Andrew J. Orr and Dickinson W. Orr, typically advertising as A. J. & D. W. Orr, were brothers, merchants, planters, railroad contractors, and slave traders based in Macon, Georgia, United States. The Orrs were originally from the Charlotte, North Carolina area, but moved to central Georgia early in their lives and remained there, first working as local merchants and then transitioning into the interstate slave trade, buying in the Carolinas and Richmond, Virginia, and selling to planters in the vicinity of Macon and Augusta, Georgia. They then became railroad contractors as well, using groups of enslaved men to build three separate Georgia railroad lines. A. J. Orr was beaten to death by a slave in 1855. D. W. Orr continued working as a railroad contractor until at least 1863. He died in 1867.

A. J. Orr | |

|---|---|

A. J. Orr classified ads 1849 to 1850 | |

| Born | c. 1815 North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | July 25, 1855 Near Hinesville, Liberty County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Occupation | Slave trader |

D. W. Orr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 1, 1819 |

| Died | October or November 1867 Near Griffin, Spalding County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Occupation | Slave trader |

Early lives and careers

editThe Orr brothers were natives of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, which has Charlotte as its county seat.[1][2] A. J. Orr was born about 1815,[3] and D. W. Orr was born in 1819.[4] D. W. Orr came to Georgia "when he was quite young" and made it his home for the rest of his life.[4] During the 1844 U.S. presidential election, the Orr brothers opposed the candidacy of Henry Clay.[5] By 1843, when they were in their 20s, the Orrs were partners in a retail shop at the corner of Cotton Avenue and Cherry Street in Macon, Georgia,[6] from which they sold hardware, dry goods, clothing, accessories, and shoes.[7] D. W. Orr also had some kind of business in Columbus, Georgia, where $3,000 worth of property was destroyed in October 1846 in a fire that leveled almost six square blocks.[8]

In 1846, D. W. Orr wrote a letter to South Carolina planter and slave trader John Springs III:[9]

[M]y brother has charge of the mercantile business at home and I have been engaged the majority of my time for twelve mos [months] in the purchase and sale of Negroes. It is my business here [Richmond, Virginia] at present. I have purchased nearly all I want and will leave for Macon in a few days...We can borrow money at home or in NCa at a much lower rate of interest at six mos but in the business in which I am engaged you are aware that their [sic] is times that Negroes are slow sale and I dont want to be placed in a situation to have to force sales to meet our notes.... I think you know our general character to[o] well to have any fears on the subject and I will here remark that you are the only person that we have offered more than common interest. [9]

In 1847 D. W. Orr purchased a 31-year-old enslaved preacher named Ralph R. Watson, who was originally from Louisa County, Virginia.[10] According to Watson's biography, "He labored in Virginia till 1847, when he was sold for debt. He was bought by Mr. D. W. Orr, who carried him to Macon, Georgia."[10] D. W. Orr was a registered guest of the Powhatan House hotel in Richmond, Virginia on February 19 and 20, 1847.[11] In the summer of 1847, the brothers Orr decided they were done with retailing dry goods and clothing, and announcing they were selling their inventory "at cost" in order to get out of the business hastily.[12] The following January, they wrote Springs that the reason for the sale was "to enable us to give our exclusive attention to the Negro trade, and we have sold this winter about sixty Negroes."[13] Springs continued funding the Orrs' trading ventures until at least 1849.[13] In May 1848, D. W. Orr placed a runaway slave ad in the Augusta Daily Constitutionalist that indicated the Orrs had been buying in Richmond, and had ties to Augusta, Georgia and the Hamburg, South Carolina slave market immediately across the Savannah River, which was used until 1856 as a means to circumvent Georgia's anti-slave trading law.[14]

Ran away from the Subscriber at the United States Hotel, in this city, 17th inst., a Negro fellow named JOHN, of dark yellow complexion, 5 feet, 6 or 8 inches high, stout built, weighing about 170 lbs., a Shoemaker by trade, dressed in a blue Kentucky Jeans coat with pickets on the outside. He came from Richmond, Virginia, and it is supposed be will go in that direction. The above reward will be paid for his apprehension and delivery to Messrs. Trowbridge & Cureton, Hamburg, So. Ca., or half the above reward will be paid for his confinement in any Jail in Georgia or Carolina so that I may get him. D. W. ORR at Macon Ga.

in 1850, D. W. Orr was a resident of Richmond, Virginia, where he shared a household with fellow slave trader Silas Omohundro.[15] Their nearest neighbor was slave trader Hector Davis.[16] A. J. Orr was one of three residents of Macon at the time of the 1850 U.S. federal census who listed their occupation as "negro trader," along with Robert Beasley and Joseph Cooper.[17] Orr reported that he owned $4,000 in property.[3] Orr seemingly ran a "negro house" on Cotton Avenue in Macon circa 1849–1850,[16] and frequently advertised specific people he had for sale, including a "valuable blacksmith," a "superior tanner and currier," and a "number-one Meat, Bread, and Pastry Cook, she can make Pickles, Preserves, &c." One individual sold during this time was nine-year-old Fanny, sold to Travis Huff, a landowner in the vicinity of Macon, for $400 on April 13, 1850; a later dispute over Fanny's "soundness" as a slave would result in lawsuit that went to the Georgia Supreme Court.[18] On the day of the census, August 13, 1850, A. J. Orr was the legal owner of 17 people, the oldest being a 33-year-old man, the youngest being a one-year-old baby girl.[19] By September 1850, however, the Orrs had left that location and another firm was advertising "100 Negroes for Sale" at the "old stand of Messrs. A. J. & D. W. Orr."[20] The following year, the Orrs were again advertising that they had a "negro mart" at a store in Macon, specifically "the building next to Messrs. Field & Adam's Fire-Proof Warehouse, where can be found at all times a choice lot of likely young Negroes for sale."[21]

As property-owning white males, the Orrs were legally permitted to participate in democratic processes in Georgia, such as in 1852 when D. W. Orr served on the Bibb County grand jury.[22] The same year, the Orrs sued Bibb County for the cash value of 26 "certificates or orders, drawn by the Clerks of the Superior and Inferior Courts of Bibb County, on the Treasurer thereof, in favor of various Jurors therein named, and payable to the Juror or bearer, and amounting in the aggregate to the sum of $264.92."[23] D. W. Orr served on the Bibb County grand jury again in 1855.[24]

D. W. Orr married Lizzie Slappy, daughter of Uriah Slappy, on February 19, 1852.[4]

For a period ending August 1, 1854, the South-Western Railroad Company paid $2,489.03 to A. J. & D. W. Orr.[25] Another one of the railroad contractors paid that year was a Reuben H. Slappy.[25]

Sally of Richmond, Virginia

editIn April 1853, D. W. Orr was apparently buying people in Richmond, as the newspaper mentioned him in a police docket item about the legal status of a woman named Sally. A report in the Richmond Dispatch stated, "Sally, an aged free negress, slave to Mrs John Wade, was arrested for going at large without a pass, on Sunday evening last. Mr. Hill stated that he sold the woman to D. W. Orr for $35 without warranty of soundness of mind, on the 20th instant. Since then, Mr O. believing that Sally was insane, refused to keep her or to pay the $35, and she has been wandering to and fro in our streets until arrested by the police."[26] Sally was put in a jail until her legal owner could be identified and held responsible for her.[26] The following day the Dispatch reiterated the facts to that time and reported, "Captain Wilkinson stated, that on two several occasions the watch found Sally sitting on the side walk and took her to the cage."[27] Orr was ordered to pay $100 bail guaranteeing his future appearance in the court on the matter.[27]

Killing of A. J. Orr

editOn July 25, 1855,[28] A. J. Orr was brutally murdered, apparently by a recaptured escaped slave, while Orr was working as a "railroad contractor" for the Savannah, Albany, and Gulf Railroad.[29] Railroad contractor in this context meant he had "ninety hands (negroes) in his employ."[30] These were likely chain gangs of slaves clearing the right-of-way and laying ties and track, although it's unclear who legally owned the workers. The murder of Orr is poorly documented, with the majority of detail found in Charleston and Savannah newspapers. The Charleston Courier reported on the discovery of Orr's body on August 1, 1855:[31]

The body of A. J. Orr of Macon, a contractor on the Savannah and Albany Rail Road was found on Sunday morning about eight miles from Hinesville where he had been most brutally murdered. It appears that a negro belonging to Mr. Orr had been ran away for some time and had been arrested and lodged in jail in this State whither Mr. Orr had gone to bring him back. On Wednesday evening last they were seen on their way home the negro walking handcuffed but with a stick in his hands behind Mr. Orr. This circumstance becoming known to Mr. O's overseer his suspicions were for the first aroused at his absence and on Saturday several persons were sent in search in the direction in which Mr. Orr and his negro were seen. The search was unsuccessful and yesterday morning it was resumed all the negros in the camp being sent out. The body was found within about a mile and a half of his camp. His head was broken in several places and his throat bearing the mark of his having been stabbed. It is supposed the negro struck him from behind and knocked him from his horse and afterwards inflicted the other wounds and then dragged the body into the woods about one hundred yards. The saddle on which Mr. Orr rode was also found but his horse, watch, and money were taken. The negro is still at large. Mr. Orr was a very extensive contractor and is described as having been a kind and generous master.

The same day the body was reported found, the Savannah Morning News reported "The slave supposed to have murdered his master, Mr. A. J. Orr, was arrested on Monday at Dillon's Bridge, by the keeper of the Toll Gate, John Hart, and Cornelius Connelly, who brought him to the city and lodged him in jail."[32]

The Liberator, abolitionist newspaper of Boston, briefly covered the incident on October 19, 1855.[33] In November 1855, D. W. Orr listed "FOR sale Cheap for Cash, or in exchange for Negroes, the Warehouse and Lot formerly occupied by A. J. Orr for the sale of Negroes."[34]

Orr v. Huff, 27 Ga. 422 (1859)

editShortly before A. J. Orr was killed, a Georgia planter named Travis Huff filed suit against him, seeking $1,000 in damages resulting from the purchase of a nine-year-old named Fanny.[28] The issue before the jury was whether A. J. Orr had knowingly sold Huff a "defective" slave, and whether or not her declining health and eventual death could have been foreseen by the slave dealer who sold Fanny to Huff. In addition to Fanny, according to the court record, Travis Huff later purchased a "negro woman and two children" from A. J. Orr in 1853 or 1854, and did not report an issue with Fanny to Orr until 1854 or 1855.[35][a]

Huff presented evidence from two doctors who had examined Fanny stating that she presented with "chorea, or St. Vitus dance," had epileptic seizures seven to eight times a day, microcephaly, was minimally verbal, "was scarcely able to stand," and had "idiotic expression of countenance" and was "almost entirely senseless."[28] Fanny apparently died at the Huff place in about March or April 1855, at approximately age 14.[28] According to the published case record, Huff's son William Huff testified, "...witness worked with her, and soon discovered that she was very dull, and afterwards that she was of unsound mind; she gradually grew worse as long as witness remained; left home in 1853; thought she was older than described in the bill of sale; never grew much after his father bought her; won't say she was a confirmed idiot when he left his father, but she was worthless; did not comprehend what was said to her; never considered her sound in mind after she was put to work, and had no sufficient opportunity of judging before."[37]

D. W. Orr testified that he was only the administrator of his brother's estate and thus had no personal stake in the outcome, and that he had purchased Fanny in Virginia for his brother to resell in Georgia about four months prior to her sale to Huff and "saw her frequently before the sale. Witness has bought and sold negroes, several hundred; hardly ever made a mistake in the soundness of one..."[35] Orr also testified that he offered a guarantee that he "...after he has examined and purchased a negro, and pronounced him or her sound, would release a seller from his warranty for five dollars; is perfectly satisfied that the girl, Fanny, was sound in mind and body, at the time she was sold to plaintiff."[35] On cross-examination he explained that "was sometimes a partner of A. J. Orr, in the purchase and sale of negroes, both before and after the sale of Fanny to plaintiff, but had no interest whatever in her; sometimes bought on his own account, and sometimes A. J. Orr bought on his account. Bought the girl Fanny, with the funds of A. J. Orr, and was not interested in her purchase; was not then in the trade."[38] The jury found for the plaintiff and awarded him the $400 he paid for Fanny, plus interest from the date of purchase.[38] Orr requested a new trial and appealed when it was denied; no new trial was granted.[39]

D. W. Orr, from 1856 to 1867

editRailroad contracts and railroad-shanty runaways

editIn June 1856, Orr advertised heavily for the recapture of two slaves, offering $100 for the return of the pair. His ad read, "Ran away from my Rail Road Shantees, (in Liberty county, Ga.,) on Sunday night, the 11th of May, two negro fellows, Jim and Jack Gill, both black and of medium size, Jim is 24 years old, and was raised by John Nivens, of York District, South Carolina. Jack Gill is about 30 years old, and was purchased by A. J. Orr, at Thomas Massey's sale, in Lancaster District, South Carolina, in December, 1854. I think they will try to make their way back to where they were raised...Address me at Winchester, Macon county, Georgia, or James Hennigan, Pineville, Mecklenburg county, N. C."[40][41]

In August 1856, there was another escape from Orr's Liberty County "railroad shantees." The fugitive was a 24-year-old black man of medium build named Ephraim who was "raised by Mr. Ship of Lincoln County, and sold to me by W. P. Bynum of said county, last February." Orr surmised that Ephraim was in Charlotte, North Carolina, or near "W. P. Bynum's in Lincoln county, or Wm. Ship's, of Gaston county, as he has relations at all those points."[42]

The Milledgeville Railroad annual report of 1862 stated, "The line between Sparta, and Macon was contracted to Messrs. Orr, Lockett, Thompson, Jossey, Collins, Phillips and Gilbert, Lane and Brown, Culver, Bowen, and some smaller contractors. The forces now engaged on the road number one thousand hands, working two hundred and ten carts."[43] The company asserted that the road would be completed by January 1, 1864.[44] The Orrs may have been compensated with railroad company stock as a line item in the financial reporting read "Deduct stock received in the hands of the Company as per contract with D. W. Orr and others $39,447.78."[45]

Family and business

editIn August 1856, Orr listed for sale 350 acres "on the public road," in Winchester, Georgia, two miles from the South-Western Railroad depot.[46] The land had "two hundred and fifty acres cleared and in cultivation, the balance wood land; will be sold cheap for cash or approved notes."[46]

According to a later account, following the deaths of the A. J. and Susan Orr, D. W. Orr "became at once the guardian and father of his brother's sons."[4] In September 1856, he listed for sale A. J. Orr's "two-story dwelling house and lot" in Macon.[47] He also organized an administrator's sale of his deceased brother's possessions, including "all the Household and Kitchen furniture, one new Piano, one good Two-Horse Carriage and Harness complete, [and] one Two-Horse Wagon and Harness."[48] At the same time he listed a wood lot, which had been owned jointly by the Orr brothers and Judge T. G. Halt.[49] Lastly, in October 1856, D. W. Orr applied to be administrator of the estate of Susan A. Orr, who had been his sister-in-law, and applied for guardianship of John W. Orr and Andrew J. Orr, the minor children of A. J. Orr and Susan A. Orr.[50] In 1858 Orr again served on a Bibb County grand jury.[51] He spent New Year's 1859 in Hannibal, Missouri.[52] In May 1860, D. W. Orr hosted the wedding of Mary Elizabeth Orr to Calvin Nixon.[53] At the time of the U.S. census in August 1860, Orr was living with his wife and his two nephews near Montezuma post office, Bibb County, Georgia, with each of the male Orrs declaring that they owned several thousand dollars of real and/or personal property.[54] Orr listed his occupation as railroad contractor.[54] In December 1860, Orr advertised his the sale of residence at Winchester, along with 10 "good broke miles" and "some stock hogs".[55]

American Civil War and Reconstruction

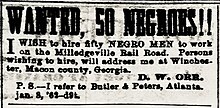

editIn 1862, Orr advertised in the Southern Confederacy newspaper of Atlanta, that he wished to hire 50 slaves to work on the Milledgeville Railroad, and gave as a reference Peters & Butler of Atlanta.[56] The editor of the paper elsewhere printed a blurb encouraging slave owners to work with Orr: "Hire Out the Negroes. We refer all who have negro men to hire, to the card of D. W. Orr, Esq. We know him personally, and he is a responsible man."[57] In January 1863 he was trying to sell his 800-acre plantation at Winchester, "possession given January next."[58] The next month he was again advertising for laborers to build a railroad: "30 Negro Men Wanted to work on Milledgeville Railroad in healthy country; the Negroes will be well treated, and payments made quarterly or half yearly."[59]

In October 1863, Orr donated $50 to Major Sparks' campaign "for the benefit of the sick and wounded soldiers."[60]

Three years later, in 1866, after the war was over, D. W. Orr advertised that he wanted to buy an oak and hickory plantation and rent two cotton plantations.[61] In 1867 he requested letters of dismission, marking an end to his administration of the estates of his brother and sister-in-law.[62]

D. W. Orr died near Griffin, Georgia in approximately October or November 1867.[4]

Legacy

editIn the early 20th century, scholar Frederic Bancroft traveled the U.S. South soliciting first-person accounts of the interstate slave trade. One such interview was conducted in Macon, Georgia, and published in Bancroft's 1931 landmark Slave-Trading in the Old South:[63]

A former mayor seemed to find a novel and pleasing sensation in looking into the distant past and describing conditions he was familiar with in his youth. "...A. J. and D. W. Orr also had a slave-trading place on Cotton Avenue. Charles F. Stubbs was another trader. These were the big dealers. There were still others...The largest dealers, such as Dean, Phillips, the Orrs and Stubbs, regularly went to Richmond and brought back slaves; Richmond was the headquarters. The barbarity of that traffic was unconscionable. I was born in Georgia and my father had slaves. For my brother, I once bought of the Orrs a negro girl named Charlotte and paid $575."[63]

Bancroft crossed paths with the Orrs again in Natchez, Mississippi in 1902, when he interviewed an American Civil War veteran named Pleasant Jones:[64]

Pleasant Jones was born in Buckingham county, Virginia. When about 18, his master, James Miller, sold him to a trader in Richmond named Orr, who brought him to Macon, Georgia, partly by water and partly by the cars. Orr was undoubtedly one of the firm so well remembered by the ex-Mayor and other old residents of Macon. Orr sold him to William Jarvis, who took him to New Orleans. "Jarvis got too drunk; Holmes bought me and later sol' me to Thomas Wadell, who lived in Texas. Wadell later brought me back to New O'leens and sol' me to James Gillespie." Jones was sold six times. During the Civil War he ran away to the Federal Army. This explained his comforts and his wearing part of the uniform of the Grand Army of the Republic.[64]

When A. J. Orr's son A. J. Orr died in 1920, his obituary stated that he was a beloved citizen of Macon, a devout Baptist, and "Like his father, he was true to all the traditions and causes of the south. He was a leading figure in upholding white supremacy during reconstruction days." [65]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ There is a WPA Slave Narrative from a woman who had been enslaved by Travis Huff when she was a child. Mary Huff told the interviewer that Mr. Huff kept approximately 12 slaves but only one of them was male; Huff "usually purchased women with children and there were no married couples living on his place."[36]

References

edit- ^ Flanders (1933), p. 187.

- ^ Tadman (1996), p. 21.

- ^ a b Source Citation: The National Archives in Washington, DC; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M432; Residence Date: 1850; Home in 1850: Macon, Bibb, Georgia; Roll: 61; Page: 155b, Line Number: 15, Dwelling Number: 64, Family Number: 66 Source Information: Ancestry.com. 1850 United States Federal Census[database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

- ^ a b c d e Macon Telegraph (1867).

- ^ "Public Meeting". The Weekly Telegraph. February 13, 1844. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ "New Goods at Winship's". Georgia Journal and Messenger. October 27, 1847. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ "New Dry Goods, Hat and Shoe Store". Georgia Journal and Messenger. December 14, 1843. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ "Fire at Columbus". The Weekly Telegraph. October 13, 1846. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ a b Tadman (1996), p. 26–27.

- ^ a b Pegues (1892), p. 521.

- ^ "City Arrivals". Richmond Times-Dispatch. February 24, 1847. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ "GOODS AT COST! Bargains in Dry Goods and Clothing". Georgia Journal and Messenger. June 16, 1847. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-07-12.

- ^ a b Tadman (1996), p. 27.

- ^ "$40 Dollars Reward". The Daily Constitutionalist and Republic. May 30, 1848. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ Source Citation The National Archives in Washington, DC; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M432; Residence Date: 1850; Home in 1850: Richmond, Richmond (Independent City), Virginia; Roll: 951; Page: 399a Source Information Ancestry.com. 1850 United States Federal Census[database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

- ^ a b "To Rent". The Weekly Telegraph. October 22, 1850. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ Bellamy (1984), p. 305.

- ^ Orr v. Huff (1859), p. 422.

- ^ Source Information Ancestry.com. 1850 U.S. Federal Census - Slave Schedules [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004. Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Seventh Census of the United States, 1850. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1850. M432, 1,009 rolls.

- ^ "100 Negroes for Sale". The Weekly Telegraph. October 1, 1850. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ "Removal". Georgia Journal and Messenger. September 3, 1851. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ "Grand Jury". Georgia Journal and Messenger. July 7, 1852. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ Justices of the Inferior Court v. Orr (1852), p. 140.

- ^ "Second Panel". Georgia Journal and Messenger. April 18, 1855. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ a b South-Western Railroad Company (1869), p. 210.

- ^ a b "Committed". Richmond Dispatch. April 27, 1853. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ a b "Sent on". Richmond Dispatch. April 28, 1853. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ a b c d Orr v. Huff (1859), p. 423.

- ^ "Murder of a Railroad Contractor". The Baltimore Sun. August 3, 1855. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ "We regret to learn that Mr. A. J. Orr..." The North Carolina Whig. August 14, 1855. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ "The body of A. J. Orr". The Charleston Daily Courier. August 1, 1855. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ Annals of Savannah (1938), p. 111.

- ^ "Brutal Murder". The Liberator. October 19, 1855. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ "City Property for Sale". The Weekly Telegraph. November 13, 1855. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ a b c Orr v. Huff (1859), p. 425.

- ^ Mary Huff interview (1941), p. 237.

- ^ Orr v. Huff (1859), p. 424.

- ^ a b Orr v. Huff (1859), p. 426.

- ^ Orr v. Huff (1859), p. 426–427.

- ^ "$100 Reward". The Charlotte Democrat. June 3, 1856. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "$100.00 Reward!". Lexington and Yadkin Flag. June 20, 1856. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Ranaway". The Charlotte Democrat. November 25, 1856. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ Milledgeville Railroad Company (1862), p. 9.

- ^ Milledgeville Railroad Company (1862), p. 10.

- ^ Milledgeville Railroad Company (1862), p. 14.

- ^ a b "Plantation for Sale in Macon Co". Georgia Journal and Messenger. August 20, 1856. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Dwelling House and Lot". The Weekly Telegraph. September 16, 1856. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Administrator's Sale". The Weekly Telegraph. September 23, 1856. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Wood Lot for Sale Near Macon". Georgia Journal and Messenger. September 24, 1856. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Dickerson W. Orr". Georgia Journal and Messenger. October 8, 1856. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Presentments of the Grand Jury". The Weekly Telegraph. April 20, 1858. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Hotel Arrivals - Planters' House". Hannibal Daily Messenger. January 1, 1859. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Married". The Weekly Telegraph. May 18, 1860. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ a b Source Citation The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653; Residence Date: 1860; Home in 1860: Georgia Militia District 770, Macon, Georgia; Roll: M653_130; Page: 124; Family History Library Film: 803130 Source Information Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census[database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

- ^ "NOTICE - Residence for Sale". The Weekly Telegraph. December 13, 1860. p. 8. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "WANTED, 50 NEGROES". Southern Confederacy. January 9, 1862. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Hire Out the Negroes". Southern Confederacy. January 8, 1862. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Desirable Plantation and Residence in South-Western Georgia". The Macon Telegraph. February 5, 1863. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "30 Negro Men Wanted". The Macon Telegraph. February 18, 1863. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "...list of contributors, in money, for the benefit of the sick and wounded soldiers..." The Macon Telegraph. October 1, 1863. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Cotton Plantations". The Macon Telegraph. October 19, 1866. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Georgia, Bibb County". The Weekly Telegraph. August 2, 1867. p. 7. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ a b Bancroft (2023), pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b Bancroft (2023), pp. 307.

- ^ Atlanta Journal (1920).

Books and articles

edit- Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. Slave Trading in the Old South (Original publisher: J. H. Fürst Co., Baltimore). Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- Bellamy, Donnie D. (1984). "Macon, Georgia, 1823–1860: A Study in Urban Slavery". Phylon. 45 (4). Clark Atlanta University: 298–310. doi:10.2307/274910. ISSN 0031-8906. JSTOR 274910. OCLC 49976270.

- Flanders, Ralph Betts (1933). "Chapter VIII. The Acquisition and Hire of Slaves". Plantation Slavery in Georgia. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. LCCN 33037653. OCLC 9876467.

- Pegues, Rev. Albert Witherspoon (1892). "Rev. Ralph R. Watson". Our Baptist Ministers and Schools. Springfield, Massachusetts: Willey & Company. pp. 520–523 – via Google Books.

- Tadman, Michael (1996). "The Hidden History of Slave Trading in Antebellum South Carolina: John Springs III and Other 'Gentlemen Dealing in Slaves'". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. 97 (1): 6–29. JSTOR 27570133.

- WPA (1938). Annals of Savannah, 1850–1937: A Digest and Index of the Newspaper Record of Events and Opinions in Eighty-Seven Volumes, Abstracted from the Files of the Savannah Morning News. Vol. 7 (1855). Project Number 4256, Works Progress Administration of Georgia, Area Eight, Savannah. Savannah Public Library – via UMI, HathiTrust.

Primary sources

edit- n.a. (November 29, 1867). Sneed, J. R.; Boykin, S. (eds.). "In Memoriam". Weekly Georgia Telegraph. Vol. II, no. 53. Macon, Georgia. p. 8.

- n.a. (November 1, 1920). "Mr. A. J. Orr, Beloved Macon Citizen, Is Dead". The Atlanta Journal. Vol. XXXVIII, no. 250. Atlanta, Georgia. p. 9.

- Federal Writers' Project (1941). "Informant: Mary Huff, 561 Cotton Avenue, Macon, Georgia". Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Vol. IV (Georgia Narratives), Part 2, Garey–Jones. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 233–237.

- Georgia Supreme Court; Cobb, Thos. R. R. (1853). The Justices of the Inferior Court of Bibb County, plaintiffs in error, vs. A. J. & D. W. Orr, defendants in error in Reports of Cases in Law and Equity, Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Georgia, Containing the Decisions from Decatur, August Term, to Columbus, January Term, 1853, Inclusive. Vol. XII. Athens, Georgia: Christy & Kelsea. pp. 137–141 – via HathiTrust. — Reported as Justices of the Inferior Court v. Orr, 12 Ga. 137 (1852).

- Georgia Supreme Court; Martin, B. Y. (1860). Dickinson W. Orr, administrator, plaintiff in error, vs. Travis Huff, defendant in error in Reports of Cases in Law and Equity, Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Georgia, Containing the Decisions at Macon, January Term, 1859; and Part of the Decisions at Atlanta, March Term, 1859. Vol. XXVII. Columbus, Georgia: Columbus Times Steam Power Press. pp. 422–427 – via HathiTrust. — Reported as Orr v. Huff, 27 Ga. 422 (1859).

- Milledgeville Railroad Company (October 6, 1862). Report of the President, Directors, &c., of the Milledgeville R. Road Co., to the Stockholders (Report). Augusta, Georgia: Constitutionalist Print. – via Documenting the American South (docsouth.unc.edu).

- South-Western Railroad Company (1869). Report of the chief engineers, presidents, and superintendents of the South-western R.R. Co. of Georgia from no. 1 to 22, inclusive with the charter and amendments thereto (Report). Macon, Georgia: J. W. Burke & Co. – via Digital Library of Georgia (dlg.galileo.usg.edu).

Further reading

edit- "Entry for D W Orr, 13 August 1867". Georgia, Reconstruction Registration Oath Books, 1867–1868. FamilySearch.

- Granade, James A. (1993). "The Twilight of Cotton Culture: Life on a Wilkes County Plantation, 1924–1929". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 77 (2): 264–285. ISSN 0016-8297. JSTOR 40582709.