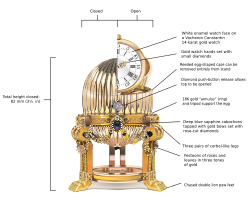

The Third Imperial egg is an Easter Fabergé egg created in the workshop of Peter Carl Fabergé for the Russian tsar Alexander III and presented to his wife, Maria Feodorovna, on Orthodox Easter of 1887. The egg was created in Louis XVI style and it consists of a solid 18K gold reeded case resting on a gold "annulus" (ring) with waveform decorations held up by three sets of corbel-like legs which end in lion's paws. Joining these legs are festoons of roses and leaves made in a variety of colored gold alloys and joined in the middle of each side by matching oval cabochon sapphires. Above each sapphire is a gold bow decorated with a series of tiny diamonds, and the front of the egg has a single much-larger diamond in an old-mine diamond clasp which when pressed releases the egg's lid to reveal its surprise.[1] The egg was lost for many years, but was rediscovered in 2012.[2] The rediscovery of this egg was announced publicly and covered in many news stories in 2014.

| Third Imperial Fabergé egg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Year delivered | 1887 |

| Customer | Alexander III |

| Recipient | Maria Feodorovna |

| Current owner | |

| Individual or institution | Unidentified private collector |

| Year of acquisition | 2014 |

| Design and materials | |

| Workmaster | August Holmström |

| Materials used | Jewels, gold, white enamel, diamond |

| Height | 82 millimetres (3.2 in) |

| Surprise | Vacheron & Constantin Lady's watch |

Surprise

edit14K gold Vacheron Constantin Lady's watch, with white enamel dial and openwork diamond set gold hands.

Exhibitions

edit- March 1902, Von Dervais Mansion Exhibition, St. Petersburg

- 14–17 April 2014, exhibited at Wartski, 14 Grafton Street, London

- 20 November 2021 – 8 May 2022, "Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution", Victoria and Albert Museum, London[3]

Provenance

edit| Custody dates | Custodian | Description at time of custody | Method of transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1886 to 1887 | Workshop of August Holmström, chief jeweller at House of Fabergé | Sale by maker (2160 roubles) | |

| April 1887 to September 1917 | Russian Imperial Cabinet, Empress Maria Feodorovna (later Dowager Empress), Anichkov Palace | "1887 -Easter Egg with clock, decorated with diamonds, sapphires and rose cut diamonds 2160 r(oubles)" (Account books of N. Petrov (Assistant Manager to the Imperial Cabinet)) | Confiscation |

| September 1917 to 17 February-24 March 1922 | Moscow Kremlin Armoury | "Art. 1548. 'A lady's gold watch, opened and set into a gold egg with one diamond. The latter on a gold tripod pedestal with three sapphires.' Number 1644" (reported Kremlin archive documentation) | Transfer |

| 17 February-24 March 1922 to Unknown | Special plenipotentiary of the Council of People's Commissars, Ivan Gavrilovich Chinariov | "One gold egg with watch, diamond push-piece and pedestal with 3 sapphires and rose cut diamonds" (description of Article 68/1548 in the records of the transfer to the Special plenipotentiary) | Unknown |

| Unknown to 7 March 1964 | "Clark" | "Gold Watch in egg- form case on wrought three- tone gold stand set with jewels, fourteen Karat gold watch in reeded egg shaped case with seventy-five point old mine clasp by Vacheron Constantin; on eighteen karat three-tone gold stand exquisitely wrought with an annulus, bordered with wave scrollings and pairs of corbel like legs cisele with a capping of roses, pendants of tint leaves depending to animalistic feet with ring stretcher: the annulus bears three medallions of cabochon sapphires surmounted by tiny bowknotted ribbons set with minute diamonds, which support very finely cisele three-tone gold swags of roses and leaves which continue downward and over the pairs of legs. Height 31/4 inches" (Parke Bernet Catalogue, 1964). | Sale by auction, Parke Bernet, New York ($2,450 USD) |

| Unknown | |||

| Unknown - About 2004[2] | A dealer in the American Midwest | Estimated $15,000 in gold and gem content | Sale at a "bric-a-brac market in the American Midwest" (for $13,302 USD) |

| About 2004[2] - About 2014[2] | A scrap dealer in the American Midwest | "The Lost Third Imperial Easter Egg by Carl Fabergé. Given by Alexander III Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias to Empress Marie Feodorovna for Easter 1887. The jewelled and ridged yellow gold Egg stands on its original tripod pedestal, which has chased lion paw feet and is encircled by coloured gold garlands suspended from cabochon blue sapphires topped with rose diamond set bows. It contains a surprise of a lady’s watch by Vacheron Constantin, with a white enamel dial and openwork diamond set gold hands. The watch has been taken from its case to be mounted in the Egg and is hinged, allowing it to stand upright. Made in the workshop of Fabergé’s Chief-Jeweller: August Holmström, St. Petersburg, 1886-1887. Height 8.2 cm".[4] | Sale to a private collector via Wartski (for an undisclosed amount) |

| 2014[2]- | Private Collection |

Finding the egg

editThe 1887 Imperial Easter egg was described by Russian Imperial Cabinet documents as:

"Easter egg with clock, decorated with diamonds, sapphires and rose-cut diamonds - 2160 r:"

"Gold egg with clock with diamond pushpiece on gold pedestal with 3 sapphires and rose-cut diamond roses"

"Gold egg with clock on diamond stand (?) on gold pedestal with 3 sapphires and rose-cut diamonds"

The Russian word for "clock" and "watch" is the same.

In March 1902, an egg identical to the egg recovered in 2012 was photographed in situ with other treasures of the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna in the Von Dervais Mansion Exhibition in St. Petersburg. The exhibition was titled Fabergé artifacts, antique miniatures and snuffboxes[5] which suggests the objects which are not miniatures or snuffboxes are from Fabergé.[6] The photograph from this exhibit survives and the egg identified in 2011 as the Third Imperial Egg is seen sitting in a vitrine in which the other eleven visible eggs are all identifiable as Fabergé eggs belonging to Maria Feodorovna (Palmade and Palmade 2011).

The Russian Imperial Cabinet descriptions fit a description in the 1922 Soviet inventory of confiscated items of an egg with sapphires, a diamond pushpiece and a gold pedestal.[6] The 1922 inventory does not specify that this egg is by Fabergé, but it is the egg description in that inventory which is most consistent with the Fabergé one in the earlier account books of the Russian Imperial Cabinet.[5] The failure to identify the egg as Fabergé during the 1917 to 1922 confiscation and transfers probably represents the beginning of its loss.

From the beginning of serious Fabergé scholarship until 2008, the Blue Serpent Clock Egg was identified as the 1887 Imperial Easter egg, although it had no sapphires, the elaborate style was more consistent with later Fabergé eggs, and the 1887 price of 2160 rubles seemed too low.[7] Therefore, a theory of a lost Third Imperial Egg was not put forth until November 2008 when Annemiek Wintraecken, a Fabergé egg researcher/popularizer on her website, postulated that the Blue Serpent Clock Egg was in fact the supposedly missing 1895 egg, leaving the 1887 egg unaccounted for.[8]

On 6 July 2011, two Fabergé researchers in the US, Vincent and Anna Palmade[4] discovered an image of an egg identical to the one in the 1902 Von Dervais exhibition photograph in an old catalog for a March 1964 auction at Parke-Bernet (now Sotheby's).[9] The "newly discovered image of the egg ... prompted a frantic search by Sotheby's to trace its whereabouts" and presumably led to the article by Roya Nikkhah titled "Is this £20 million nest-egg on your mantelpiece?" published on 13 August 2011 in The Telegraph.

The 2011 Telegraph article included an interview with Kieran McCarthy, "a Fabergé expert from the Mayfair jeweller Wartski" and McCarthy stated "whoever has this piece will have no idea of its provenance and significance – nor will they know they are sitting on a royal relic which could be worth £20 million." McCarthy hypothesized that there "is every chance this egg is somewhere in this country, because even though it was not sold as Fabergé in the 1964 auction, a lot of Fabergé collectors and buyers of 'Fabergé-style' works of art were English collectors at the time." While the hypothesis of current English ownership proved invalid, the search efforts and commentary in the United Kingdom led to the publication of the Telegraph article which included the black and white photograph from the 1964 catalog and repeated much of the description, including that the egg contained "a gold watch by the Swiss watch maker Vacheron & Constantin." The article was archived online and thereafter available to the global (English-reading) audience and searchable on Google.

In 2012 a scrap dealer in the United States went online to research the gold egg which had "languished in his kitchen for years." He had purchased the egg about a decade before for $13,302 "based on its weight and estimated value of the diamonds and sapphires featured in the decoration" intending "to sell it on to a buyer who would melt it down" but "prospective buyers thought he had over-estimated the price and turned him down".[2] The scrap dealer "Googled 'egg' and 'Vacheron Constantin', a name etched on the timepiece inside"[2] and the result was the 2011 Telegraph article. He "recognised his egg in the picture".[2]

The scrap dealer contacted Kieran McCarthy and flew to London to get an opinion from Wartski. McCarthy reported the scrap dealer "hadn't slept for days" and "brought pictures of the egg and I knew instantaneously that was it. I was flabbergasted – it was like being Indiana Jones and finding the Lost Ark".[2] McCarthy subsequently flew to the US to verify the discovery and described the find location as "a very modest home in the Mid West, next to a highway and a Dunkin' Donuts. There was the egg, next to some cupcakes on the kitchen counter".[2] A picture of the egg in situ on the kitchen counter next to a cupcake was subsequently included in the follow-up Telegraph article in March 2014 and was in circulation in various articles on the Internet.

McCarthy confirmed to the scrap dealer that he had an Imperial Fabergé Easter Egg and the dealer "etched Mr. McCarthy's name and the date into the wooden bar stool on which Mr. McCarthy sat to examine the egg".[2] McCarthy noted that the scrap dealer "invested some money in this piece and hung on to it because he was too stubborn to sell it for a loss" and "I have been around the most marvellous discoveries in the art world, but I don't think I've ever seen one quite like this – finding this extraordinary treasure in the middle of nowhere".[2]

Wartski bought the egg on behalf of a Fabergé collector who allowed the firm to exhibit the piece, for the first time in 112 years, in April 2014. As evidence of its journey, the egg "has several scratches on it where the metal was tested for its gold content by prospective buyers ... the new buyer thought they enhanced the piece because they are part of its history".[2]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Christel McCanless (2017). "Fabergé Imperial Egg Chronology". Fabergé Research Site. Archived from the original on 2017-08-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Singh, Anita (18 Mar 2014). "The £20m Fabergé egg that was almost sold for scrap". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ V&A - Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution

- ^ a b McCarthy, Kieran. "The Lost Third Imperial Easter Egg by Carl Fabergé". www.wartski.com. Wartski. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ a b Proler, Lynette G.; Skurlow, Valentin; Fabergé, Tatiana; Skurlow, Valentin V. (1997). The Fabergé imperial Easter eggs (Reprinted with corr. ed.). London: Christie, Manson and Woods Ltd. p. Check. ISBN 9780903432481.

- ^ a b "Mieks Fabergé Eggs". www.wintraecken.nl.

- ^ Lopato, Marina; von Habsburg, Géza (1993). Fabergé : imperial jeweller. St. Petersburg, Russia: State Hermitage Museum. p. Check. ISBN 9780883971109.

- ^ Annemiek Wintraecken, The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs: New Discoveries Revise Timeline, Fabergé Research Newsletter (November 2008)

- ^ Nikkhah, Roya. "Is this £20 million nest-egg on your mantelpiece?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

External links

edit