Biomineralising polychaetes are polychaetes that produce minerals to harden or stiffen their own tissues (biomineralize).

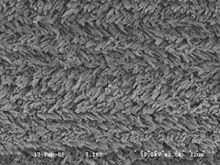

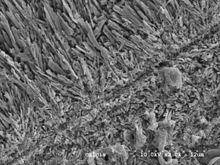

The most important biomineralizing polychaetes are serpulids, sabellids and cirratulids. They secrete tubes of calcium carbonate. Serpulids have most advanced biomineralization system among the annelids. Serpulids possess very diverse tube ultrastructures. Serpulid tubes are composed of aragonite, calcite or mixture of both polymorphs. In addition to the tubes, some serpulid species secrete calcareous opercula. Some sabellids and cirratulids can secrete aragonitic tubes. Sabellid and cirratulid tubes have a spherulitic prismatic ultrastructure. There are thin organic sheets in serpulid tube mineral structures. These sheets have evolved as an adaptation to strengthen the mechanical properties of the tubes.[1][2][3][4][5] Fossil and present-day cirratulid bioconstructors have been confirmed to be the only known occurrence of double-phased biomineralization processes in the animal kingdom.[6]

References

edit- ^ Vinn, O. (2009). "The ultrastructure of calcareous cirratulid (Polychaeta, Annelida) tubes" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (2): 153–156. doi:10.3176/earth.2009.2.06. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ^ Vinn, O.; Kirsimäe, K.; ten Hove, H.A. (2009). "Tube ultrastructure of Pomatoceros americanus (Polychaeta, Serpulidae): implications for the tube formation of serpulids" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (2): 148–152. doi:10.3176/earth.2009.2.05. Retrieved 2012-09-17.

- ^ Vinn, O.; ten Hove, H.A.; Mutvei, H.; Kirsimäe, K. (2008). "Ultrastructure and mineral composition of serpulid tubes (Polychaeta, Annelida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 154 (4): 633–650. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00421.x. Retrieved 2012-09-17.

- ^ Vinn, O.; ten Hove, H.A. (2011). "Microstructure and formation of the calcareous operculum in Pyrgopolon ctenactis and Spirobranchus giganteus (Annelida, Serpulidae)". Zoomorphology. 130 (3): 181–188. doi:10.1007/s00435-011-0133-0. S2CID 41765489. Retrieved 2012-09-17.

- ^ Vinn, O. (2013). "Occurrence formation and function of organic sheets in the mineral tube structures of Serpulidae (Polychaeta Annelida)". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e75330. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875330V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075330. PMC 3792063. PMID 24116035.

- ^ Guido A, D'Amico F, DeVries TJ, Kočí T, Collareta A, Bosio G, Sanfilippo R (2024). "Double-phased controlled and influenced biomineralization in marine invertebrates: The example of Miocene to recent reef-building polychaete cirratulids from southern Peru". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 639: 112060. Bibcode:2024PPP...63912060G. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112060. S2CID 267306998.