Hostility is seen as a form of emotionally charged aggressive behavior. In everyday speech, it is more commonly used as a synonym for anger and aggression.

| Hostility | |

|---|---|

| |

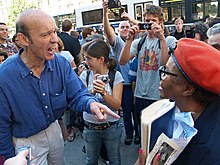

| Two people in a heated argument in New York City | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

It appears in several psychological theories. For instance it is a facet of neuroticism in the NEO PI, and forms part of personal construct psychology, developed by George Kelly.

Hostility/hospitality

editFor hunter gatherers, every stranger from outside the small tribal group was a potential source of hostility.[1] Similarly, in archaic Greece, every community was in a state of hostility, latent or overt, with every other community - something only gradually tempered by the rights and duties of hospitality.[2]

Tensions between the two poles of hostility and hospitality remain a potent force in the 21st century world.[3]

Us/them

editRobert Sapolsky argues that the tendency to form in-groups and out-groups of Us and Them, and to direct hostility at the latter, is inherent in humans.[4] He also explores the possibility raised by Samuel Bowles that intra-group hostility is reduced when greater hostility is directed at Thems,[5] something exploited by insecure leaders when they mobilise external conflicts so as to reduce in-group hostility towards themselves.[6]

Non-verbal indicators

editAutomatic mental functioning suggests that among universal human indicators of hostility are the grinding or gnashing of teeth, the clenching and shaking of fists, and grimacing.[7] Desmond Morris would add stamping and thumping.[8]

The Haka represents a ritualised set of such non-verbal signs of hostility.[9]

Kelly's model

editIn psychological terms, George Kelly considered hostility as the attempt to extort validating evidence from the environment to confirm types of social prediction, constructs, that have failed.[10] Instead of reconstructing their constructs to meet disconfirmations with better predictions, the hostile person attempts to force or coerce the world to fit their view, even if this is a forlorn hope, and even if it entails emotional expenditure and/or harm to self or others.[11]

In this sense hostility is a form of psychological extortion - an attempt to force reality to produce the desired feedback,[12] even by acting out in bullying by individuals and groups in various social contexts, in order that preconceptions become ever more widely validated. Kelly's theory of cognitive hostility thus forms a parallel to Leon Festinger's view that there is an inherent impulse to reduce cognitive dissonance.[13]

While challenging reality can be a useful part of life, and persistence in the face of failure can be a valuable trait (for instance in invention or discovery [citation needed]), in the case of hostility it is argued that evidence is not being accurately assessed but rather forced into a Procrustean mould in order to maintain one's belief systems and avoid having one's identity challenged.[14] Instead it is claimed that hostility shows evidence of suppression or denial, and is "deleted" from awareness - unfavorable evidence which might suggest that a prior belief is flawed is to various degrees ignored and willfully avoided.[15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ J Diamond, The World Until Yesterday (Penguin 2013) p. 50 and p. 290

- ^ M I Finley, The World of Odysseus (Pelican 1967) p. 113-4 and p. 116-7

- ^ K Thorpe ed., Hospitality and Hostility in the Multilingual Global Village (2014) p. 2-7

- ^ R Sapolsky, Behave (London 2018) Ch 11 384-424

- ^ R Sapolsky, Behave (London 2018) p. 45

- ^ E Smith, Social Psychology (Hove 2007) p. 493

- ^ D Maclean, The Triune Brain in Evolution (London 1990) p. 460

- ^ D Morris, The Naked Ape Trilogy (London 1988) p. 109

- ^ R Sapolsky, Behave (London 2018) p. 17

- ^ D Lester, Theories of Personality (1995) p. 52

- ^ D Lester, Theories of Personality (1995) p. 52-4

- ^ G Claxton, Live and Learn (Bristol 1984) p. 132 and p. 250

- ^ D Lester, Theories of Personality (1995) p. 76

- ^ D Lester, Theories of Personality (1995) p. 52-3

- ^ G Claxton, Live and Learn (Bristol 1984) p. 14 and p. 19