| This page is currently inactive and is retained for historical reference. Either the page is no longer relevant or consensus on its purpose has become unclear. To revive discussion, seek broader input via a forum such as the village pump. |

| Featured Article Archives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 Archive | 2006 Archive | 2007 Archive | 2008 Archive | 2011 Archive | 2012 Archive |

| Portal:France/Featured article/Layout | |||||

- August 2005

- September 2005

Brittany (French: Bretagne, Breton: Breizh; Gallo: Bertaèyn) is a former independent duchy, later a province of France. It is also, more generally, the name of the cultural area whose limits correspond to the old province.

The historical province of Brittany was split between two modern-day regions of France. 80% of Brittany has become the region of Brittany, while the remaining 20% of Brittany (Loire-Atlantique département with its préfecture Nantes, the old capital of the duchy of Brittany) has been grouped with other historical provinces (Anjou, Maine, and so on) to create the région of Pays-de-la-Loire (that is, "lands of the Loire"). For the reasons behind the splitting-up of Brittany, and the current debate around a reunification, see the Brittany article.

Brittany occupies a large peninsula in the northwest of France, lying between the English Channel to the north and the Bay of Biscay to the south. Its land area is 34,034 km² (13,137 sq. mi), which is about the same size as Taiwan, about 60% larger than Wales, and about 70% larger than Massachusetts.

In 2004 the population of Brittany is estimated at 4,200,000 inhabitants. 72% of these live in the Brittany region, while 28% of these live in the Pays-de-la-Loire region. At the 1999 census, the largest metropolitan areas were Nantes (711,120 inhabitants), Rennes (521,188 inhabitants), and Brest (303,484 inhabitants). Read more...

- October 2005

Generals Lecomte and Thomas being shot in Montmartre after their troops join the rebellion: a photographic reconstruction, not an actual photograph The Communards’ Wall (F.: Mur des Fédérés) at the Père Lachaise cemetery is where, on May 28, 1871, one-hundred forty-seven fédérés, combatants of the Paris Commune, were shot and thrown in an open trench at the foot of the wall. To the French left, especially socialists and communists, the wall became the symbol of the people’s struggle for their liberty and ideals. Many leaders of the French Communist Party, especially those involved in the French resistance, are buried nearby.

During the spring of 1871 the last of the combatants of the Commune entrenched themselves in the cemetery. The Armée versaillaise, which was summoned to suppress the Commune, had control over the area towards the end of the afternoon of May 28, and shot all of the prisoners against the wall.

The massacre of the Communards did not put an end to the repression. During the fighting between 20,000 and 35,000 deaths, and more than 43,000 prisoners were taken; afterwards, a military court pronounced about a hundred death sentences, more than 13,000 prison sentences, and close to 4,000 deportations to New Caledonia. Read more...

- November 2005

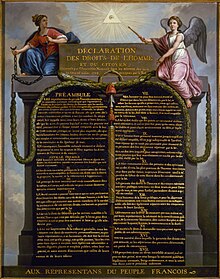

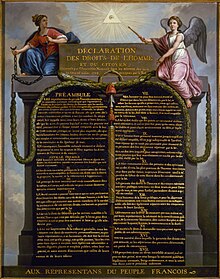

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: La Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen) is one of the fundamental documents of the French Revolution, defining a set of individual rights and collective rights of the people. It was adopted August 26, 1789, by the National Constituent Assembly (Assemblée nationale constituante), as the first step toward writing a constitution. It sets forth fundamental rights not only of French citizens but acknowledges these rights to all men without exception:

- "First Article – Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can be founded only on the common utility."

The principles set forth in the declaration are of constitutional value in present-day French law and may be used to oppose legislation or other government activities. Read more...

- December 2005

Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (French Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon) is a French overseas collectivity consisting of several small islands off the eastern coast of Canada near Newfoundland. It is the only remainder of the former colonial territory of New France.

Named the 'Eleven Thousand Virgins' by Portuguese explorer João Álvares Fagundes in 1521, the islands were also named the 'Islands of Saint-Pierre' by the French. During the 16th century, the islands were used as a base for the seasonal cod fishery by the French of La Rochelle, Granville, Saint-Malo and the Basque Country. Saint-Pierre was settled by the French in the early 17th century, abandoned under the Treaty of Utrecht, and returned to France in 1763 at the end of the Seven Years War. Between 1763 and 1778, the islands became a place of refuge for Acadian deportees from Nova Scotia. In 1778 the islands were attacked and the population deported by the British as retaliation for French support of the American Revolutionary War.

Although France regained the islands in 1783, by 1793, British hostility to the French Revolution and the fact that France had declared war with Britain led to another British attack on the islands and the deportation of the entire population. Read more...