Solanine is a glycoalkaloid poison found in species of the nightshade family within the genus Solanum, such as the potato (Solanum tuberosum), the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and the eggplant (Solanum melongena). It can occur naturally in any part of the plant, including the leaves, fruit, and tubers. Solanine has pesticidal properties, and it is one of the plant's natural defenses. Solanine was first isolated in 1820 from the berries of the European black nightshade (Solanum nigrum), after which it was named.[1] It belongs to the chemical family of saponins.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

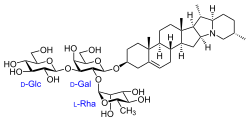

| IUPAC name

Solanid-5-en-3β-yl α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-[β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)]-β-D-galactopyranoside

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2S,3R,4R,5R,6S)-2-{[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-5-Hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-2-{[(2S,4aR,4bS,6aS,6bR,7S,7aR,10S,12aS,13aS,13bS)-4a,6a,7,10-tetramethyl-2,3,4,4a,4b,5,6,6a,6b,7,7a,8,9,10,11,12a,13,13a,13b,14-icosahydro-1H-naphtho[2′,1′:4,5]indeno[1,2-b]indolizin-2-yl]oxy}-4-{[(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy}oxan-3-yl]oxy}-6-methyloxane-3,4,5-triol | |

| Other names

α-Solanine; Solanin; Solatunine

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.039.875 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C45H73NO15 | |

| Molar mass | 868.06 |

| Appearance | white crystalline solid |

| Melting point | 271 to 273 °C (520 to 523 °F; 544 to 546 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Solanine poisoning

editSymptoms

editSolanine poisoning is primarily displayed by gastrointestinal and neurological disorders. Symptoms include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, stomach cramps, burning of the throat, cardiac dysrhythmia, nightmares, headache, dizziness, itching, eczema, thyroid problems, and inflammation and pain in the joints. In more severe cases, hallucinations, loss of sensation, paralysis, fever, jaundice, dilated pupils, hypothermia, and death have been reported.[2][3][4]

Ingestion of solanine in moderate amounts can cause death. One study suggests that doses of 2 to 5 mg/kg of body weight can cause toxic symptoms, and doses of 3 to 6 mg/kg of body weight can be fatal.[5]

Symptoms usually occur 8 to 12 hours after ingestion, but may occur as rapidly as 10 minutes after eating high-solanine foods.[citation needed]

Correlation with birth defects

editSome studies show a correlation between the consumption of potatoes suffering from late blight (which increases solanine and other glycoalkaloid levels) and the incidence of spina bifida in humans.[citation needed] However, other studies have shown no correlation between potato consumption and the incidence of birth defects.[6]

Livestock poisoning

editLivestock can also be susceptible to glycoalkaloids. High concentrations of solanine are necessary to cause death to mammals. The gastrointestinal tract cannot efficiently absorb solanine, which helps decrease its strength to the mammal body.[7] Livestock can hydrolyze solanine and excrete its contents to diminish its presence in the body.[7]

Mechanism of action

editThere are several proposed mechanisms of how solanine causes toxicity in humans, but the true mechanism of action is not well understood. Solanum glycoalkaloids have been shown to inhibit cholinesterase, disrupt cell membranes, and cause birth defects.[8] One study suggests that the toxic mechanism of solanine is caused by the chemical's interaction with mitochondrial membranes. Experiments show that solanine exposure opens the potassium channels of mitochondria, increasing their membrane potential. This, in turn, leads to Ca2+ being transported from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm, and this increased concentration of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm triggers cell damage and apoptosis.[9] Potato, tomato, and eggplant glycoalkaloids like solanine have also been shown to affect active transport of sodium across cell membranes.[10] This cell membrane disruption is likely the cause of many of the symptoms of solanine toxicity, including burning sensations in the mouth, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, internal hemorrhaging, and stomach lesions.[11]

Biosynthesis

editSolanine is a glycoalkaloid poison created by various plants in the genus Solanum, such as the potato plant. When the plant's stem, tubers, or leaves are exposed to sunlight, it stimulates the biosynthesis of solanine and other glycoalkaloids as a defense mechanism so it is not eaten.[12] It is therefore considered to be a natural pesticide.[citation needed]

Though the structures of the intermediates in this biosynthetic pathway are shown, many of the specific enzymes involved in these chemical processes are not known. However, it is known that in the biosynthesis of solanine, cholesterol is first converted into the steroidal alkaloid solanidine. This is accomplished through a series of hydroxylation, transamination, oxidation, cyclization, dehydration, and reduction reactions.[13]Specifically, solanidine formation involves sequential hydroxylation, transamination, and cyclization reactions[1].The solanidine is then converted into solanine through a series of glycosylation reactions catalyzed by specific glycosyltransferases.[12]

Plants like the potato and tomato constantly synthesize low levels of glycoalkaloids like solanine. However, under stress, such as the presence of a pest or herbivore, they increase the synthesis of compounds like solanine as a natural chemical defense.[14] This rapid increase in glycoalkaloid concentration gives the potatoes a bitter taste, and stressful stimuli like light also stimulate photosynthesis and the accumulation of chlorophyll. As a result, the potatoes turn green, and are thus unattractive to pests.[15] Other stressors that can stimulate increased solanine biosynthesis include mechanical damage, improper storage conditions, improper food processing, and sprouting.[16] The largest concentration of solanine in response to stress is on the surface in the peel, making it an even better defense mechanism against pests trying to consume it.[17]

Safety

editSuggested limits on consumption of solanine

editToxicity typically occurs when people ingest potatoes containing high levels of solanine. The average consumption of potatoes in the U.S. is estimated to be about 167 g of potatoes per day per person.[11] There is variation in glycoalkaloid levels in different types of potatoes, but potato farmers aim to keep solanine levels below 0.2 mg/g.[18] Signs of solanine poisoning have been linked to eating potatoes with solanine concentrations of between 0.1 and 0.4 mg per gram of potato.[18] The average potato has 0.075 mg solanine/g potato, which is equal to about 0.18 mg/kg based on average daily potato consumption.[19]

Calculations have shown that 2 to 5 mg/kg of body weight is the likely toxic dose of glycoalkaloids like solanine in humans, with 3 to 6 mg/kg constituting the fatal dose.[20] Other studies have shown that symptoms of toxicity were observed with consumption of even 1 mg/kg.[11]

Storage of potatoes

editVarious storage conditions can have an impact on the level of solanine in potatoes. Glycoalkaloid levels increase when potatoes are exposed to light because light increases synthesis of glycoalkaloids like solanine.[18] Potatoes stored in a dark place avoid increased solanine synthesis. Potatoes that have turned green due to increased chlorophyll and photosynthesis are indicative of increased light exposure and are therefore associated with high levels of solanine.[20] Synthesis of solanine is also stimulated by mechanical injury because glycoalkaloids are synthesized at cut surfaces of potatoes.[18] Storage of potatoes for extended periods of time has also been associated with increased solanine content.[21] A study found that the solanine levels in Kurfi Jyoti and Kurfi Giriraj potatoes increase solanine levels by 0.232 mg/g and 0.252 mg/g respectively after being poorly stored in a heap.[22]

Effects of cooking on solanine levels

editMost home processing methods like boiling, cooking, and frying potatoes have been shown to have minimal effects on solanine levels. For example, boiling potatoes reduces the α-chaconine and α-solanine levels by only 3.5% and 1.2% respectively, but microwaving potatoes reduces the alkaloid content by 15%.[23] Deep frying at 150 °C (302 °F) also does not result in any measurable change. Alkaloids like solanine have been shown to start decomposing and degrading at approximately 170 °C (338 °F), and deep-frying potatoes at 210 °C (410 °F) for 10 minutes causes a loss of ~40% of the solanine.[10] Freeze-drying and dehydrating potatoes has a very minimal effect on solanine content.[24][25]

The majority (30–80%) of the solanine in potatoes is found in the outer layer of the potato.[25] Therefore, peeling potatoes before cooking them reduces the glycoalkaloid intake from potato consumption. Fried potato peels have been shown to have 1.4–1.5 mg solanine/g, which is seven times the recommended upper safety limit of 0.2 mg/g.[18] Chewing a small piece of the raw potato peel before cooking can help determine the level of solanine contained in the potato; bitterness indicates high glycoalkaloid content.[18] If the potato has more than 0.2 mg/g of solanine, an immediate burning sensation will develop in the mouth.[18]

Recorded human poisonings

editThough fatalities from solanine poisoning are rare, there have been several notable cases of human solanine poisonings. Between 1865 and 1983, there were around 2000 documented human cases of solanine poisoning, with most recovering fully and 30 deaths.[26] Because the symptoms are similar to those of food poisoning, it is possible that there are many undiagnosed cases of solanine toxicity.[27]

In 1899, 56 German soldiers fell ill due to solanine poisoning after consuming cooked potatoes containing 0.24 mg of solanine per gram of potato.[28] There were no fatalities, but a few soldiers were left partially paralyzed and jaundiced. In 1918, there were 41 cases of solanine poisoning in people who had eaten a bad crop of potatoes with 0.43 mg solanine/g potato with no recorded fatalities.[25]

In Scotland in 1918, there were 61 cases of solanine poisoning after consumption of potatoes containing 0.41 mg of solanine per gram of potato, resulting in the death of a five-year old.[29]

A case report from 1925 reported that 7 family members who ate green potatoes fell ill from solanine poisoning two days later, resulting in the deaths of the 45-year-old mother and 16-year-old daughter. The other family members recovered fully.[19] In another case report from 1959, four members of a British family exhibited symptoms of solanine poisoning after eating jacket potatoes containing 0.5 mg of solanine per gram of potato.[citation needed]

There was a mass solanine poisoning incident in 1979 in the U.K., when 78 adolescent boys at a boarding school exhibited symptoms after eating potatoes that had been stored improperly over the summer.[30] Seventeen of them ended up hospitalized, but they all recovered. The potatoes were determined to have between 0.25 and 0.3 mg of solanine per gram of potato.[citation needed]

Another mass poisoning was reported in Canada in 1984, after 61 schoolchildren and teachers showed symptoms of solanine toxicity after consuming baked potatoes with 0.5 mg of solanine per gram of potato.[31]

In potatoes

editPotatoes naturally produce solanine and chaconine, a related glycoalkaloid, as a defense mechanism against insects, disease, and herbivores. Potato leaves, stems, and shoots are naturally high in glycoalkaloids.[citation needed]

When potato tubers are exposed to light, they turn green and increase glycoalkaloid production. This is a natural defense to help prevent the uncovered tuber from being eaten. The green colour is from chlorophyll, and is itself harmless. However, it is an indication that increased level of solanine and chaconine may be present. In potato tubers, 30–80% of the solanine develops in and close to the skin, and some potato varieties have high levels of solanine.[citation needed]

Some potato diseases, such as late blight, can dramatically increase the levels of glycoalkaloids present in potatoes. Tubers damaged in harvesting and/or transport also produce increased levels of glycoalkaloids; this is believed to be a natural reaction of the plant in response to disease and damage.[citation needed]

Also, the tuber glycoalkaloids (such as solanine) can be affected by some chemical fertilization. For example, different studies have reported that glycoalkaloids content increases by increasing the concentration of nitrogen fertilizer.[32][33]

Green colouring under the skin strongly suggests solanine build-up in potatoes, although each process can occur without the other. A bitter taste in a potato is another – potentially more reliable – indicator of toxicity. Because of the bitter taste and appearance of such potatoes, solanine poisoning is rare outside conditions of food shortage. The symptoms are mainly vomiting and diarrhea, and the condition may be misdiagnosed as gastroenteritis. Most potato poisoning victims recover fully, although fatalities are known, especially when victims are undernourished or do not receive suitable treatment.[34]

The United States National Institutes of Health's information on solanine strongly advises against eating potatoes that are green below the skin.[3]

In other plants

editFatalities are also known from solanine poisoning from other plants in the nightshade family, such as the berries of Solanum dulcamara (woody nightshade).[35]

In tomatoes

editSome, such as the California Poison Control Center, have claimed that unripe tomatoes and tomato leaves contain solanine. However, Mendel Friedman of the United States Department of Agriculture contradicts this claim, stating that tomatine, a relatively benign alkaloid, is the tomato alkaloid while solanine is found in potatoes. Food science writer Harold McGee has found scant evidence for tomato toxicity in the medical and veterinary literature.[36]

In popular culture

editDorothy L. Sayers's short story "The Leopard Lady", in the 1939 collection In the Teeth of the Evidence, features a child poisoned by potato berries injected with solanine to increase their toxicity.[citation needed]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Desfosses (1820). "Extrait d'une lettre de M. Desfosses, pharmacien, à Besançon, à M. Robiquet" [Extract of a letter from Mr. Desfosses, pharmacist in Besançon, to Mr. Robiquet]. Journal de Pharmacie. 2nd series (in French). 6: 374–376.

- ^ "Solanine poisoning – how does it happen?". 7 February 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Potato plant poisoning – green tubers and sprouts

- ^ K. Annabelle Smith (21 October 2013). "Horrific Tales of Potatoes That Caused Mass Sickness and Even Death". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Executive Summary of Chaconine & Solanine Archived 15 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Solanine and Chaconine". Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ a b Dalvi RR, Bowie WC (February 1983). "Toxicology of solanine: an overview". Vet Hum Toxicol. 25 (1): 13–5. PMID 6338654.

- ^ Friedman M, McDonald GM (1999). "Postharvest Changes in Glycoalkaloid Content of Potatoes". In Jackson LS, Knize MG, Morgan JN (eds.). Impact of Processing on Food Safety. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 459. pp. 121–43. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4853-9_9. ISBN 978-1-4615-4853-9. PMID 10335373.

- ^ Gao SY, Wang QJ, Ji YB (2006). "Effect of solanine on the membrane potential of mitochondria in HepG2 cells and [Ca2+]i in the cells". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (21): 3359–67. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i21.3359. PMC 4087866. PMID 16733852.

- ^ a b Friedman M (November 2006). "Potato Glycoalkaloids and Metabolites Roles in the Plant and in the Diet". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (23): 8655–8681. doi:10.1021/jf061471t. PMID 17090106.

- ^ a b c Friedman M, McDonald GM, Filadelfi-Keszi M (22 September 2010). "Potato Glycoalkaloids: Chemistry, Analysis, Safety, and Plant Physiology". Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 16 (1): 55–132. doi:10.1080/07352689709701946.

- ^ a b Itkin M, Rogachev I, Alkan N, et al. (December 2011). "GLYCOALKALOID METABOLISM1 Is Required for Steroidal Alkaloid Glycosylation and Prevention of Phytotoxicity in Tomato". The Plant Cell. 23 (12): 4507–4525. doi:10.1105/tpc.111.088732. PMC 3269880. PMID 22180624.

- ^ Ohyama K, Okawa A, Moriuchi Y, Fujimoto Y (May 2013). "Biosynthesis of steroidal alkaloids in Solanaceae plants: Involvement of an aldehyde intermediate during C-26 amination". Phytochemistry. 89: 26–31. Bibcode:2013PChem..89...26O. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.01.010. PMID 23473422.

- ^ Lachman J, Hamouz K, Orsak M, Pivec V( (2001). "Potato glycoalkaloids and their significance in plant protection and human nutrition – review". Rostlinna Vyroba – UZPI (Czech Republic). ISSN 0370-663X.

- ^ Chowański S, Adamski Z, Marciniak P, et al. (1 March 2016). "A Review of Bioinsecticidal Activity of Solanaceae Alkaloids". Toxins. 8 (3): 60. doi:10.3390/toxins8030060. PMC 4810205. PMID 26938561.

- ^ Hlywka JJ, Stephenson GR, Sears MK, Yada RY (November 1994). "Effects of insect damage on glycoalkaloid content in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 42 (11): 2545–2550. doi:10.1021/jf00047a032.

- ^ Bushway RJ, Ponnampalam R (July 1981). ".alpha.-Chaconine and .alpha.-solanine content of potato products and their stability during several modes of cooking". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 29 (4): 814–817. doi:10.1021/jf00106a033.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beier R (1990). Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Springer New York. ISBN 978-1-4612-7983-9.

- ^ a b Jadhav SJ, Sharma RP, Salunkhe DK (26 September 2008). "Naturally Occurring Toxic Alkaloids in Foods". CRC Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 9 (1): 21–104. doi:10.3109/10408448109059562. PMID 7018841.

- ^ a b Sc M, Th L (1984). "The toxicity and teratogenicity of Solanaceae glycoalkaloids, particularly those of the potato (Solanum tuberosum): a review". Food Technology in Australia. ISSN 0015-6647.

- ^ Wilson AM, McGann DF, Bushway RJ (February 1983). "Effect of Growth-Location and Length of Storage on Glycoalkaloid Content of Roadside-Stand Potatoes as Stored by Consumers". Journal of Food Protection. 46 (2): 119–121. doi:10.4315/0362-028X-46.2.119. PMID 30913609.

- ^ Haseena, R., Ganapathy, S., Pandiarajan, T., & Amirtham, D. (2019). Effect of storage methods on solanine content of potato tubers. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 8(6), 1677–1679.

- ^ Phillips B, Hughes J, Phillips J, et al. (May 1996). "A study of the toxic hazard that might be associated with the consumption of green potato tops". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 34 (5): 439–448. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(96)87354-6. PMID 8655092.

- ^ Tice R (February 1998). Review of toxicological literature (PDF) (PhD Thesis).

- ^ a b c Maga JA, Fitzpatrick TJ (29 September 2009). "Potato glycoalkaloids". CRC Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 12 (4): 371–405. doi:10.1080/10408398009527281. PMID 6996922.

- ^ Cheeke PR (1989). Toxicants of Plant Origin: Alkaloids. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-6990-2.

- ^ Friedman M, Roitman JN, Kozukue N (7 May 2003). "Glycoalkaloid and calystegine contents of eight potato cultivars". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (10): 2964–73. doi:10.1021/jf021146f. PMID 12720378.

- ^ Toxicological evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. World Health Organization. 1993. ISBN 9241660325.

- ^ Willimott SG (1933). "An investigation of solanine poisoning". The Analyst. 58 (689): 431. Bibcode:1933Ana....58..431W. doi:10.1039/AN9335800431.

- ^ McMillan M, Thompson JC (April 1979). "An outbreak of suspected solanine poisoning in schoolboys: Examinations of criteria of solanine poisoning". The Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 48 (190): 227–43. PMID 504549.

- ^ Hopkins J (1 April 1995). "The glycoalkaloids: Naturally of interest (but a hot potato?)". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 33 (4): 323–328. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(94)00148-H. ISSN 0278-6915. PMID 7737605.

- ^ Najm AA, Haj Seyed Hadi MR, F F, et al. (2012). "Effect of Integrated Management of Nitrogen Fertilizer and Cattle Manure on the Leaf Chlorophyll, Yield, and Tube Glycoalkaloids of Agria Potato". Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. 43 (6): 912–923. Bibcode:2012CSSPA..43..912N. doi:10.1080/00103624.2012.653027. S2CID 98187389.

- ^ Tajner-Czopek A, Jarych-Szyszka M, Fazeli F, Lisinska G (2008). "Changes in glycoalkaloids content 'of potatoes destined for consumption". Food Chemistry. 106 (2): 706–711. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.06.034.

- ^ "Solanine poisoning". BMJ. 2 (6203): 1458–9. 1979. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6203.1458-a. PMC 1597169. PMID 526812.

- ^ Alexander RF, Forbes GB, Hawkins ES (1948). "A Fatal Case of Solanine Poisoning". BMJ. 2 (4575): 518. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4575.518. PMC 2091497. PMID 18881287.

- ^ McGee H (29 July 2009). "Accused, Yes, but Probably Not a Killer". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

External links

edit- a-Chaconine and a-Solanine, Review of Toxicological Literature

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: 002875 – "Green tubers and sprouts"