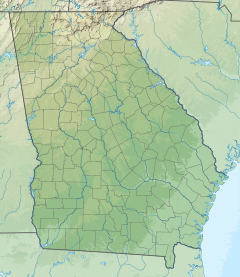

Acorn Creek is a stream in Carroll County in the U.S. state of Georgia, at an elevation of 666 feet (203 m) above mean sea level.[1][2] It is a tributary to the Chattahoochee River with a discharge rate of 2.74 cfs.[2][3]

| Acorn Creek | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| County | Carroll County, Georgia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • coordinates | 33°30′45″N 84°56′20″W / 33.5126123°N 84.9388292°W |

| Mouth | |

• coordinates | 33°27′10″N 84°58′25″W / 33.4528915°N 84.9735517°W |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Chattahoochee River |

| Basin features | |

| cities | Whitesburg, Georgia Acorn Town (extinct) |

Etymology

editAcorn Creek takes its name from Acorn Town, a Creek Indian settlement and plantation which stood near its mouth.[2] The original Muskogee name for this stream was Lakcv-hache.[4] The plantation was home to Chief McIntosh of the Lower Creek indigenous peoples, and was known by various names: Acorn Town, Acorn Bluff, and Lochau Talofau.[5]

History

editAcorn Creek today is located near the boundary of the McIntosh Reserve, a 527-acre (2.13 km2) outdoor recreation area operated by the Carroll County Recreation Department. Carroll County acquired Lochau Talofau and established the Reserve in 1978.[6] The Reserve contains a portion, but not all, of the larger 19th-century plantation of Acorn Bluff.[6][7][8]

The Reserve is named for William McIntosh, a prominent Creek Indian leader and planter who maintained a home and plantation at the site. McIntosh named his plantation Lochau Talofau, which in English means Acorn Bluff (less frequently Acorn Town) and was one square mile in size, encompassing the lower reaches of Acorn Creek.[5][8][9] At Acorn Bluff, McIntosh constructed a simple two-story log house which he used as both a residence and as an inn for travelers. A replica of the house was constructed after the purchase of the Reserve, and is open to park visitors.[10][11]

McIntosh and the Lower Creek tribes sided with the United States government (against the British and their Red Stick Creek allies) in the Creek War of 1813–1814. McIntosh distinguished himself in the battles of Autossee and Horseshoe Bend, and was promoted to the rank of Brigadier-General.[12][13] He again fought beside General Andrew Jackson in the First Seminole War of 1816-1819. A hero to many, McIntosh provoked the wrath of his fellow Creeks when he signed the second Treaty of Indian Springs, in 1825. The treaty essentially sold all Creek lands in Georgia and Alabama to the United States government. McIntosh was allowed to keep his plantation in exchange for signing the treaty. The sale of ancestral lands was opposed by the Creek National Council, which saw the act as both unauthorized and illegal. The Treaty of the Creek Agency (1818), which previously ceded two smaller portions of Creek lands, had moved the council to propose the execution of McIntosh. While McIntosh survived that earlier confrontation with the Creek National Council, the treaty of 1825 was his undoing. The Council ruled that McIntosh and other signatories had committed a capital offense against the Creek government and people by ceding communal lands, and ordered their execution.[14] McIntosh was murdered at his home, Acorn Bluff, in 1825.[14] McIntosh's grave is located in the McIntosh Reserve, adjacent to his reconstructed home.[10] Georgia Historical Marker 022-3 (1984) marks the location of Brigadier-General McIntosh's home and burial site.[12]

Geology and watershed

editThe stream originates just west of the city of Whitesburg, Georgia and empties into the Chattahoochee River in Carroll County.[2][15] The Acorn Creek-Chattahoochee River watershed has a total area of 28,284 acres.[16] The Acorn Creek-Chattahoochee River watershed is part of the larger Middle Chattahoochee-Lake Harding watershed which has an area of 1,950,182 acres.[16]

In Carroll County, where Acorn Creek flows into the path of the Chattahoochee river, the scar of the Brevard Fault is visible.[17] The fault is a geologic feature that spans several states.[17][18] From Atlanta to eastern Alabama, an area which includes Acorn Creek, the rock units that characterize the fault outcrop in widths rarely exceeding 600 feet (180 meters) yet extend along strike for 80 miles (130 km).[17][18] The Chattahoochee, at McIntosh Reserve, becomes a shallow shoal. A guide to that area notes "The rugged landscape is evidence of the Brevard Fault zone, so prominent along [this] section of the river".[19] The fault line is delineated where the banks of the Chattahoochee are "studded with huge boulders [which] rise 80 feet above the river".[19] Within a few miles, downstream of Acorn Creek, the Brevard Fault leaves the Chattahoochee River and "continues in a south-westerly direction into Alabama".[19]

McIntosh Reserve Park was closed for several months in 2009 and 2010, following the September 2009 flooding along the Chattahoochee River corridor and Acorn Creek.[20] The park reopened Memorial Day weekend, 2010.

Environmental assessment

editAn environmental assessment of the creek, performed in 1987-88 by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources - Environmental Protection Division (EPD) concluded that summer fecal coliform levels from both point and nonpoint pollution sources were within total maximum daily load target levels and no additional reductions were required.[21]

The stream is a popular fishing location. One online fishing site lists Shoal bass as the most popular species of fish caught in Acorn Creek.[22]

References

edit- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Acorn Creek; "Acorn Creek, Carroll County, Georgia". MyTopo.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- ^ Geological Survey Water-supply Paper. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1955. p. 362.

- ^ Richard L. Thornton (December 11, 2019). "What is the Latin word for water doing in a Muskogee-Creek dictionary?". ApalacheResearch.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Marjory Rutherford (March 14, 1961). "McIntosh Had Many Faces". Atlanta Constitution. p. 10. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "McIntosh Reserve". Carroll County Parks and Recreation. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Robert H. Mohlenbrock (April 2019). "McIntosh Reserve". Natural History. Archived from the original on 2020-07-16.

- ^ a b "Our History". City of Carrollton. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ James Leitch Wright (1 January 1986). Creeks & Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People. U of Nebraska Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-8032-9728-9.; Horace Montgomery (1 June 2010). Georgians in Profile: Historical Essays in Honor of Ellis Merton Coulter. University of Georgia Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8203-3547-6.

- ^ a b "McIntosh Reserve". Carroll County Historical Society. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Winston Skinner (January 1, 2019). "Historical markers illuminate Coweta's heritage". The Newnan Times-Herald. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Carroll County Historical Markers - McIntosh Reserve". GeorgiaInfo - The Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Griffith (1998), McIntosh and Weatherford, p. 1

- ^ a b Michael D. Green, The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis, University of Nebraska Press, 1985, pp. 96-97, accessed 14 September 2011

- ^ "Acorn Creek Topo Map". TopoZone. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b "History Of Construction For Existing CCR Surface Impoundment - Plant Yates Ash Pond B" (PDF). Georgia Power. 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c Fred Brown; Sherri M. L. Smith; Richard Stenger (2007). The Riverkeeper's Guide to the Chattahoochee. University of Georgia Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-58072-000-7.

- ^ a b Jack H. Medlin; Thomas J. Crawford (1973). "Stratigraphy And Structure Along The Brevard Fault Zone In Western Georgia And Eastern Alabama" (PDF). American Journal of Science. p. 100. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Fred Brown; Sherri M. L. Smith; Richard Stenger (2007). The Riverkeeper's Guide to the Chattahoochee. University of Georgia Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-58072-000-7.

- ^ Anthony J. Gotvald (2010). "Historic Flooding in Georgia, 2009". US Geological Survey. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ "Fecal Coliform TMDL Development - Acorn Creek (Creek Watershed), Chattahoochee River Basin". Georgia Department of Natural Resources - Environmental Protection Division. February 19, 1998. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "Acorn Creek". Fishbrain. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

Further reading

edit- Green, Michael D. The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1982 ISBN 978-0-803-27015-2

- Griffith, Jr., Benjamin W. McIntosh and Weatherford, Creek Indian Leaders, Birmingham: University of Alabama Press, 1998 ISBN 978-0-817-30914-5