France entered World War I when Germany declared war on 3 August 1914.

World War I largely arose from a conflict between two alliances: the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy) and the Triple Entente (France, Russia, and Britain). France had had a military alliance with Russia since 1894, designed primarily to neutralize the German threat to both countries. Germany had a military alliance with Austria-Hungary.

In June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated. The government of Austria-Hungary decided to destroy Serbia once and for all for stirring up trouble among ethnic Slavs. Germany secretly gave Austria-Hungary a blank check, promising to support it militarily no matter what it decided. Both countries wanted a localized war, Austria-Hungary versus Serbia.

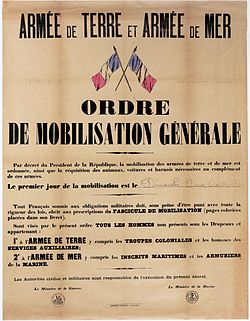

Russia decided to intervene to protect Serbia due to its interest in the Balkan region and its desire to gain an advantage over Austria-Hungary. The Tsar had the support of the President of France, who otherwise was hardly involved. Russia mobilized its army against Austria-Hungary. France mobilized its army. Germany declared war on Russia and France, and invaded France through Belgium. Britain had an understanding and military and naval planning agreements with France, but no formal treaty obligations. London felt British interest required a defence of France. Britain did have a treaty obligation toward Belgium, and that was used as the official reason Britain declared war on Germany. Japan, allied with Britain, was not obligated to go to war but did so to gain spoils. Turkey joined the Central Powers. Italy, instead of joining Germany and Austria-Hungary with whom it had treaties, entered the war on the side of the Allies in 1915. The United States tried unsuccessfully to broker peace negotiations, and entered the war on the Allied side in April 1917. After very heavy losses on both sides, the Allies were decisively victorious, and divided the spoils of victory, such as the German colonies and much of the territory of the Ottoman Empire. The Austro-Hungarian, German, Russian and Ottoman Empires disintegrated.[1]

Diplomatic background

editBy the late 1880s, Bismarck's League of the Three Emperors was in disarray; although Germany remained closely allied to Austria-Hungary, there was growing friction between Russia and Austria-Hungary over the Balkans. Angered by Austria's role in the Treaty of Berlin (1878), which forced Russia to withdraw from Bulgaria, Tsar Alexander III refused to renew the treaty in 1887.[2] Bismarck, in the hope of making the Tsar more amenable to his wishes, had forbidden German banks to lend money to Russia. French bankers quickly replaced the Germans in financing Russia, and helped to speed Russian industrialization. The Russians had borrowed around 500 million francs by 1888. Bismarck signed a Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1887, but after Bismarck's fall from power in 1890 Kaiser William II refused Russia's request to renew it.

The advantage of a Franco-Russian alliance was clear to all Frenchmen: France would not be alone against Germany, for it promised a two-front war. Formal visits were exchanged between the two powers in 1890 and 1891, and the Russian Tsar saluted the French national anthem, La Marseillaise. The Franco-Russian alliance was announced in 1894. This diplomatic coup was followed by a secret agreement with Italy, allowing the Italians a free hand to expand in Tripoli (modern Libya, then still under Turkish rule). In return, Italy promised she would remain non-belligerent against France in any future war. Meanwhile, as Britain became increasingly anxious over the German naval buildup and industrial rivalry, agreement with France became increasingly attractive.

France competed with Britain, and to a lesser extent with Italy, for control of Africa. There was constant friction between Britain and France over borders between their respective African colonies (see the Fashoda Incident). The French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé was aware that France could not progress if she was in conflict with Germany in Europe and Britain in Africa, and so recalled Captain Marchand's expeditionary force from Fashoda, despite popular protests. This paved the way for Britain joining France in World War I.

Edward VII's visit to Paris in 1903 stilled anti-British feeling in France, and prepared the way for the Entente Cordiale. Initially however, a colonial agreement against the Kaiser's aggressive foreign policy deepened rather than destroyed the bond between the two countries. The Moroccan Crises of 1905 and 1911 encouraged both countries to embark on a series of secret military negotiations in the case of war with Germany. However, British Foreign Minister Edward Grey realized the risk that small conflicts between Paris and Berlin could escalate out of control. Working with little supervision from the British Prime Minister or Cabinet, Grey deliberately played a mediating role, trying to calm both sides and thereby maintain a peaceful balance of power. He refused to make permanent commitments to France. He approved military staff talks with France in 1905, thereby suggesting, but not promising, that if war broke out Britain would favor France over Germany. In 1911, when there was a second Franco-German clash over Morocco, Grey tried to moderate the French while supporting Germany in its demand for compensation. There was little risk that Britain would have conflicts with anyone leading to war. The Royal Navy remained dominant in world affairs, and remained a high spending priority for the British government. The British Army was small, although plans to send an expeditionary force to France had been developed since the Haldane Reforms. From 1907 through 1914, the French and British armies collaborated on highly detailed plans for mobilizing a British Expeditionary Force of 100,000 combat troops to be very quickly moved to France, and sent to the front in less than two weeks.[3] Grey insisted that world peace was in the best interests of Britain and the British Empire.[4]

France could strengthen its position in the event of war by forming new alliances or by enlisting more young men. It used both methods.[5] Russia was firmly in the same camp, and Britain was almost ready to join. In 1913 the controversial "three year law" extended the term of conscription for French draftees from two to three years. Previously young men were in training at ages 21 and 22 then joined the reserves; now they were in training at ages 20, 21, and 22.[6] This was later lowered even more.

When the war began in 1914, France could only win if Britain joined with France and Russia to stop Germany. There was no binding treaty between Britain and France, and no moral commitment on the British part to go to war on France's behalf. The Liberal government of Britain was pacifistic, and also extremely legalistic, so that German violation of Belgium neutrality – treating it like a scrap of paper – helped mobilize party members to support the war effort. The decisive factors were twofold, Britain felt a sense of obligation to defend France, and the Liberal Government realized that unless it did so, it would collapse either into a coalition, or yield control to the more militaristic Conservative Party. Either option would likely ruin the Liberal Party. When the German army invaded Belgium, not only was neutrality violated, but France was threatened with defeat, so the British government went to war.[7]

Mounting international tensions and the arms race led to the need to increase conscription from two to three years. Socialists, led by Jean Jaurès, deeply believed that war was a capitalist plot and could never be beneficial to the working man. They worked hard to defeat the conscription proposal, often in cooperation with middle-class pacifists and women's groups, but were outvoted.[8]

Attitudes toward Germany

editThe critical issue for France was its relationship with Germany. Paris had relatively little involvement in the Balkan crisis that launched the war, paying little attention to Serbia, Austria or the Ottoman Empire. However, a series of unpleasant diplomatic confrontations with Germany soured relationships. The defeat in 1870–71 rankled France, especially the loss of Alsace and Lorraine. French revanchism was not a major cause of war in 1914 because it faded after 1880. J.F.V. Keiger says, "By the 1880s Franco-German relations were relatively good."[9] Although the issue of Alsace-Lorraine faded in importance after 1880, the rapid growth in the population and economy of Germany left France increasingly far behind. It was obvious that Germany could field more soldiers and build more heavy weapons.

In the 1890s relationships remained good since Germany supported France during its difficulties with Britain over African colonies. Any lingering harmony, however, collapsed in 1905 by Germany taking an aggressively hostile position on French claims to Morocco. There was talk of war, and France strengthened its ties with Britain and Russia.[10] Even critics of French imperialism, such as Georges Clemenceau, had become impatient with Berlin. Raymond Poincaré's speeches as Prime Minister in 1912, and then as president in 1913–14, were similarly firm and drew widespread support across the political spectrum.[11]

Only the socialists were holdouts, warning that war was a capitalist ploy and should be avoided by the working class. In July 1914, socialist leader Jean Jaurès obtained a vote against war from the French Socialist Party Congress. 1,690 delegates supported a general strike against the war if the German socialists followed suit, with 1,174 opposed.[12] However Jaurès was assassinated on 31 July, and the socialist parties in both France and Germany – as well as most other countries – strongly supported their national war effort in the first year.[13]

Main players

editAs in all the major powers, a handful of men made the critical decisions in the summer of 1914.[14] As the French ambassador to Germany from 1907 to 1914, Jules Cambon worked hard to secure a friendly détente. He was frustrated by French leaders such as Raymond Poincaré, who decided Berlin was trying to weaken the Triple Entente of France, Russia and Britain, and was not sincere in seeking peace. Apart from Cambron the French leadership believed that war was inevitable.[15]

President Raymond Poincaré was the most important decision maker, a highly skilled lawyer with a dominant personality and a hatred for Germany. He increasingly took charge of foreign affairs, but often was indecisive. René Viviani became Prime Minister and Foreign Minister in spring 1914. He was a cautious moderate but was profoundly ignorant of foreign affairs and baffled by what was going on. The main decisions were made by the foreign office and increasingly by the president. The ambassador to Russia, Maurice Paléologue, hated Germany and reassured Russia that France would fight alongside it against Germany.[16]

The central policy goal for Poincaré was maintaining the close alliance with Russia, which he achieved by a week-long visit to St. Petersburg in mid-July 1914. French and German leaders were closely watching the rapid rise in Russian military and economic power and capability. For the Germans, that deepened the worry often expressed by the Kaiser that Germany was being surrounded by enemies whose power was growing.[17] One implication was that time was against them, and a war soon would be more advantageous for Germany than war later. For the French, there was a growing fear that Russia would become significantly more powerful than France and become more independent of France, possibly even returning to its old military alliance with Germany. The implication was that a war sooner could count on the Russian alliance, but the longer it waited, the greater the likelihood of a Russian alliance with Germany that would doom France.[18]

July crisis

editOn 28 June 1914, the world was surprised, but not especially alarmed, by news of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.[19] The July crisis began on 23 July 1914 with the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia, containing brutal terms intended to inspire rejection. The crisis was caused not by the assassination but rather by the decision in Vienna to use it as a pretext for a war with Serbia that many in the Austrian and Hungarian governments had long advocated.[20] A year before, it had been planned that French President Raymond Poincaré would visit St Petersburg in July 1914 to meet Tsar Nicholas II. The Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, Count Berchtold, decided that it was too dangerous for Austria-Hungary to present the ultimatum while the Franco-Russian summit was in progress. He decided to wait until Poincaré was on board the battleship that would take him home so that he could not easily co-ordinate with Russia.[21]

At the time of the St Petersburg summit, there were rumours but little hard evidence that Vienna might use the assassination to start a war with Serbia. War did not appear imminent when President Poincaré and his new Prime Minister René Viviani departed by ship for St Petersburg on 15 July, arrived on 20 July and departed for home on 23 July. The meetings were centrally concerned with the crisis unfolding in central Europe. Although Viviani was also foreign minister, he was unfamiliar with foreign affairs and said little. Poincaré was fully in charge of the French side of the discussions. Throughout the visit, he was aggressively hostile toward Germany and cared little for Serbia or Austria-Hungary.[22][23]

The French and the Russians agreed that their alliance extended to supporting Serbia against Austria, confirming the already-established policy behind the Balkan inception scenario. As Christopher Clark noted, "Poincaré had come to preach the gospel of firmness and his words had fallen on ready ears. Firmness in this context meant an intransigent opposition to any Austrian measure against Serbia. At no point do the sources suggest that Poincaré or his Russian interlocutors gave any thought whatsoever to what measures Austria-Hungary might legitimately be entitled to take in the aftermath of the assassinations".[24]

Vienna and Berlin both wanted to keep the confrontation localised to the Balkans so that Austria would be the only major power involved. They neglected to negotiate on that point and indeed systematically deceived the potential adversaries. Thus, the delivery of the Austrian ultimatum to Serbia was deliberately scheduled for a few hours after the departure of the French delegation from Russia on 23 July so that France and Russia could not co-ordinate their responses. There was a false assumption that if France were kept in the dark, it would still have a moderating influence and thus localise the war.[25]

Just the opposite took place: without co-ordination, Russia assumed it had France's full support and so Austria sabotaged its own hopes for localisation. In St Petersburg, most Russian leaders sensed that their national strength was gaining on Germany and Austria and so it would be prudent to wait until they were stronger. However, they decided that Russia would lose prestige and forfeit its chance to take a strong leadership role in the Balkans. They might be stronger in a future confrontation, but at present they had France as an ally, and the future was unpredictable. Thus, Tsar Nicholas II decided to mobilize on the southwestern flank against Austria to deter Vienna from an invasion of Serbia.[26]

Christopher Clark stated, "The Russian general mobilisation [of 30 July] was one of the most momentous decisions of the July crisis. This was the first of the general mobilisations. It came at the moment when the German government had not yet even declared the State of Impending War".[27] Germany now felt threatened and responded with her own mobilisation and declaration of war on 1 August 1914.[28]

All of those decisive moves and countermoves took place while Poincaré was slowly returning to Paris on board a battleship. Poincaré's attempts while afloat to communicate with Paris were blocked by the Germans, who jammed the radio messages between his ship and Paris.[29] When Vienna's ultimatum was presented to Serbia on 23 July, the French government was in the hands of Acting Premier Jean-Baptiste Bienvenu-Martin, the Minister of Justice, who was unfamiliar with foreign affairs. His inability to take decisions especially exasperated the Quai d'Orsay (the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs). Senior diplomat Philippe Berthelot complained that France was doing nothing while Europe was threatened with the prospect of war.[30] Realising that Poincaré was practically incommunicado, the French military command began issuing orders in preparation for its own mobilization in defense against Germany, and it ordered French troops to withdraw 10 km (6.2 mi) from the German border not avoid being provocative. The French war plan called for an immediate invasion of Alsace-Lorraine and never expected that the main German attack would come immediately and come far to the north, through neutral Belgium.[31]

France and Russia agreed that there must not be an ultimatum. On 21 July, the Russian Foreign Minister warned the German ambassador to Russia, "Russia would not be able to tolerate Austria-Hungary's using threatening language to Serbia or taking military measures". The leaders in Berlin discounted that threat of war and failed to pass on the message to Vienna for a week. German Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow noted that "there is certain to be some blustering in St Petersburg". German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg told his assistant that Britain and France did not realize that Germany would go to war if Russia mobilized. He thought London saw a German "bluff" and was responding with a "counterbluff".[32]

Political scientist James Fearon argued from this episode that the Germans believed Russia to be expressing greater verbal support for Serbia than it would actually provide to pressure Germany and Austria-Hungary to accept some Russian demands in negotiation. Meanwhile, Berlin was downplaying its actual strong support for Vienna to avoid appearing the aggressor, which would alienate German socialists.[33]

France's passive role

editFrance played only a small largely passive role in the diplomatic crisis of July 1914. Its top leaders were out of the country and mostly out of contact with breaking reports from July 15 to July 29, when most of the critical decisions were taken.[34][35] Austria and Germany deliberately acted to prevent the French and Russian leadership from communicating during the last week in July. But this made little difference as French policy in strong support of Russia had been locked in. Germany realized that a war with Russia meant a war with France, and so its war plans called for an immediate attack on France – through Belgium – hoping for a quick victory before the slow-moving Russians could become a factor. France was a major military and diplomatic player before and after the July crisis, and every power paid close attention to its role. Historian Joachim Remak says:

- The nation that...can still be held least responsible for the outbreak of the war is France. This is so even if we bear in mind all the revisions of historical judgments, and all the revisions of these revisions, to which we have now been treated....The French, in 1914, entered the war because they had no alternative. The Germans had attacked them. History can be very simple at times.[36]

While other countries published compendia of diplomatic correspondence, seeking to establish justification for their own entry into the war, and cast blame on other actors for the outbreak of war within days of the outbreak of hostilities, France held back.[37] The first of these color books to appear, was the German White Book[38] which appeared on 4 August 1914, the same day as Britain's war declaration[39] but France held back for months, only releasing the French Yellow Book in response on 1 December 1914.[39]

Leaders

edit- Raymond Poincaré – President of France

- René Viviani – Prime Minister of France (13 June 1914 – 29 October 1915)

- Aristide Briand – Prime Minister of France (29 October 1915 – 20 March 1917)

- Alexandre Ribot – Prime Minister of France (20 March 1917 – 12 September 1917)

- Paul Painlevé – Prime Minister of France (12 September 1917 – 16 November 1917)

- Georges Clemenceau – Prime Minister of France (from 16 November 1917)

- General (later Marshal) Joseph Joffre – Commander-in-Chief of the French Army (3 August 1914 – 13 December 1916)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ For a short overview see David Fromkin, Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914? (2004).

- ^ Lieven 2016, p. 81.

- ^ Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., The Politics of Grand Strategy: France and Britain Prepare for War, 1904–1914. (1969) pp 313–17.

- ^ Thomas G. Otte, "'Almost a law of nature'? Sir Edward Grey, the foreign office, and the balance of power in Europe, 1905–12." Diplomacy and Statecraft 14.2 (2003): 77–118.

- ^ James D. Morrow, "Arms versus Allies: Trade-offs in the Search for Security." International Organization 47.2 (1993): 207–233. online

- ^ Gerd Krumeich, Armaments and Politics in France on the Eve of the First World War: The Introduction of Three-Year Conscription, 1913–1914 (1985).

- ^ Trevor Wilson, "Britain's ‘Moral Commitment’ to France in August 1914." History 64.212 (1979): 380–390. online

- ^ David M. Rowe, "Globalization, conscription, and anti-militarism in pre-World War I Europe." in Lars Mjoset and Stephen Van Holde, eds. The Comparative Study of Conscription in the Armed Forces (Emerald Group, 2002) pp. 145–170.

- ^ J.F.V. Keiger, France and the World since 1870 (2001) pp 112–120, quoting p 113.

- ^ J.F.V. Keiger, France and the World since 1870 (2001) pp 112–17.

- ^ John Horne (2012). A Companion to World War I. John Wiley & Sons. p. 12. ISBN 9781119968702.

- ^ Hall Gardner (2016). The Failure to Prevent World War I: The Unexpected Armageddon. Routledge. pp. 212–13. ISBN 9781317032175.

- ^ Barbara W. Tuchman, "The Death of Jaurès", chapter 8 of The Proud Tower – A portrait of the world before the War: 1890–1914 (1966) pp. 451–515.

- ^ T.G. Otte, July Crisis: The world's descent into war, summer 1914 (2014) pp xvii–xxii.

- ^ John Keiger, "Jules Cambon and Franco-German Détente, 1907–1914." The Historical Journal 26.3 (1983): 641–659.

- ^ William A. Renzi, "Who Composed 'Sazonov's Thirteen Points'? A Re-Examination of Russia's War Aims of 1914." American Historical Review 88.2 (1983): 347–357. online.

- ^ Jo Groebel and Robert A. Hinde, ed. (1989). Aggression and War: Their Biological and Social Bases. Cambridge University Press. p. 196. ISBN 9780521358712.

- ^ Otte, July Crisis (2014) pp 99, 135–36.

- ^ David Fromkin, Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914? (2004) p. 138.

- ^ Fromkin, p. 264.

- ^ Fromkin, pp 168–169.

- ^ Sidney Fay, Origins of the World War (1934) 2:277-86.

- ^ Sean McMeekin, July 1914 (2014) pp 145–76 covers the visit day-by-day.

- ^ Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers (2012) pp. 449–50.

- ^ John F. V. Keiger, France and the origins of the First World War (1983) pp 156–57.

- ^ Jack S. Levy, and William Mulligan, "Shifting power, preventive logic, and the response of the target: Germany, Russia, and the First World War." Journal of Strategic Studies 40.5 (2017): 731–769.

- ^ Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2013). p 509.

- ^ W. Bruce Lincoln, Passage Through Armageddon: The Russians in War and Revolution, 1914–1918 (1986)

- ^ Fromkin, p. 194.

- ^ Fromkin, p 190.

- ^ Keiger, France and the origins of the First World War (1983) pp 152–54.

- ^ Konrad Jarausch, "The Illusion of Limited War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg's Calculated Risk, July 1914" Central European History (1969) 2#1 pp 48–76. online

- ^ Fearon, James D. (Summer 1995). "Rationalist Explanations for War" (PDF). International Organization. 49 (3): 397–98. doi:10.1017/S0020818300033324. S2CID 38573183.

- ^ John F. V. Keiger, France and the origins of the First World War (1983) pp 146–154.

- ^ T. G. Otte, July Crisis: The World's Descent into War, Summer 1914 (2014). pp 198–209.

- ^ Joachim Remak, "1914—The Third Balkan War: Origins Reconsidered." Journal of Modern History 43.3 (1971): 354–366 at pp 354–55.

- ^ Hartwig, Matthias (12 May 2014). "Colour books". In Bernhardt, Rudolf; Bindschedler, Rudolf; Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (eds.). Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Vol. 9 International Relations and Legal Cooperation in General Diplomacy and Consular Relations. Amsterdam: North-Holland. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4832-5699-3. OCLC 769268852.

- ^ von Mach, Edmund (1916). Official Diplomatic Documents Relating to the Outbreak of the European War: With Photographic Reproductions of Official Editions of the Documents (Blue, White, Yellow, Etc., Books). New York: Macmillan. p. 7. LCCN 16019222. OCLC 651023684.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Bernadotte E. (1 April 1937). "France and the Outbreak of the World War". Foreign Affairs. 26 (3). Council on Foreign Relations: 516–536. doi:10.2307/20028790. JSTOR 20028790. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018.

Sources

edit- Lieven, Dominic (2016). Towards the Flame: Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Russia. Penguin. ISBN 978-0141399744.

Further reading

edit- Albertini, Luigi. The Origins of the War of 1914 (3 vol 1952). vol 2 online covers July 1914

- Albrecht-Carrié, René. A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna (1958), 736pp; basic survey

- Andrew, Christopher. "France and the Making of the Entente Cordiale." Historical Journal 10#1 (1967): 89–105. online.

- Andrew, Christopher. "France and the Making of the Entente Cordiale." Historical Journal 10#1 (1967): 89–105. online.

- Bell, P.M.H. France and Britain, 1900–1940: Entente and Estrangement (1996)

- Brandenburg, Erich. (1927) From Bismarck to the World War: A History of German Foreign Policy 1870–1914 (1927) online Archived 2017-03-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- Brogan, D.W. The development of modern France (1870–1939) (1949) pp 432–62.online free

- Bury, J.P.T. "Diplomatic History 1900–1912, in C. L. Mowat, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History: Vol. XII: The Shifting Balance of World Forces 1898–1945 (2nd ed. 1968) online pp 112–139.

- Cabanes Bruno. August 1914: France, the Great War, and a Month That Changed the World Forever (2016) argues that the extremely high casualty rate in very first month of fighting permanently transformed France.

- Carroll, E. Malcolm, French Public Opinion and Foreign Affairs 1870–1914 (1931)online

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2013) excerpt

- Sleepwalkers lecture by Clark. online

- Doughty, Robert A. "France" in Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig, eds. War Planning 1914 (2014) pp 143–74.

- Evans, R. J. W.; von Strandmann, Hartmut Pogge, eds. (1988). The Coming of the First World War. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780191500596. Essays by scholars.

- Farrar, Marjorie M. "Politics versus patriotism: Alexandre Millerand as French minister of war." French Historical Studies 11.4 (1980): 577–609. online, war minister in 1912-13 and late 1914.

- Fay, Sidney B. The Origins of the World War (2 vols in one. 2nd ed. 1930). online, passim

- Fromkin, David. Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914? (2004).

- Gooch, G.P. Franco-German Relations 1871–1914 (1923). 72pp

- Hamilton, Richard F. and Holger H. Herwig, eds. Decisions for War, 1914–1917 (2004), scholarly essays on Serbia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France, Britain, Japan, Ottoman Empire, Italy, the United States, Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece.

- Hensel, Paul R. "The Evolution of the Franco-German Rivalry" in William R. Thompson, ed. Great power rivalries (1999) pp 86–124 online

- Herweg, Holger H., and Neil Heyman. Biographical Dictionary of World War I (1982).

- Hunter, John C. "The Problem of the French Birth Rate on the Eve of World War I" French Historical Studies 2#4 (1962), pp. 490–503 online

- Hutton, Patrick H. et al. Historical Dictionary of the Third French Republic, 1870–1940 (2 vol 1986) online edition vol 1[permanent dead link]; online edition vol 2[permanent dead link]

- Joll, James; Martel, Gordon (2013). The Origins of the First World War (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317875352.

- Kennan, George Frost. The fateful alliance: France, Russia, and the coming of the First World War (1984) online free to borrow; covers 1890 to 1894.

- Keiger, John. "Jules Cambon and Franco-German Détente, 1907–1914." Historical Journal 26.3 (1983): 641–659.

- Keiger, John F. V. (1983). France and the origins of the First World War. Macmillan. ISBN 9780333285527.

- Keiger, J.F.V. France and the World since 1870 (2001)

- Kennedy, Paul M., ed. (2014) [1979]. The War Plans of the Great Powers: 1880-1914. Routledge. ISBN 9781317702511.

- Kiesling, Eugenia C. "France" in Richard F. Hamilton, and Holger H. Herwig, eds. Decisions for War, 1914-1917 (2004), pp 227–65.

- McMeekin, Sean. July 1914: Countdown to War (2014) scholarly account, day-by-day excerpt

- MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. ISBN 9780812994704.; major scholarly overview

- Mayeur, Jean-Marie, and Madeleine Rebérioux. The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871-1914 (The Cambridge History of Modern France) (1988) excerpt

- Neiberg, Michael S. Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I (2011), on public opinion

- Otte, T. G. July Crisis: The World's Descent into War, Summer 1914 (Cambridge UP, 2014). online review

- Paddock, Troy R. E. A Call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War (2004) online Archived 2019-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Pratt, Edwin A. The rise of rail-power in war and conquest, 1833–1914 (1915) online

- Ralston, David R. The Army of the Republic. The Place of the Military in the Political Evolution of France 1871–1914 (1967).

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1991), comprehensive survey

- Schmitt, Bernadotte E. The coming of the war, 1914 (2 vol 1930) comprehensive history online vol 1; online vol 2, esp vol 2 ch 20 pp 334–382

- Scott, Jonathan French. Five Weeks: The Surge of Public Opinion on the Eve of the Great War (1927) online Archived 2019-07-21 at the Wayback Machine. especially ch 8: "Fear, Suspicion, and Resolution in France" pp 179–206

- Seager, Frederic H. "The Alsace-Lorraine Question in France, 1871–1914." in Charles K. Warner, ed., From the Ancien Régime to the Popular Front (1969): 111–126.

- Sedgwick, Alexander. The Third French Republic, 1870–1914 (1968) online edition Archived 2010-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Schuman, Frederick L. War and diplomacy in the French Republic; an inquiry into political motivations and the control of foreign policy (1931) online Archived 2018-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Stevenson, David. "War by timetable? The railway race before 1914." Past & Present 162 (1999): 163–194. France vs Germany online

- Stowell, Ellery Cory. The Diplomacy of the War of 1914 (1915) 728 pages online free

- Strachan, Hew Francis Anthony (2004). The First World War. Viking.

- Stuart, Graham H. French foreign policy from Fashoda to Serajevo (1898–1914) (1921) 365pp online

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 (1954) online free

- Trachtenberg, Marc. "The Meaning of Mobilization in 1914" International Security 15#3 (1991) pp. 120–150 online

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1996) 816pp

- Williamson Jr., Samuel R. "German Perceptions of the Triple Entente after 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered" Foreign Policy Analysis 7.2 (2011): 205–214.

- Wright, Gordon. Raymond Poincaré and the French presidency 1967).

Historiography

edit- Cornelissen, Christoph, and Arndt Weinrich, eds. Writing the Great War – The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present (2020) free download; full coverage for major countries.

- Hewitson, Mark. "Germany and France before the First World War: a reassessment of Wilhelmine foreign policy." English Historical Review 115.462 (2000): 570–606; argues Germany had a growing sense of military superiority. online

- Horne, John, ed. A Companion to World War I (2012) 38 topics essays by scholars

- Kramer, Alan. "Recent Historiography of the First World War – Part I", Journal of Modern European History (Feb. 2014) 12#1 pp 5–27; "Recent Historiography of the First World War (Part II)", (May 2014) 12#2 pp 155–174.

- Loez, André, and Nicolas Mariot. "Le centenaire de la Grande Guerre: premier tour d'horizon historiographique." Revue française de science politique (2014) 64#3 512–518. online

- Mombauer, Annika. "Guilt or Responsibility? The Hundred-Year Debate on the Origins of World War I." Central European History 48.4 (2015): 541–564.

- Mulligan, William. "The Trial Continues: New Directions in the Study of the Origins of the First World War." English Historical Review (2014) 129#538 pp: 639–666.

- Winter, Jay. and Antoine Prost eds. The Great War in History: Debates and Controversies, 1914 to the Present (2005)

Primary sources

edit- Albertini, Luigi. The Origins of the War of 1914 (3 vol 1952). vol 3 pp 66–111.

- Gooch, G.P. Recent revelations of European diplomacy (1928) pp 269–330.

- United States. War Dept. General Staff. Strength and organization of the armies of France, Germany, Austria, Russia, England, Italy, Mexico and Japan (showing conditions in July, 1914) (1916) online

- Major 1914 documents from BYU online