Adsorption is the adhesion[1] of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface.[2] This process creates a film of the adsorbate on the surface of the adsorbent. This process differs from absorption, in which a fluid (the absorbate) is dissolved by or permeates a liquid or solid (the absorbent).[3] While adsorption does often precede absorption, which involves the transfer of the absorbate into the volume of the absorbent material, alternatively, adsorption is distinctly a surface phenomenon, wherein the adsorbate does not penetrate through the material surface and into the bulk of the adsorbent.[4] The term sorption encompasses both adsorption and absorption, and desorption is the reverse of sorption.

adsorption: An increase in the concentration of a dissolved substance at the interface of a condensed and a liquid phase due to the operation of surface forces. Adsorption can also occur at the interface of a condensed and a gaseous phase. [5]

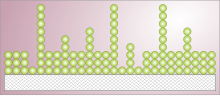

Like surface tension, adsorption is a consequence of surface energy. In a bulk material, all the bonding requirements (be they ionic, covalent or metallic) of the constituent atoms of the material are fulfilled by other atoms in the material. However, atoms on the surface of the adsorbent are not wholly surrounded by other adsorbent atoms and therefore can attract adsorbates. The exact nature of the bonding depends on the details of the species involved, but the adsorption process is generally classified as physisorption (characteristic of weak van der Waals forces) or chemisorption (characteristic of covalent bonding). It may also occur due to electrostatic attraction.[6][7] The nature of the adsorption can affect the structure of the adsorbed species. For example, polymer physisorption from solution can result in squashed structures on a surface.[8]

Adsorption is present in many natural, physical, biological and chemical systems and is widely used in industrial applications such as heterogeneous catalysts,[9][10] activated charcoal, capturing and using waste heat to provide cold water for air conditioning and other process requirements (adsorption chillers), synthetic resins, increasing storage capacity of carbide-derived carbons and water purification. Adsorption, ion exchange and chromatography are sorption processes in which certain adsorbates are selectively transferred from the fluid phase to the surface of insoluble, rigid particles suspended in a vessel or packed in a column. Pharmaceutical industry applications, which use adsorption as a means to prolong neurological exposure to specific drugs or parts thereof,[citation needed] are lesser known.

The word "adsorption" was coined in 1881 by German physicist Heinrich Kayser (1853–1940).[11]

Isotherms

editThe adsorption of gases and solutes is usually described through isotherms, that is, the amount of adsorbate on the adsorbent as a function of its pressure (if gas) or concentration (for liquid phase solutes) at constant temperature. The quantity adsorbed is nearly always normalized by the mass of the adsorbent to allow comparison of different materials. To date, 15 different isotherm models have been developed.[12]

Freundlich

editThe first mathematical fit to an isotherm was published by Freundlich and Kuster (1906) and is a purely empirical formula for gaseous adsorbates:

where is the mass of adsorbate adsorbed, is the mass of the adsorbent, is the pressure of adsorbate (this can be changed to concentration if investigating solution rather than gas), and and are empirical constants for each adsorbent–adsorbate pair at a given temperature. The function is not adequate at very high pressure because in reality has an asymptotic maximum as pressure increases without bound. As the temperature increases, the constants and change to reflect the empirical observation that the quantity adsorbed rises more slowly and higher pressures are required to saturate the surface.

Langmuir

editIrving Langmuir was the first to derive a scientifically based adsorption isotherm in 1918.[13] The model applies to gases adsorbed on solid surfaces. It is a semi-empirical isotherm with a kinetic basis and was derived based on statistical thermodynamics. It is the most common isotherm equation to use due to its simplicity and its ability to fit a variety of adsorption data. It is based on four assumptions:

- All of the adsorption sites are equivalent, and each site can only accommodate one molecule.

- The surface is energetically homogeneous, and adsorbed molecules do not interact.

- There are no phase transitions.

- At the maximum adsorption, only a monolayer is formed. Adsorption only occurs on localized sites on the surface, not with other adsorbates.

These four assumptions are seldom all true: there are always imperfections on the surface, adsorbed molecules are not necessarily inert, and the mechanism is clearly not the same for the first molecules to adsorb to a surface as for the last. The fourth condition is the most troublesome, as frequently more molecules will adsorb to the monolayer; this problem is addressed by the BET isotherm for relatively flat (non-microporous) surfaces. The Langmuir isotherm is nonetheless the first choice for most models of adsorption and has many applications in surface kinetics (usually called Langmuir–Hinshelwood kinetics) and thermodynamics.

Langmuir suggested that adsorption takes place through this mechanism: , where A is a gas molecule, and S is an adsorption site. The direct and inverse rate constants are k and k−1. If we define surface coverage, , as the fraction of the adsorption sites occupied, in the equilibrium we have:

or

where is the partial pressure of the gas or the molar concentration of the solution. For very low pressures , and for high pressures .

The value of is difficult to measure experimentally; usually, the adsorbate is a gas and the quantity adsorbed is given in moles, grams, or gas volumes at standard temperature and pressure (STP) per gram of adsorbent. If we call vmon the STP volume of adsorbate required to form a monolayer on the adsorbent (per gram of adsorbent), then , and we obtain an expression for a straight line:

Through its slope and y intercept we can obtain vmon and K, which are constants for each adsorbent–adsorbate pair at a given temperature. vmon is related to the number of adsorption sites through the ideal gas law. If we assume that the number of sites is just the whole area of the solid divided into the cross section of the adsorbate molecules, we can easily calculate the surface area of the adsorbent. The surface area of an adsorbent depends on its structure: the more pores it has, the greater the area, which has a big influence on reactions on surfaces.

If more than one gas adsorbs on the surface, we define as the fraction of empty sites, and we have:

Also, we can define as the fraction of the sites occupied by the j-th gas:

where i is each one of the gases that adsorb.

Note:

1) To choose between the Langmuir and Freundlich equations, the enthalpies of adsorption must be investigated.[14] While the Langmuir model assumes that the energy of adsorption remains constant with surface occupancy, the Freundlich equation is derived with the assumption that the heat of adsorption continually decrease as the binding sites are occupied.[15] The choice of the model based on best fitting of the data is a common misconception.[14]

2) The use of the linearized form of the Langmuir model is no longer common practice. Advances in computational power allowed for nonlinear regression to be performed quickly and with higher confidence since no data transformation is required.

BET

editOften molecules do form multilayers, that is, some are adsorbed on already adsorbed molecules, and the Langmuir isotherm is not valid. In 1938 Stephen Brunauer, Paul Emmett, and Edward Teller developed a model isotherm that takes that possibility into account. Their theory is called BET theory, after the initials in their last names. They modified Langmuir's mechanism as follows:

- A(g) + S ⇌ AS,

- A(g) + AS ⇌ A2S,

- A(g) + A2S ⇌ A3S and so on.

The derivation of the formula is more complicated than Langmuir's (see links for complete derivation). We obtain:

where x is the pressure divided by the vapor pressure for the adsorbate at that temperature (usually denoted ), v is the STP volume of adsorbed adsorbate, vmon is the STP volume of the amount of adsorbate required to form a monolayer, and c is the equilibrium constant K we used in Langmuir isotherm multiplied by the vapor pressure of the adsorbate. The key assumption used in deriving the BET equation that the successive heats of adsorption for all layers except the first are equal to the heat of condensation of the adsorbate.

The Langmuir isotherm is usually better for chemisorption, and the BET isotherm works better for physisorption for non-microporous surfaces.

Kisliuk

editIn other instances, molecular interactions between gas molecules previously adsorbed on a solid surface form significant interactions with gas molecules in the gaseous phases. Hence, adsorption of gas molecules to the surface is more likely to occur around gas molecules that are already present on the solid surface, rendering the Langmuir adsorption isotherm ineffective for the purposes of modelling. This effect was studied in a system where nitrogen was the adsorbate and tungsten was the adsorbent by Paul Kisliuk (1922–2008) in 1957.[16] To compensate for the increased probability of adsorption occurring around molecules present on the substrate surface, Kisliuk developed the precursor state theory, whereby molecules would enter a precursor state at the interface between the solid adsorbent and adsorbate in the gaseous phase. From here, adsorbate molecules would either adsorb to the adsorbent or desorb into the gaseous phase. The probability of adsorption occurring from the precursor state is dependent on the adsorbate's proximity to other adsorbate molecules that have already been adsorbed. If the adsorbate molecule in the precursor state is in close proximity to an adsorbate molecule that has already formed on the surface, it has a sticking probability reflected by the size of the SE constant and will either be adsorbed from the precursor state at a rate of kEC or will desorb into the gaseous phase at a rate of kES. If an adsorbate molecule enters the precursor state at a location that is remote from any other previously adsorbed adsorbate molecules, the sticking probability is reflected by the size of the SD constant.

These factors were included as part of a single constant termed a "sticking coefficient", kE, described below:

As SD is dictated by factors that are taken into account by the Langmuir model, SD can be assumed to be the adsorption rate constant. However, the rate constant for the Kisliuk model (R’) is different from that of the Langmuir model, as R’ is used to represent the impact of diffusion on monolayer formation and is proportional to the square root of the system's diffusion coefficient. The Kisliuk adsorption isotherm is written as follows, where θ(t) is fractional coverage of the adsorbent with adsorbate, and t is immersion time:

Solving for θ(t) yields:

Adsorption enthalpy

editAdsorption constants are equilibrium constants, therefore they obey the Van 't Hoff equation:

As can be seen in the formula, the variation of K must be isosteric, that is, at constant coverage. If we start from the BET isotherm and assume that the entropy change is the same for liquefaction and adsorption, we obtain

that is to say, adsorption is more exothermic than liquefaction.

Single-molecule explanation

editThe adsorption of ensemble molecules on a surface or interface can be divided into two processes: adsorption and desorption. If the adsorption rate wins the desorption rate, the molecules will accumulate over time giving the adsorption curve over time. If the desorption rate is larger, the number of molecules on the surface will decrease over time. The adsorption rate is dependent on the temperature, the diffusion rate of the solute (related to mean free path for pure gas), and the energy barrier between the molecule and the surface. The diffusion and key elements of the adsorption rate can be calculated using Fick's laws of diffusion and Einstein relation (kinetic theory). Under ideal conditions, when there is no energy barrier and all molecules that diffuse and collide with the surface get adsorbed, the number of molecules adsorbed at a surface of area on an infinite area surface can be directly integrated from Fick's second law differential equation to be:[17]

where is the surface area (unit m2), is the number concentration of the molecule in the bulk solution (unit #/m3), is the diffusion constant (unit m2/s), and is time (unit s). Further simulations and analysis of this equation[18] show that the square root dependence on the time is originated from the decrease of the concentrations near the surface under ideal adsorption conditions. Also, this equation only works for the beginning of the adsorption when a well-behaved concentration gradient forms near the surface. Correction on the reduction of the adsorption area and slowing down of the concentration gradient evolution have to be considered over a longer time.[19] Under real experimental conditions, the flow and the small adsorption area always make the adsorption rate faster than what this equation predicted, and the energy barrier will either accelerate this rate by surface attraction or slow it down by surface repulsion. Thus, the prediction from this equation is often a few to several orders of magnitude away from the experimental results. Under special cases, such as a very small adsorption area on a large surface, and under chemical equilibrium when there is no concentration gradience near the surface, this equation becomes useful to predict the adsorption rate with debatable special care to determine a specific value of in a particular measurement.[18]

The desorption of a molecule from the surface depends on the binding energy of the molecule to the surface and the temperature. The typical overall adsorption rate is thus often a combined result of the adsorption and desorption.

Quantum mechanical – thermodynamic modelling for surface area and porosity

editSince 1980 two theories were worked on to explain adsorption and obtain equations that work. These two are referred to as the chi hypothesis, the quantum mechanical derivation, and excess surface work (ESW).[20] Both these theories yield the same equation for flat surfaces:

where U is the unit step function. The definitions of the other symbols is as follows:

where "ads" stands for "adsorbed", "m" stands for "monolayer equivalence" and "vap" is reference to the vapor pressure of the liquid adsorptive at the same temperature as the solid sample. The unit function creates the definition of the molar energy of adsorption for the first adsorbed molecule by:

The plot of adsorbed versus is referred to as the chi plot. For flat surfaces, the slope of the chi plot yields the surface area. Empirically, this plot was noticed as being a very good fit to the isotherm by Michael Polanyi[21][22][23] and also by Jan Hendrik de Boer and Cornelis Zwikker[24] but not pursued. This was due to criticism in the former case by Albert Einstein and in the latter case by Brunauer. This flat surface equation may be used as a "standard curve" in the normal tradition of comparison curves, with the exception that the porous sample's early portion of the plot of versus acts as a self-standard. Ultramicroporous, microporous and mesoporous conditions may be analyzed using this technique. Typical standard deviations for full isotherm fits including porous samples are less than 2%.

Notice that in this description of physical adsorption, the entropy of adsorption is consistent with the Dubinin thermodynamic criterion, that is the entropy of adsorption from the liquid state to the adsorbed state is approximately zero.

Adsorbents

editCharacteristics and general requirements

editAdsorbents are used usually in the form of spherical pellets, rods, moldings, or monoliths with a hydrodynamic radius between 0.25 and 5 mm. They must have high abrasion resistance, high thermal stability and small pore diameters, which results in higher exposed surface area and hence high capacity for adsorption. The adsorbents must also have a distinct pore structure that enables fast transport of the gaseous vapors.[25] Most industrial adsorbents fall into one of three classes:

- Oxygen-containing compounds – Are typically hydrophilic and polar, including materials such as silica gel, limestone (calcium carbonate)[26] and zeolites.

- Carbon-based compounds – Are typically hydrophobic and non-polar, including materials such as activated carbon and graphite.

- Polymer-based compounds – Are polar or non-polar, depending on the functional groups in the polymer matrix.

Silica gel

editSilica gel is a chemically inert, non-toxic, polar and dimensionally stable (< 400 °C or 750 °F) amorphous form of SiO2. It is prepared by the reaction between sodium silicate and acetic acid, which is followed by a series of after-treatment processes such as aging, pickling, etc. These after-treatment methods results in various pore size distributions.

Silica is used for drying of process air (e.g. oxygen, natural gas) and adsorption of heavy (polar) hydrocarbons from natural gas.

Zeolites

editZeolites are natural or synthetic crystalline aluminosilicates, which have a repeating pore network and release water at high temperature. Zeolites are polar in nature.

They are manufactured by hydrothermal synthesis of sodium aluminosilicate or another silica source in an autoclave followed by ion exchange with certain cations (Na+, Li+, Ca2+, K+, NH4+). The channel diameter of zeolite cages usually ranges from 2 to 9 Å. The ion exchange process is followed by drying of the crystals, which can be pelletized with a binder to form macroporous pellets.

Zeolites are applied in drying of process air, CO2 removal from natural gas, CO removal from reforming gas, air separation, catalytic cracking, and catalytic synthesis and reforming.

Non-polar (siliceous) zeolites are synthesized from aluminum-free silica sources or by dealumination of aluminum-containing zeolites. The dealumination process is done by treating the zeolite with steam at elevated temperatures, typically greater than 500 °C (930 °F). This high temperature heat treatment breaks the aluminum-oxygen bonds and the aluminum atom is expelled from the zeolite framework.

Activated carbon

editThe term "adsorption" itself was coined by Heinrich Kayser in 1881 in the context of uptake of gases by carbons.[27]

Activated carbon is a highly porous, amorphous solid consisting of microcrystallites with a graphite lattice, usually prepared in small pellets or a powder. It is non-polar and cheap. One of its main drawbacks is that it reacts with oxygen at moderate temperatures (over 300 °C).

Activated carbon can be manufactured from carbonaceous material, including coal (bituminous, subbituminous, and lignite), peat, wood, or nutshells (e.g., coconut). The manufacturing process consists of two phases, carbonization and activation.[28][29] The carbonization process includes drying and then heating to separate by-products, including tars and other hydrocarbons from the raw material, as well as to drive off any gases generated. The process is completed by heating the material over 400 °C (750 °F) in an oxygen-free atmosphere that cannot support combustion. The carbonized particles are then "activated" by exposing them to an oxidizing agent, usually steam or carbon dioxide at high temperature. This agent burns off the pore blocking structures created during the carbonization phase and so, they develop a porous, three-dimensional graphite lattice structure. The size of the pores developed during activation is a function of the time that they spend in this stage. Longer exposure times result in larger pore sizes. The most popular aqueous phase carbons are bituminous based because of their hardness, abrasion resistance, pore size distribution, and low cost, but their effectiveness needs to be tested in each application to determine the optimal product.

Activated carbon is used for adsorption of organic substances[30] and non-polar adsorbates and it is also usually used for waste gas (and waste water) treatment. It is the most widely used adsorbent since most of its chemical (e.g. surface groups) and physical properties (e.g. pore size distribution and surface area) can be tuned according to what is needed.[31] Its usefulness also derives from its large micropore (and sometimes mesopore) volume and the resulting high surface area. Recent research works reported activated carbon as an effective agent to adsorb cationic species of toxic metals from multi-pollutant systems and also proposed possible adsorption mechanisms with supporting evidences.[32]

Water adsorption

editThe adsorption of water at surfaces is of broad importance in chemical engineering, materials science and catalysis. Also termed surface hydration, the presence of physically or chemically adsorbed water at the surfaces of solids plays an important role in governing interface properties, chemical reaction pathways and catalytic performance in a wide range of systems. In the case of physically adsorbed water, surface hydration can be eliminated simply through drying at conditions of temperature and pressure allowing full vaporization of water. For chemically adsorbed water, hydration may be in the form of either dissociative adsorption, where H2O molecules are dissociated into surface adsorbed -H and -OH, or molecular adsorption (associative adsorption) where individual water molecules remain intact [33]

Adsorption solar heating and storage

editThe low cost ($200/ton) and high cycle rate (2,000 ×) of synthetic zeolites such as Linde 13X with water adsorbate has garnered much academic and commercial interest recently for use for thermal energy storage (TES), specifically of low-grade solar and waste heat. Several pilot projects have been funded in the EU from 2000 to the present (2020).[citation needed] The basic concept is to store solar thermal energy as chemical latent energy in the zeolite. Typically, hot dry air from flat plate solar collectors is made to flow through a bed of zeolite such that any water adsorbate present is driven off. Storage can be diurnal, weekly, monthly, or even seasonal depending on the volume of the zeolite and the area of the solar thermal panels. When heat is called for during the night, or sunless hours, or winter, humidified air flows through the zeolite. As the humidity is adsorbed by the zeolite, heat is released to the air and subsequently to the building space. This form of TES, with specific use of zeolites, was first taught by John Guerra in 1978.[34]

Carbon capture and storage

editTypical adsorbents proposed for carbon capture and storage are zeolites and MOFs.[35] The customization of adsorbents makes them a potentially attractive alternative to absorption. Because adsorbents can be regenerated by temperature or pressure swing, this step can be less energy intensive than absorption regeneration methods.[36] Major problems that are present with adsorption cost in carbon capture are: regenerating the adsorbent, mass ratio, solvent/MOF, cost of adsorbent, production of the adsorbent, lifetime of adsorbent.[37]

In sorption enhanced water gas shift (SEWGS) technology a pre-combustion carbon capture process, based on solid adsorption, is combined with the water gas shift reaction (WGS) in order to produce a high pressure hydrogen stream.[38] The CO2 stream produced can be stored or used for other industrial processes.[39]

Protein and surfactant adsorption

editProtein adsorption is a process that has a fundamental role in the field of biomaterials. Indeed, biomaterial surfaces in contact with biological media, such as blood or serum, are immediately coated by proteins. Therefore, living cells do not interact directly with the biomaterial surface, but with the adsorbed proteins layer. This protein layer mediates the interaction between biomaterials and cells, translating biomaterial physical and chemical properties into a "biological language".[40] In fact, cell membrane receptors bind to protein layer bioactive sites and these receptor-protein binding events are transduced, through the cell membrane, in a manner that stimulates specific intracellular processes that then determine cell adhesion, shape, growth and differentiation. Protein adsorption is influenced by many surface properties such as surface wettability, surface chemical composition [41] and surface nanometre-scale morphology.[42] Surfactant adsorption is a similar phenomenon, but utilising surfactant molecules in the place of proteins.[43]

Adsorption chillers

editCombining an adsorbent with a refrigerant, adsorption chillers use heat to provide a cooling effect. This heat, in the form of hot water, may come from any number of industrial sources including waste heat from industrial processes, prime heat from solar thermal installations or from the exhaust or water jacket heat of a piston engine or turbine.

Although there are similarities between adsorption chillers and absorption refrigeration, the former is based on the interaction between gases and solids. The adsorption chamber of the chiller is filled with a solid material (for example zeolite, silica gel, alumina, active carbon or certain types of metal salts), which in its neutral state has adsorbed the refrigerant. When heated, the solid desorbs (releases) refrigerant vapour, which subsequently is cooled and liquefied. This liquid refrigerant then provides a cooling effect at the evaporator from its enthalpy of vaporization. In the final stage the refrigerant vapour is (re)adsorbed into the solid.[44] As an adsorption chiller requires no compressor, it is relatively quiet.

Portal site mediated adsorption

editPortal site mediated adsorption is a model for site-selective activated gas adsorption in metallic catalytic systems that contain a variety of different adsorption sites. In such systems, low-coordination "edge and corner" defect-like sites can exhibit significantly lower adsorption enthalpies than high-coordination (basal plane) sites. As a result, these sites can serve as "portals" for very rapid adsorption to the rest of the surface. The phenomenon relies on the common "spillover" effect (described below), where certain adsorbed species exhibit high mobility on some surfaces. The model explains seemingly inconsistent observations of gas adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics in catalytic systems where surfaces can exist in a range of coordination structures, and it has been successfully applied to bimetallic catalytic systems where synergistic activity is observed.

In contrast to pure spillover, portal site adsorption refers to surface diffusion to adjacent adsorption sites, not to non-adsorptive support surfaces.

The model appears to have been first proposed for carbon monoxide on silica-supported platinum by Brandt et al. (1993).[45] A similar, but independent model was developed by King and co-workers[46][47][48] to describe hydrogen adsorption on silica-supported alkali promoted ruthenium, silver-ruthenium and copper-ruthenium bimetallic catalysts. The same group applied the model to CO hydrogenation (Fischer–Tropsch synthesis).[49] Zupanc et al. (2002) subsequently confirmed the same model for hydrogen adsorption on magnesia-supported caesium-ruthenium bimetallic catalysts.[50] Trens et al. (2009) have similarly described CO surface diffusion on carbon-supported Pt particles of varying morphology.[51]

Adsorption spillover

editIn the case catalytic or adsorbent systems where a metal species is dispersed upon a support (or carrier) material (often quasi-inert oxides, such as alumina or silica), it is possible for an adsorptive species to indirectly adsorb to the support surface under conditions where such adsorption is thermodynamically unfavorable. The presence of the metal serves as a lower-energy pathway for gaseous species to first adsorb to the metal and then diffuse on the support surface. This is possible because the adsorbed species attains a lower energy state once it has adsorbed to the metal, thus lowering the activation barrier between the gas phase species and the support-adsorbed species.

Hydrogen spillover is the most common example of an adsorptive spillover. In the case of hydrogen, adsorption is most often accompanied with dissociation of molecular hydrogen (H2) to atomic hydrogen (H), followed by spillover of the hydrogen atoms present.

The spillover effect has been used to explain many observations in heterogeneous catalysis and adsorption.[52]

Polymer adsorption

editAdsorption of molecules onto polymer surfaces is central to a number of applications, including development of non-stick coatings and in various biomedical devices. Polymers may also be adsorbed to surfaces through polyelectrolyte adsorption.

In viruses

editAdsorption is the first step in the viral life cycle. The next steps are penetration, uncoating, synthesis (transcription if needed, and translation), and release. The virus replication cycle, in this respect, is similar for all types of viruses. Factors such as transcription may or may not be needed if the virus is able to integrate its genomic information in the cell's nucleus, or if the virus can replicate itself directly within the cell's cytoplasm.

In popular culture

editThe game of Tetris is a puzzle game in which blocks of 4 are adsorbed onto a surface during game play. Scientists have used Tetris blocks "as a proxy for molecules with a complex shape" and their "adsorption on a flat surface" for studying the thermodynamics of nanoparticles.[53][54]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Guruge, Amila Ruwan (2021-02-17). "Absorption Vs Adsorption". Chemical and Process Engineering. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ "Glossary". The Brownfields and Land Revitalization Technology Support Center. Archived from the original on 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ "absorption (chemistry)". Memidex (WordNet) Dictionary/Thesaurus. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ^ Atkins, P. W.; De Paula, Julio; Keeler, James (2018). Atkins' Physical chemistry (Eleventh ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-0-19-876986-6. OCLC 1020028162.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed] - ^ "adsorption". Gold Book. IUPAC. 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00155. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Ferrari, L.; Kaufmann, J.; Winnefeld, F.; Plank, J. (2010). "Interaction of cement model systems with superplasticizers investigated by atomic force microscopy, zeta potential, and adsorption measurements". J. Colloid Interface Sci. 347 (1): 15–24. Bibcode:2010JCIS..347...15F. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.03.005. PMID 20356605.

- ^ Khosrowshahi, Mobin Safarzadeh; Abdol, Mohammad Ali; Mashhadimoslem, Hossein; Khakpour, Elnaz; Emrooz, Hosein Banna Motejadded; Sadeghzadeh, Sadegh; Ghaemi, Ahad (26 May 2022). "The role of surface chemistry on CO2 adsorption in biomass-derived porous carbons by experimental results and molecular dynamics simulations". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 8917. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.8917K. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12596-5. PMC 9135713. PMID 35618757. S2CID 249096513.

- ^ Carroll, Gregory T.; Jongejan, Mahthild G. M.; Pijper, Dirk; Feringa, Ben L. (2010). "Spontaneous generation and patterning of chiral polymeric surface toroids". Chemical Science. 1 (4): 469. doi:10.1039/c0sc00159g. ISSN 2041-6520. S2CID 96957407.

- ^ Czelej, K.; Cwieka, K.; Kurzydlowski, K.J. (May 2016). "CO2 stability on the Ni low-index surfaces: Van der Waals corrected DFT analysis". Catalysis Communications. 80 (5): 33–38. doi:10.1016/j.catcom.2016.03.017.

- ^ Czelej, K.; Cwieka, K.; Colmenares, J.C.; Kurzydlowski, K.J. (2016). "Insight on the Interaction of Methanol-Selective Oxidation Intermediates with Au- or/and Pd-Containing Monometallic and Bimetallic Core@Shell Catalysts". Langmuir. 32 (30): 7493–7502. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01906. PMID 27373791.

- ^ Kayser, Heinrich (1881). "Über die Verdichtung von Gasen an Oberflächen in ihrer Abhängigkeit von Druck und Temperatur". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 248 (4): 526–537. Bibcode:1881AnP...248..526K. doi:10.1002/andp.18812480404.. In this study of the adsorption of gases by charcoal, the first use of the word "adsorption" appears on page 527: "Schon Saussure kannte die beiden für die Grösse der Adsorption massgebenden Factoren, den Druck und die Temperatur, da er Erniedrigung des Druckes oder Erhöhung der Temperatur zur Befreiung der porösen Körper von Gasen benutzte." ("Saussaure already knew the two factors that determine the quantity of adsorption – [namely,] the pressure and temperature – since he used the lowering of the pressure or the raising of the temperature to free the porous substances of gases.")

- ^ Foo, K. Y.; Hameed, B. H. (2010). "Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems". Chemical Engineering Journal. 156 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.013. ISSN 1385-8947. S2CID 11760738.

- ^ Czepirski, L.; Balys, M. R.; Komorowska-Czepirska, E. (2000). "Some generalization of Langmuir adsorption isotherm". Internet Journal of Chemistry. 3 (14). ISSN 1099-8292. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ^ a b Burke GM, Wurster DE, Buraphacheep V, Berg MJ, Veng-Pedersen P, Schottelius DD. Model selection for the adsorption of phenobarbital by activated charcoal. Pharm Res. 1991;8(2):228‐231. doi:10.1023/a:1015800322286

- ^ Physical Chemistry of Surfaces. Arthur W. Adamson. Interscience (Wiley), New York 6th ed

- ^ Kisliuk, P. (January 1957). "The sticking probabilities of gases chemisorbed on the surfaces of solids". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 3 (1–2): 95–101. Bibcode:1957JPCS....3...95K. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(57)90054-9.

- ^ Langmuir, I.; Schaefer, V.J. (1937). "The Effect of Dissolved Salts on Insoluble Monolayers". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 29 (11): 2400–2414. doi:10.1021/ja01290a091.

- ^ a b Chen, Jixin (2020). "Stochastic Adsorption of Diluted Solute Molecules at Interfaces". ChemRxiv. doi:10.26434/chemrxiv.12402404. S2CID 242860958.

- ^ Ward, A.F.H.; Tordai, L. (1946). "Time-dependence of Boundary Tensions of Solutions I. The Role of Diffusion in Time-effects". Journal of Chemical Physics. 14 (7): 453–461. Bibcode:1946JChPh..14..453W. doi:10.1063/1.1724167.

- ^ Condon, James (2020). Surface Area and Porosity Determinations by Physisorption, Measurement, Classical Theory and Quantum Theory, 2nd edition. Amsterdam.NL: Elsevier. pp. Chapters 3, 4 and 5. ISBN 978-0-12-818785-2.

- ^ Polanyi, M. (1914). "Über die Adsorption vom Standpunkt des dritten Wärmesatzes". Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft (in German). 16: 1012.

- ^ Polanyi, M. (1920). "Neueres über Adsorption und Ursache der Adsorptionskräfte". Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie. 26: 370–374.

- ^ Polanyi, M. (1929). "Grundlagen der Potentialtheorie der Adsorption". Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie (in German). 35: 431–432.

- ^ deBoer, J.H.; Zwikker, C. (1929). "Adsorption als Folge von Polarisation". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie (in German). B3: 407–420.

- ^ Yi, Honghong (April 2015). "Effect of the Adsorbent Pore Structure on the Separation of Carbon Dioxide and Methane Gas Mixtures". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 60 (5): 1388–1395. doi:10.1021/je501109q. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Viswambari Devi, R; Nair, Vijay V; Sathyamoorthy, P; Doble, Mukesh (2022). "Mixture of CaCO3 Polymorphs Serves as Best Adsorbent of Heavy Metals in Quadruple System". Journal of Hazardous, Toxic & Radioactive Waste. 26 (1). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)HZ.2153-5515.0000651. S2CID 240454883.

- ^ https://application.wiley-vch.de/books/sample/3527324712_c01.pdf

- ^ Spessato, L. et al. KOH-super activated carbon from biomass waste: Insights into the paracetamol adsorption mechanism and thermal regeneration cycles. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 371, Pages 499-505, 2019.

- ^ Spessato, L. et al. Optimization of Sibipiruna activated carbon preparation by simplex-centroid mixture design for simultaneous adsorption of rhodamine B and metformin. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 411, Page 125166, 2021.

- ^ Malhotra, Milan; Suresh, Sumathi; Garg, Anurag (2018). "Tea waste derived activated carbon for the adsorption of sodium diclofenac from wastewater: adsorbent characteristics, adsorption isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 25 (32): 32210–32220. Bibcode:2018ESPR...2532210M. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-3148-y. PMID 30221322. S2CID 52280860.

- ^ Blankenship, L. Scott; Mokaya, Robert (2022-02-21). "Modulating the porosity of carbons for improved adsorption of hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane: a review". Materials Advances. 3 (4): 1905–1930. doi:10.1039/D1MA00911G. ISSN 2633-5409. S2CID 245927099.

- ^ Mohan, S; Nair, Vijay V (2020). "Comparative study of separation of heavy metals from leachate using activated carbon and fuel ash". Journal of Hazardous, Toxic & Radioactive Waste. 24 (4): 473–491. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)HZ.2153-5515.0000520. PMID 04020031. S2CID 219747988.

- ^ Assadi, M. Hussein N.; Hanaor, Dorian A H (June 2016). "The effects of copper doping on photocatalytic activity at (101) planes of anatase TiO2: A theoretical study". Applied Surface Science. 387 (387): 682–689. arXiv:1811.09157. Bibcode:2016ApSS..387..682A. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.06.178. S2CID 99834042.

- ^ U.S. Pat. No. 4,269,170, "Adsorption solar heating and storage"; Inventor: John M. Guerra; Granted May 26, 1981

- ^ Berend, Smit; Reimer, Jeffery A; Oldenburg, Curtis M; Bourg, Ian C (2014). Introduction to carbon capture and sequestration. Imperial College Press. ISBN 9781306496834.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Deanna M.; Smit, Berend; Long, Jeffrey R. (16 August 2010). "Carbon Dioxide Capture: Prospects for New Materials". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 49 (35): 6058–6082. doi:10.1002/anie.201000431. PMID 20652916.

- ^ Sathre, Roger; Masanet, Eric (2013-03-18). "Prospective life-cycle modeling of a carbon capture and storage system using metal–organic frameworks for CO2 capture". RSC Advances. 3 (15): 4964. Bibcode:2013RSCAd...3.4964S. doi:10.1039/C3RA40265G. ISSN 2046-2069.

- ^ Jansen, Daniel; van Selow, Edward; Cobden, Paul; Manzolini, Giampaolo; Macchi, Ennio; Gazzani, Matteo; Blom, Richard; Henriksen, Partow Pakdel; Beavis, Rich; Wright, Andrew (2013). "SEWGS Technology is Now Ready for Scale-up!". Energy Procedia. 37: 2265–2273. Bibcode:2013EnPro..37.2265J. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.107.

- ^ (Eric) van Dijk, H. A. J.; Cobden, Paul D.; Lukashuk, Liliana; de Water, Leon van; Lundqvist, Magnus; Manzolini, Giampaolo; Cormos, Calin-Cristian; van Dijk, Camiel; Mancuso, Luca; Johns, Jeremy; Bellqvist, David (1 October 2018). "STEPWISE Project: Sorption-Enhanced Water-Gas Shift Technology to Reduce Carbon Footprint in the Iron and Steel Industry". Johnson Matthey Technology Review. 62 (4): 395–402. doi:10.1595/205651318X15268923666410. hdl:11311/1079169. S2CID 139928989.

- ^ Wilson, CJ; Clegg, RE; Leavesley, DI; Pearcy, MJ (2005). "Mediation of Biomaterial-Cell Interactions by Adsorbed Proteins: A Review". Tissue Engineering. 11 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1089/ten.2005.11.1. PMID 15738657. S2CID 19306269.

- ^ Sivaraman B.; Fears K.P.; Latour R.A. (2009). "Investigation of the effects of surface chemistry and solution concentration on the conformation of adsorbed proteins using an improved circular dichroism method". Langmuir. 25 (5): 3050–6. doi:10.1021/la8036814. PMC 2891683. PMID 19437712.

- ^ Scopelliti, Pasquale Emanuele; Borgonovo, Antonio; Indrieri, Marco; Giorgetti, Luca; Bongiorno, Gero; Carbone, Roberta; Podestà, Alessandro; Milani, Paolo (2010). Zhang, Shuguang (ed.). "The effect of surface nanometre-scale morphology on protein adsorption". PLoS ONE. 5 (7): e11862. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511862S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011862. PMC 2912332. PMID 20686681.

- ^ Cheraghian, Goshtasp (2017). "Evaluation of Clay and Fumed Silica Nanoparticles on Adsorption of Surfactant Polymer during Enhanced Oil Recovery". Journal of the Japan Petroleum Institute. 60 (2): 85–94. doi:10.1627/jpi.60.85.

- ^ Pilatowsky, I.; Romero, R.J.; Isaza, C.A.; Gamboa, S.A.; Sebastian, P.J.; Rivera, W. (2011). "Sorption Refrigeration Systems". Cogeneration Fuel Cell-Sorption Air Conditioning Systems. Green Energy and Technology. Springer. pp. 99, 100. doi:10.1007/978-1-84996-028-1_5. ISBN 978-1-84996-027-4.

- ^ Brandt, Robert K.; Hughes, M.R.; Bourget, L.P.; Truszkowska, K.; Greenler, Robert G. (April 1993). "The interpretation of CO adsorbed on Pt/SiO2 of two different particle-size distributions". Surface Science. 286 (1–2): 15–25. Bibcode:1993SurSc.286...15B. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(93)90552-U.

- ^ Uner, D.O.; Savargoankar, N.; Pruski, M.; King, T.S. (1997). "The effects of alkali promoters on the dynamics of hydrogen chemisorption and syngas reaction kinetics on Ru/SiO2 surfaces". Dynamics of Surfaces and Reaction Kinetics in Heterogeneous Catalysis, Proceedings of the International Symposium. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis. Vol. 109. pp. 315–324. doi:10.1016/s0167-2991(97)80418-1. ISBN 9780444826091.

- ^ Narayan, R.L; King, T.S (March 1998). "Hydrogen adsorption states on silica-supported Ru–Ag and Ru–Cu bimetallic catalysts investigated via microcalorimetry". Thermochimica Acta. 312 (1–2): 105–114. doi:10.1016/S0040-6031(97)00444-9.

- ^ VanderWiel, David P.; Pruski, Marek; King, Terry S. (November 1999). "A Kinetic Study on the Adsorption and Reaction of Hydrogen over Silica-Supported Ruthenium and Silver–Ruthenium Catalysts during the Hydrogenation of Carbon Monoxide". Journal of Catalysis. 188 (1): 186–202. doi:10.1006/jcat.1999.2646.

- ^ Uner, D. O. (1 June 1998). "A Sensible Mechanism of Alkali Promotion in Fischer−Tropsch Synthesis: Adsorbate Mobilities". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 37 (6): 2239–2245. doi:10.1021/ie970696d.

- ^ Zupanc, C.; Hornung, A.; Hinrichsen, O.; Muhler, M. (July 2002). "The Interaction of Hydrogen with Ru/MgO Catalysts". Journal of Catalysis. 209 (2): 501–514. doi:10.1006/jcat.2002.3647.

- ^ Trens, Philippe; Durand, Robert; Coq, Bernard; Coutanceau, Christophe; Rousseau, Séverine; Lamy, Claude (November 2009). "Poisoning of Pt/C catalysts by CO and its consequences over the kinetics of hydrogen chemisorption". Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 92 (3–4): 280–284. Bibcode:2009AppCB..92..280T. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.08.004.

- ^ Rozanov, Valerii V; Krylov, Oleg V (28 February 1997). "Hydrogen spillover in heterogeneous catalysis". Russian Chemical Reviews. 66 (2): 107–119. Bibcode:1997RuCRv..66..107R. doi:10.1070/rc1997v066n02abeh000308. S2CID 250890123.

- ^ Ford, Matt (6 May 2009). "The thermodynamics of Tetris". Ars Technica.

- ^ Barnes, Brian C.; Siderius, Daniel W.; Gelb, Lev D. (2009). "Structure, Thermodynamics, and Solubility in Tetromino Fluids". Langmuir. 25 (12): 6702–16. doi:10.1021/la900196b. PMID 19397254.

Further reading

edit- Cussler, E. L. (1997). Diffusion: Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 308–330. ISBN 978-0-521-45078-2.

External links

edit- Derivation of Langmuir and BET isotherms, at JHU.edu

- Carbon Adsorption, at MEGTEC.com