diverging Importance of Motivational and Socioeconomic Determinants Explaining Pro-Environmental Behavior, Energy Use, and Carbon Footprint". Environment and Behavior. 50 (6): 626–656. doi:10.1177/0013916517710685. ISSN 0013-9165. S2CID 149413363.

- ^ Lynch, Michael J.; Long, Michael A.; Stretesky, Paul B.; Barrett, Kimberly L. (2019-05-15). "Measuring the Ecological Impact of the Wealthy: Excessive Consumption, Ecological Disorganization, Green Crime, and Justice". Social Currents. 6 (4): 377–395. doi:10.1177/2329496519847491. ISSN 2329-4965. S2CID 181366798.

- ^ Environment, U. N. (2021-02-11). "Making Peace With Nature". UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ^ "SDGs will address 'three planetary crises' harming life on Earth". UN News. 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ^ a b c d Wuebbles DJ, Fahey DW, Hibbard KA, DeAngelo B, Doherty S, Hayhoe K, Horton R, Kossin JP, Taylor PC, Waple AM, Weaver CP (2017). "Executive Summary". In Wuebbles DJ, Fahey DW, Hibbard KA, Dokken DJ, Stewart BC, Maycock TK (eds.). Climate Science Special Report – Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4). Vol. I. Washington, DC: U.S. Global Change Research Program. pp. 12–34. doi:10.7930/J0DJ5CTG.

- ^ Sahney, Benton & Ferry (2010); Hawksworth & Bull (2008); Steffen et al. (2006) Chapin, Matson & Vitousek (2011)

- ^ Stockton, Nick (22 April 2015). "The Biggest Threat to the Earth? We Have Too Many Kids". Wired.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R. (5 November 2019). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:1808/30278. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

Still increasing by roughly 80 million people per year, or more than 200,000 per day (figure 1a–b), the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity. There are proven and effective policies that strengthen human rights while lowering fertility rates and lessening the impacts of population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss. These policies make family-planning services available to all people, remove barriers to their access and achieve full gender equity, including primary and secondary education as a global norm for all, especially girls and young women (Bongaarts and O'Neill 2018).

- ^ Cook, John (13 April 2016). "Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming". Environmental Research Letters. 11 (4): 048002. Bibcode:2016ERL....11d8002C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002. hdl:1983/34949783-dac1-4ce7-ad95-5dc0798930a6.

The consensus that humans are causing recent global warming is shared by 90%–100% of publishing climate scientists according to six independent studies

- ^ Lenton, Timothy M.; Xu, Chi; Abrams, Jesse F.; Ghadiali, Ashish; Loriani, Sina; Sakschewski, Boris; Zimm, Caroline; Ebi, Kristie L.; Dunn, Robert R.; Svenning, Jens-Christian; Scheffer, Marten (2023). "Quantifying the human cost of global warming". Nature Sustainability. 6 (10): 1237–1247. Bibcode:2023NatSu...6.1237L. doi:10.1038/s41893-023-01132-6. hdl:10871/132650.

- ^ "Increased Ocean Acidity". Epa.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 30 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

Carbon dioxide is added to the atmosphere whenever people burn fossil fuels. Oceans play an important role in keeping the Earth's carbon cycle in balance. As the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere rises, the oceans absorb a lot of it. In the ocean, carbon dioxide reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid. This causes the acidity of seawater to increase.

- ^ Leakey, Richard and Roger Lewin, 1996, The Sixth Extinction : Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind, Anchor, ISBN 0-385-46809-1

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Barnosky, Anthony D.; Garcia, Andrés; Pringle, Robert M.; Palmer, Todd M. (2015). "Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction". Science Advances. 1 (5): e1400253. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0253C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400253. PMC 4640606. PMID 26601195.

- ^ Pimm, S. L.; Jenkins, C. N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T. M.; Gittleman, J. L.; Joppa, L. N.; Raven, P. H.; Roberts, C. M.; Sexton, J. O. (30 May 2014). "The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection" (PDF). Science. 344 (6187): 1246752. doi:10.1126/science.1246752. PMID 24876501. S2CID 206552746. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

The overarching driver of species extinction is human population growth and increasing per capita consumption.

- ^ Crist, Eileen; Ripple, William J.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Rees, William E.; Wolf, Christopher (2022). "Scientists' warning on population" (PDF). Science of the Total Environment. 845: 157166. Bibcode:2022ScTEn.845o7166C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157166. PMID 35803428. S2CID 250387801.

- ^ Perkins, Sid (11 July 2017). "The best way to reduce your carbon footprint is one the government isn't telling you about". Science. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ Nordström, Jonas; Shogren, Jason F.; Thunström, Linda (15 April 2020). "Do parents counter-balance the carbon emissions of their children?". PLOS One. 15 (4): e0231105. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1531105N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231105. PMC 7159189. PMID 32294098.

It is well understood that adding to the population increases CO2 emissions.

- ^ Harvey, David (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0199283279.

- ^ Rees, William E. (2020). "Ecological economics for humanity's plague phase" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 169: 106519. Bibcode:2020EcoEc.16906519R. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106519. S2CID 209502532.

the neoliberal paradigm contributes significantly to planetary unraveling. Neoliberal thinking treats the economy and the ecosphere as separate independent systems and essentially ignores the latter.

- ^ Jones, Ellie-Anne; Stafford, Rick (2021). "Neoliberalism and the Environment: Are We Aware of Appropriate Action to Save the Planet and Do We Think We Are Doing Enough?". Earth. 2 (2): 331–339. Bibcode:2021Earth...2..331J. doi:10.3390/earth2020019.

- ^ Cafaro, Philip (2022). "Reducing Human Numbers and the Size of our Economies is Necessary to Avoid a Mass Extinction and Share Earth Justly with Other Species". Philosophia. 50 (5): 2263–2282. doi:10.1007/s11406-022-00497-w. S2CID 247433264.

Conservation biologists agree that humanity is on the verge of causing a mass extinction and that its primary driver is our immense and rapidly expanding global economy.

- ^ "New Climate Risk Classification Created to Account for Potential "Existential" Threats". Scripps Institution of Oceanography. 14 September 2017. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

A new study evaluating models of future climate scenarios has led to the creation of the new risk categories "catastrophic" and "unknown" to characterize the range of threats posed by rapid global warming. Researchers propose that unknown risks imply existential threats to the survival of humanity.

- ^ Torres, Phil (11 April 2016). "Biodiversity loss: An existential risk comparable to climate change". Thebulletin.org. Taylor & Francis. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Bampton, M. (1999) "Anthropogenic Transformation" Archived 22 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine in Encyclopedia of Environmental Science, D. E. Alexander and R. W. Fairbridge (eds.), Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, ISBN 0412740508.

- ^ Crutzen, Paul and Eugene F. Stoermer. "The 'Anthropocene'" in International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme Newsletter. 41 (May 2000): 17–18

- ^ Scott, Michon (2014). "Glossary". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ Syvitski, Jaia; Waters, Colin N.; Day, John; et al. (2020). "Extraordinary human energy consumption and resultant geological impacts beginning around 1950 CE initiated the proposed Anthropocene Epoch". Communications Earth & Environment. 1 (32): 32. Bibcode:2020ComEE...1...32S. doi:10.1038/s43247-020-00029-y. hdl:10810/51932. S2CID 222415797.

- ^ Elhacham, Emily; Ben-Uri, Liad; et al. (2020). "Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass". Nature. 588 (7838): 442–444. Bibcode:2020Natur.588..442E. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5. PMID 33299177. S2CID 228077506.

- ^ Trenberth, Kevin E. (2 October 2018). "Climate change caused by human activities is happening and it already has major consequences". Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law. 36 (4): 463–481. Bibcode:2018JENRL..36..463T. doi:10.1080/02646811.2018.1450895. ISSN 0264-6811. S2CID 135104338.

- ^ Johnson, D. L.; Ambrose, S. H.; Bassett, T. J.; Bowen, M. L.; Crummey, D. E.; Isaacson, J. S.; Johnson, D. N.; Lamb, P.; Saul, M.; Winter-Nelson, A. E. (1 May 1997). "Meanings of Environmental Terms". Journal of Environmental Quality. 26 (3): 581–589. Bibcode:1997JEnvQ..26..581J. doi:10.2134/jeq1997.00472425002600030002x.

- ^ Yeganeh, Kia Hamid (1 January 2020). "A typology of sources, manifestations, and implications of environmental degradation". Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal. 31 (3): 765–783. Bibcode:2020MEnvQ..31..765Y. doi:10.1108/MEQ-02-2019-0036.

- ^ "Environmental Degradation - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2024-03-08.

- ^ "ISDR : Terminology". The International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. 2004-03-31. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ a b c d e Scheidel, Arnim; Del Bene, Daniela; Liu, Juan; Navas, Grettel; Mingorría, Sara; Demaria, Federico; Avila, Sofía; Roy, Brototi; Ertör, Irmak; Temper, Leah; Martínez-Alier, Joan (2020-07-01). "Environmental conflicts and defenders: A global overview". Global Environmental Change. 63: 102104. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102104. ISSN 0959-3780. PMC 7418451. PMID 32801483.

- ^ Lee, James R. (2019-06-12). "What is a field and why does it grow? Is there a field of environmental conflict?". Environmental Conflict and Cooperation. Routledge. pp. 69–75. doi:10.4324/9781351139243-9. ISBN 978-1-351-13924-3. S2CID 198051009.

- ^ a b Libiszewski, Stephan (1991). "What is an Environmental Conflict?" (PDF). Journal of Peace Research. 28 (4): 407–422.

- ^ Cardoso, Andrea (December 2015). "Behind the life cycle of coal: Socio-environmental liabilities of coal mining in Cesar, Colombia". Ecological Economics. 120: 71–82. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.10.004.

- ^ Orta-Martínez, Martí; Finer, Matt (December 2010). "Oil frontiers and indigenous resistance in the Peruvian Amazon". Ecological Economics. 70 (2): 207–218. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.022.

- ^ a b Mason, Simon; Spillman, Kurt R (2009-11-17). "Environmental Conflicts and Regional Conflict Management". WELFARE ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT – Volume II. EOLSS Publications. ISBN 978-1-84826-010-8.

- ^ Hellström, Eeva (2001). Conflict cultures: qualitative comparative analysis of environmental conflicts in forestry. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Society of Forest Science [and] Finnish Forest Research Institute. ISBN 951-40-1777-3. OCLC 47207066.

- ^ Mola-Yudego, Blas; Gritten, David (October 2010). "Determining forest conflict hotspots according to academic and environmental groups". Forest Policy and Economics. 12 (8): 575–580. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2010.07.004.

- ^ Martinez Alier, Joan; Temper, Leah; Del Bene, Daniela; Scheidel, Arnim (2016). "Is there a global environmental justice movement?". Journal of Peasant Studies. 43 (3): 731–755. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1141198. S2CID 156535916.

- ^ "Environment, Conflict and Peacebuilding". International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ^ Size, Julie; London, Jonathan K. (July 2008). "Environmental Justice at the Crossroads". Sociology Compass. 2 (4): 1331–1354. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00131.x.

- ^ a b Schlosberg 2007, p. [page needed].

- ^ Malin, Stephanie (June 25, 2019). "Environmental justice and natural resource extraction: intersections of power, equity and access". Environmental Sociology. 5 (2): 109–116. Bibcode:2019EnvSo...5..109M. doi:10.1080/23251042.2019.1608420. S2CID 198588483.

- ^ Martinez-Alier 2002, p. [page needed].

- ^ Scheidel, Arnim (July 2020). "Environmental conflicts and defenders: A global overview". Global Environmental Change. 63: 102104. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102104. PMC 7418451. PMID 32801483.

- ^ Martinez-Alier, Joan; Temper, Leah; Del Bene, Daniela; Scheidel, Arnim (3 May 2016). "Is there a global environmental justice movement?". The Journal of Peasant Studies. 43 (3): 731–755. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1141198. S2CID 156535916.

- ^ Miller, G. Tyler Jr. (2003). Environmental Science: Working With the Earth (9th ed.). Pacific Grove, California: Brooks/Cole. p. G5. ISBN 0-534-42039-7.

- ^ Sze, Julie (2018). Sustainability: Approaches to Environmental Justice and Social Power. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-9456-7.[page needed]

- ^ a b "Urgent climate action can secure a liveable future for all — IPCC". Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ Phillipe Sands (2003) Principles of International Environmental Law. 2nd Edition. p. xxi Available at [1] Accessed 19 February 2020

- ^ "What is Environmental Law? | Becoming an Environmental Lawyer". Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ "NOUN | National Open University of Nigeria". nou.edu.ng. Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- ^ MacKinnon, A. J., Duinker, P. N., Walker, T. R. (2018). The Application of Science in Environmental Impact Assessment. Routledge.

- ^ Eccleston, Charles H. (2011). Environmental Impact Assessment: A Guide to Best Professional Practices. Chapter 5. ISBN 978-1439828731

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 227.

- ^ "Principle of Environmental Impact Assessment Best Practice" (PDF). International Association for Impact Assessment. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ Holder, J., (2004), Environmental Assessment: The Regulation of Decision Making, Oxford University Press, New York; For a comparative discussion of the elements of various domestic EIA systems, see Christopher Wood Environmental Impact Assessment: A Comparative Review (2 ed, Prentice Hall, Harlow, 2002).

- ^ McCormick, John (1991). Reclaiming Paradise: The Global Environmental Movement. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20660-2. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Hawkins, Catherine A. (2010). "Sustainability, human rights, and environmental justice: Critical connections for contemporary social work". Critical Social Work. 11 (3). doi:10.22329/csw.v11i3.5833. ISSN 1543-9372. S2CID 211405454. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "About". IUCN. 2014-12-03. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

Works cited edit

- Chapin, F. Stuart; Matson, Pamela A.; Vitousek, Peter (September 2, 2011). Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-9504-9. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- Hawksworth, David L.; Bull, Alan T. (2008). Biodiversity and Conservation in Europe. Springer. p. 3390. ISBN 978-1402068645.

- Martinez-Alier, Joan (2002). The Environmentalism of the Poor. doi:10.4337/9781843765486. ISBN 978-1-84376-548-6.

- Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J.; Ferry, P.A. (2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land". Biology Letters. 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204. PMID 20106856.

- Steffen, Will; Sanderson, Regina Angelina; Tyson, Peter D.; Jäger, Jill; Matson, Pamela A.; Moore III, Berrien; Oldfield, Frank; Richardson, Katherine; Schellnhuber, Hans-Joachim (January 27, 2006). Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-26607-5. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- Schlosberg, David (2007). Defining Environmental Justice. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199286294.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-928629-4.

Further reading edit

- Ferguson, Robert (1999). Environmental Public Awareness Handbook: Case Studies and Lessons Learned in Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar: DSConsulting. ISBN 99929-50-13-7.

External links edit

- Media related to Environmental problems at Wikimedia Commons