The Eclogues (/ˈɛklɒɡz/; Latin: Eclogae [ˈɛklɔɡae̯]), also called the Bucolics, is the first of the three major works[1] of the Latin poet Virgil.

Background edit

Taking as his generic model the Greek bucolic poetry of Theocritus, Virgil created a Roman version partly by offering a dramatic and mythic interpretation of revolutionary change at Rome in the turbulent period between roughly 44 and 38 BC. Virgil introduced political clamor largely absent from Theocritus' poems, called idylls ("little scenes" or "vignettes"), even though erotic turbulence disturbs the "idyllic" landscapes of Theocritus.

Virgil's book contains ten pieces, each called not an idyll but an eclogue ("selection", "extract"),[2] populated by and large with herdsmen imagined conversing and performing amoebaean singing in rural settings, whether suffering or embracing revolutionary change or happy or unhappy love. Performed with great success on the Roman stage, they feature a mix of visionary politics and eroticism that made Virgil a celebrity in his own lifetime.

Like all of Virgil's works, the Eclogues are composed in dactylic hexameter.

Structure and organization edit

Several scholars have attempted to identify the organizational principles underpinning the construction of the book.[3][4] Most commonly the structure has been seen to be symmetrical, turning around eclogue 5, with a triadic pattern. The following scheme comes from Steenkamp (2011):[5]

- 1 – Confiscation of land

- 2 – Love song

- 3 – Singing contest

- 4 – Religion and the world that will be

- 5 – The 'pastor' becomes a god

- 6 – Mythology and the world that was

- 7 – Singing contest

- 8 – Two love songs

- 9 – Confiscation of land

The tenth eclogue stands alone, summing up the whole collection.

Numerous verbal echoes between the corresponding poems in each half reinforce the symmetry: for example, the phrase "Plant pears, Daphnis" in 9.50 echoes "Plant pears, Meliboeus" in 1.73.[6] Eclogue 10 has verbal echoes with all the earlier poems.[7][8] Thomas K. Hubbard (1998) has noted, "The first half of the book has often been seen as a positive construction of a pastoral vision, whilst the second half dramatizes progressive alienation from that vision, as each poem of the first half is taken up and responded to in reverse order."[9]

However, the arrangement of the eclogues into three groups of three does not prevent the collection also being seen as divided at the same time into two halves, with a second opening at the beginning of eclogue 6.[10]

The average length of each eclogue is 83 lines, but some are a little longer and some shorter. It has been observed that long and short poems alternate. Thus the 3rd eclogue in each half is the longest, while the 2nd and 4th are the shortest:[11]

- 1 – 83 lines

- 2 – 73

- 3 – 111

- 4 – 63

- 5 – 90

- 6 – 86 lines

- 7 – 70

- 8 – 108

- 9 – 67

- 10 – 77

Variety is also achieved by alternating dialogue eclogues (1, 3, 5, 7, 9) with monologues (2, 4, 6, 8, 10).

Some scholars have also observed numerical coincidences, when each eclogue in poems 1–9 is added to its pair: eclogues 2 + 8 = 3 + 7 = 181 lines, while eclogues 1 + 9 = 4 + 6 = 150/149 lines; 2 + 10 also = 150 lines. However, the significance of these findings is not clear.[12] Similar numerical phenomena have been found in other authors. For example, in Tibullus book 2, poems 1 + 6 = 2 + 5 = 3 + 4 = 144 lines.[13]

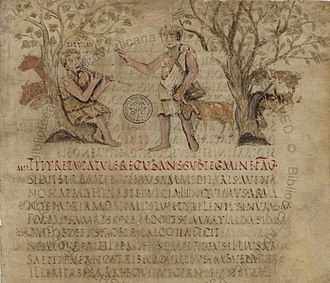

Eclogue 1 edit

A dialogue between Tityrus and Meliboeus. In the turmoil of the era Meliboeus has been forced off his land and faces an uncertain future. Tityrus recounts his journey to Rome and the "god" he met there who answered his plea and allowed him to remain on his land. He offers to let Meliboeus spend the night with him. This text has been viewed as reflecting the infamous land-confiscations after the return of Mark Antony and Octavian's joint forces from the Battle of Philippi of 42 BCE, in which Brutus and Cassius (the orchestrators of Caesar's assassination in 44 BCE) were defeated.[14]

Eclogue 2 edit

A monologue by the herdsman Corydon bemoaning his unrequited love for the handsome boy Alexis (the boss's darling) in the height of summer. The poem is adapted from the eleventh Idyll of Theocritus, in which the Cyclops Polyphemus laments the cruelty of the sea-nymph Galatea.

Eclogue 3 edit

Menalcas comes across a herdsman Damoetas, who is herding some animals on behalf of a friend. The two men exchange insults and then Damoetas challenges Menalcas to a singing competition. Menalcas accepts the challenge, offering some decorated cups as a prize, but Damoetas insists that the prize must be a calf, which is more valuable. A neighbour Palaemon agrees to judge the contest. The second half of the poem is the contest itself, ending with Palaemon pronouncing it a tie.

The eclogue is mostly based on Theocritus's Idyll 5, but with elements added from other idylls.

Eclogue 4 edit

Eclogue 4, also called the Messianic Eclogue,[15] imagines a golden age ushered in by the birth of a boy heralded as "great increase of Jove" (magnum Iovis incrementum). The poet makes this notional scion of Jove the occasion to predict his own metabasis up the scale in epos, rising from the humble bucolic to the lofty range of the heroic, potentially rivaling Homer: he thus signals his own ambition to make Roman epic that will culminate in the Aeneid. In the surge of ambition, Virgil also predicts defeating the legendary poet Orpheus and his mother, the epic muse Calliope, as well as Pan, the inventor of the bucolic pipe, even in Pan's homeland of Arcadia, which Virgil will claim as his own at the climax of his book in the tenth eclogue.

Identification of the fourth eclogue's child has proved elusive, but one common solution is that it refers to the predicted child of the sister of Octavian, Octavia the Younger, who had married Mark Antony in 40 BC.[16] The poem is dated to 40 BC by the reference to the consulship of Gaius Asinius Pollio, Virgil's patron at the time, to whom the eclogue is addressed.

In later years, it was often assumed that the boy predicted in the poem was Christ. The connection is first made in the Oration of Constantine[17] appended to the Life of Constantine by Eusebius of Caesarea (a reading to which Dante makes fleeting reference in his Purgatorio). Some scholars have also noted similarities between the eclogue's prophetic themes and the words of Isaiah 11:6: "a little child shall lead".

Eclogue 5 edit

In Eclogue 5, Menalcas, meeting the young goatherd Mopsus, flatters him and begs him to sing one of his songs. Mopsus is persuaded, and sings a song he has made mourning the death of the fabled herdsman Daphnis. After praising the song, Menalcas responds by singing a song of equal length describing the reception of Daphnis in heaven as a god. Mopsus praises Menalcas in turn, and the two exchange gifts.

Eclogue 5 articulates another significant pastoral theme, the shepherd-poet's concern with achieving worldly fame through poetry. Ensuring poetic fame is a fundamental interest of the shepherds in classical pastoral elegies, including the speaker in Milton's "Lycidas".[18]

Eclogue 6 edit

This eclogue tells the story of how two boys, Chromis and Mnasyllos, and a Naiad persuaded Silenus to sing to them, and how he sang to them of the world's beginning, the Flood, the Golden Age, Prometheus, Hylas, Pasiphaë, Atalanta and Phaëthon's sisters; after which he described how the Muses gave Gallus (a close personal friend of Virgil's) Hesiod's reed pipe and commissioned him to write a didactic poem; after which he told of Scylla (whom Virgil identifies as both the sea monster and the daughter of Nisos who was transmuted into a seabird) and of Tereus and Philomela, and then we learn that he has in fact been singing a song composed by Apollo on the banks of the Eurotas.

Eclogue 7 edit

The goatherd Meliboeus, a recurring character, soliloquizing remembers how he happened to be present at a great singing match between Corydon and Thyrsis. He then quotes from memory their actual songs (six rounds of matching quatrains) and recalls that Daphnis as judge declared Corydon the winner. This eclogue is based on pseudo-Theocritus Idyll VIII, though there the quatrains are not in hexameters but in elegiac couplets. Scholars argue about why Thyrsis loses. The reader may feel that despite the very close parallelism of his quatrains with Corydon's, they are less musical and sometimes cruder in content.

Eclogue 8 edit

This eclogue is also known as Pharmaceutria ("Sorceress"). The poet reports the contrasting songs of two herdsmen whose music is as powerful as that of Orpheus. Both songs are dramatic (the character in the first being a man and in the second a woman), both have almost the same pattern of three-to-five-line stanzas, with a refrain after each one. In one song the singer complains that his girlfriend is marrying another man; in the second a woman performs a magic spell to get her lover back.

Eclogue 9 edit

Young Lycidas meets old Moeris on his way to town and learns that Moeris's master, the poet Menalcas, has been evicted from his small farm and nearly killed. They proceed to recall snatches of Menalcas's poetry, two translated from Theocritus and two relating to contemporary events. Lycidas is anxious for a singing-match, while admitting that he is no match for two contemporary Roman poets whom he mentions by name, but Moeris pleads for forgetfulness and loss of voice. They walk on towards the city, postponing the competition until Menalcas arrives.

Eclogue 10 edit

In Eclogue 10, Virgil replaces Theocritus' Sicily and old bucolic hero, the impassioned oxherd Daphnis, with the impassioned voice of his contemporary Roman friend, the elegiac poet Gaius Cornelius Gallus, imagined dying of love in Arcadia. Virgil transforms this remote, mountainous, and myth-ridden region of Greece, homeland of Pan, into the original and ideal place of pastoral song, thus founding a richly resonant tradition in western literature and the arts.

This eclogue is the origin of the phrase omnia vincit amor ("love conquers all").

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Davis, Gregson (2010). "Introduction". Virgil's Eclogues, trans. Len Krisak. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-8122-4225-6

- ^ Liddell, Scott, Jones, Greek Lexicon έκλογή

- ^ Rudd, Niall (1976). Lines of Enquiry: Studies in Latin Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 119.

- ^ Clausen, Wendell (1994). Virgil: Eclogues. Clarendon, Oxford University Press. p. xxi. ISBN 0-19-815035-0.

- ^ Steenkamp, J. (2011). "The structure of Vergil's Eclogues". In Acta Classica: Proceedings of the Classical Association of South Africa (Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 101-124). Classical Association of South Africa (CASA); p. 113.

- ^ Steenkamp (2011), pp. 104–110.

- ^ Steenkamp (2011), p. 114.

- ^ Brooks Otis (1964) also detects a symmetry, in that eclogues 2, 3, 7 and 8 are particularly based on Theocritan models: Otis B. (1964), Vergil: A Study in Civilized Poetry (Oxford), pp. 128–31.

- ^ Hubbard, Thomas K. (1998). The Pipes of Pan: Intertextuality and Literary Filiation in the Pastoral Tradition from Theocritus to Milton. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-472-10855-8

- ^ Steenkamp (2011), p. 112.

- ^ Van Sickle, J. (1980). "The book-roll and some conventions of the poetic book". Arethusa, 13(1), 5–42; p. 20.

- ^ Steenkamp (2011), p. 113.

- ^ Dettmer, H. (1980). "The arrangement of Tibullus Books 1 and 2". Philologus, 124(1–2), 68–82; page 78.

- ^ Meban, David (2009). "Virgil's "Eclogues" and Social Memory". The American Journal of Philology. 130 (1): 99–130. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 20616169.

- ^ Edward Carpenter (1920) Pagan and Christian Creeds. p. 137.

- ^ Nisbet, R. G. M. (1995). Review of W V Clausen, A Commentary on Virgil, Eclogues. The Journal of Roman Studies, 85, 320-321; p. 320.

- ^ Oration of Constantine

- ^ Lee, Guy, trans. (1984). "Eclogue 5". In Virgil, The Eclogues. New York: Penguin. pp. 29–35.

Further reading edit

- Buckham, Philip Wentworth; Spence, Joseph; Holdsworth, Edward; Warburton, William; Jortin, John, Miscellanea Virgiliana: In Scriptis Maxime Eruditorum Virorum Varie Dispersa, in Unum Fasciculum Collecta, Cambridge: Printed for W. P. Grant; 1825.

- Coleman, Robert, ed. (1977). Vergil: Eclogues. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29107-0.

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 733.

- Hornblower, Simon; Antony Spawforth (1999). The Oxford Classical Dictionary: Third Edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- Hunter, Richard, ed. (1999). Theocritus: A Selection. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57420-X.

- Van Sickle, John B. (2004). The Design of Virgil's Bucolics. Duckworth. ISBN 1-85399-676-9.

- Van Sickle, John B. (2011). Virgil's Book of Bucolics, the Ten Eclogues in English Verse. Framed by Cues for Reading Out-Loud and Clues for Threading Texts and Themes. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9799-3.|

External links edit

In English

- The Eclogues, translated by John Dryden at Standard Ebooks

- The Eclogues public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- The Bucolics and Eclogues by Virgil at Project Gutenberg (in English)

- The Eclogues (translated by H.R. Fairclough for the Loeb Classical Library)

In Latin

- The Eclogues (Internet Classics Archive)

- The Bucolics and Eclogues by Virgil at Project Gutenberg (in Latin)

Other translations

Other links