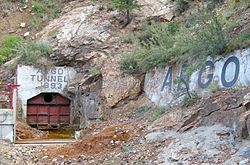

The Argo Tunnel is a 4.16-mile (6.69 km) mine drainage and access tunnel with its portal at Idaho Springs, Colorado, USA. It was originally called the Newhouse Tunnel after its primary investor, Salt Lake City mining magnate Samuel Newhouse, and appears by that name in many industry publications from the time period when it was constructed. The tunnel intersected nearly all the major gold mines between Idaho Springs and Central City, and is the longest such drainage tunnel in the Central City-Idaho Springs mining district.

Argo Tunnel | |

Argo Tunnel in 2009 | |

| Location | 2517 Riverside Dr., Idaho Springs, Colorado |

|---|---|

| Area | 20 acres (8.1 ha) |

| Built | 1893 |

| Architect | Multiple |

| NRHP reference No. | 78000836[1] |

| CSRHP No. | 5CC.76[2] |

| Added to NRHP | January 31, 1978 |

The mines along the Argo Tunnel are no longer active or maintained, but continue to exfiltrate ground water. The drainage from the tunnel was a major source of pollution in Clear Creek, until the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began treating it with a facility, built near the tunnel entrance. Large drainage tunnels in other mining districts include the Sutro Tunnel on the Comstock Lode in Nevada, and the Leadville Tunnel and the Yak Tunnel at Leadville, Colorado.

The associated gold ore mill is open to public tours. As of 2017, the tunnel's front portal was re-opened to the public and included on the tour circuit.

History

editThe Argo Tunnel was started from its southern terminus at Idaho Springs in September 1893, and reached its final length of 4.16 miles (6.69 km) in November 1910, after several pauses in the work. The actual time spent driving the tunnel was nine years and seven months. The tunnel intersected nearly all the major mines between Idaho Springs and Central City.[3]

The tunnel was built on an incline of one-half percent, so that water from the intersected mine workings would drain out the entrance at Idaho Springs rather than needing to be pumped out. In addition, loaded ore cars from the mines could benefit from gravity as they were trammed downhill to the tunnel entrance and then returned uphill as empties. Previously, ore from the mines was hoisted out of the vertical shafts and trucked to railroad sidings or mills. The tunnel was driven in a north-northwest direction, perpendicular to the predominant orientation of the gold veins. It was hoped that the tunnel would intersect previously undiscovered gold veins, but there is no record that important new ore bodies were discovered.

The tunnel operated until January 1943, when miners attempting to construct access and drainage for the Kansas Lode mine group near Nevadaville critically weakened a wall between the Argo and a flooded mine works. The section was holding back water at a later-estimated pressure of 500 psi (approximately 1,155 feet of hydraulic head), and a large slug of water was ejected through the tunnel and out the entrance, killing the four miners at the blasting site. A fifth person near the portal suspected trouble when the lights suddenly failed and ran for the entrance, narrowly escaping. Water was ejected for several hours.[4][5]

Due to preparations for World War II, the federal government ordered all gold mines in the US to shut down shortly before the accident occurred, intending that the workers and mining resources should be available for metals considered more essential to the war effort.[6] The Argo Tunnel never reopened.

Environmental remediation

editThe Argo Tunnel continued to drain acid water from the mines, and was recognized as a major continuing source of dissolved metals in Clear Creek. In May 1980, a surge of water flowed from the tunnel and turned the water in Clear Creek orange for some distance downstream. The temporary large increase in flow was attributed to a roof collapse somewhere within the tunnel damming a large volume of water behind it, then failing suddenly.[7]

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency listed the tunnel as part of the Central City/Clear Creek federal Superfund site in 1983, and built a treatment system at the mouth to neutralize and remove heavy metals from the 700-US-gallon (2,600 L) per minute acid mine drainage flow from the Argo, as well as lesser flows diverted to the plant from three other nearby mineworks, before it flows into Clear Creek.[8] The treatment system began operation in 1998.[9] The water treatment plant is just west of the old ore mill. A later modification to the tunnel included a high-pressure bulkhead installed roughly 200 feet inside of the portal entrance, enabling flow variations to be buffered inside the tunnel.

References

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Colorado State Register of Historic Properties – Clear Creek County". History Colorado. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Rens E. Schirmer, "The Argo, or Newhouse Tunnel," Mining and Engineering World, 1 May 1915, p.805.

- ^ "Argo Tunnel flood traps four and one body is recovered," Denver Post, 19 Jan. 1943, p.1.

- ^ "Argo Tunnel and Mill Tour: History," accessed 2019-10-21, http://argomilltour.com/history-of-the-argo/

- ^ Craig, James R; Rimstidt, J.Donald (1998). "Gold production history of the United States". Ore Geology Reviews. 13 (6): 407. doi:10.1016/S0169-1368(98)00009-2.

- ^ Peggy Strain, "Clear Creek's orange...'no health threat'," Denver Post, 22 May 1980.

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Central City/Clear Creek Archived August 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Superfund Site: Central City, Clear Creek, Idaho Springs, CO". Superfund Site Profile. EPA. Retrieved 2017-06-06.