Ljuba Prenner (19 June 1906 – 15 September 1977) was a Slovene lawyer and writer, active in the interwar period. Prenner was assigned female at birth, but from a young age identified as male and began to transition to a male appearance as a teenager.[Notes 1] Prenner's family were not well-off and moved often in his childhood, before settling in Slovenj Gradec. Because of a lack of funds, Prenner often worked and had to change schools. Despite these difficulties, he graduated from high school in 1930 and immediately entered law school at the University of King Alexander I. He began publishing about this time and earned a living by tutoring other students and selling his writing. He published several short stories and novels including the first Slovenian detective story.

Ljuba Prenner | |

|---|---|

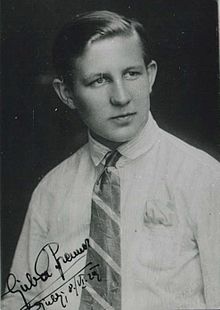

Prenner in 1929 | |

| Born | Amalia Marija Uršula Prenner 19 June 1906 Fara, Carinthia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 15 September 1977 (aged 71) Ljubljana, Socialist Republic of Slovenia, Yugoslavia |

| Nationality | Slovenian |

| Occupation(s) | lawyer, writer |

| Years active | 1936–1975 |

Completing a doctorate in 1941, Prenner opened a law practice and earned a reputation for defending political prisoners and those accused of crimes against the state. Now living as a male, his combative manner in the courtroom and strong sense of judicial independence led to his being imprisoned several times by the communist regime. After being expelled from the Slovene Writers' Association, he was unable to publish until shortly before his death. Prenner was released from prison in 1950 and began a campaign to have his law license restored. From 1954, he was allowed to practice again and was known for rarely losing a case. He was asked in 1968 to give the speech for the Bar Association's centennial celebrations and in 1970 was appointed as the permanent German-language court interpreter for Slovenia.

Prenner died from breast cancer in 1977. Changes in social conventions and celebrations for the hundredth anniversary of his birth have led to a re-examination of his life in biographies and documentaries, as well as publication of some of his previously unpublished autobiographical novels.

Early life and education (1906–1930)

editLjuba Prenner was born Amalia Marija Ursula Prenner on 19 June 1906, in Fara, near Prevalje, in the Slovene province of Carinthia, Austria-Hungary, to Marija Čerče and Josef Prenner.[3][9][10] His father was a German carpenter and gunsmith from Kočevje. His mother was a Slovene, the daughter of a winemaker and cobbler. Though his father was not fluent in Slovene and his mother spoke no German, Prenner spoke both those languages from a young age.[3] He discarded his baptismal name and adopted the name Ljuba, a name with varied forms used for both males and females in various Slavic languages, as soon as he recognized his ability to think independently.[10] He had a younger sister, Josipina, and an older half-brother, Ivan Čerče, an illegitimate child conceived before his mother married.[3][11]

Prenner's family was not well-off and moved often because of the father's work. He has completed first grade in Ruše, where the family moved in 1910, and the next three grades in Slovenj Gradec.[3][12] Education was barred to most women at the time, as traditional Christian values required that they be subordinate and confined to the domestic sphere.[5][13] High schools did not admit girls and a university education was required a secondary education diploma.[5] At the end of World War I, Slovenia became part of the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[14] Women created organizations and demanded equality in the new country, including the right to vote, earn a living, and access to education.[15] It was not until 1929 that coeducational compulsory education for eight grades was enacted in the country, which in that year, became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[16] 1929 was also the first year that women were allowed to participate in the legal profession in Slovenia.[17]

In 1919, Prenner enrolled in the private Ptuj State Gymnasium and was able to finish three years before a lack of funds forced him to return home. He studied his fourth year courses privately in Celje and then returned to Ptuj to take the examination to certify completion of the grade.[3][18] As a teenager, Prenner began to cut his hair short and began transitioning his appearance from female to male.[5] He also began attending theater events and literary evenings that exposed him to Slovenian culture and instilled a desire to continue his education. Short of funds, he took a position as a typist in a law firm in Slovenj Gradec, increasing his savings for the next two years. He then moved to Belgrade and enrolled in the First Women's Realgymnasium. He completed his fifth and sixth years of high school there while working as a hospital attendant and a clerk for a plumbing company. After exhausting his savings he returned home and completed the remaining two years of high school through private study.[3][19] In 1930, he successfully passed the Matura matriculation at the Ljubljana Lyceum,[20] having proven proficiency in English, French, German, and Italian.[21]

University studies and early literary career (1929–1939)

editPrenner immediately enrolled in law school at the University of King Alexander I.[20] Though he tutored many of his colleagues, he failed almost every examination at the first attempt, whereas those he taught passed.[5] It took him six years to earn his law degree because of the discriminatory practices he encountered and his need to work.[5][20] In addition to tutoring, he published short stories to earn money.[20] Between 1936 and 1937, he completed his legal internship with Josip Lavrič in Slovenj Gradec and then moved to Ljubljana to facilitate studying for a doctorate.[3][22]

Despite studying to become a lawyer, Prenner hoped to become a writer. His short stories like Trojica (1929) and Življenje za hrbtom (1936), and novels such as Pohorska vigred v časopisu Jutro (1930–31) and Mejniki ali kronika malega sveta v reviji Ženski svet (1936–38), eschewed the prevailing Socialist realism model then popular for literary works. Rather than an ideologically driven text, Prenner's works were characterized by the human ability to adapt to life with faith, humor, and irony.[5] He wrote many situational comedies using satire and wit.[23] Almost all these works are set in a small town, feature a lawyer, and contain autobiographical elements[24] with a typically male protagonist.[6] These literary efforts judged as light entertainments rather than serious literary efforts. As a result, most of his works were never published. In 1939, he published the first crime novel in Slovenia, Neznani storilec (The Unknown Perpetrator).[5] That year, he was admitted to membership in the Slovene Writers' Association.[10]

Prenner worked in two different law firms and completed his graduate studies in 1941.[22] That year, Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers of Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary, and Italy, who partitioned the country. Slovenia was split in half, with Italy taking the western portion and Germany taking the eastern part.[25] The following year, he passed his bar examination. The fact that he was born in what was now the German-controlled half of Slovenia would have prevented the Italian authorities from granting him a license to practice in their territory, which included Ljubljana.[26] Taking advantage of the fact that the name of his birthplace was not unique, Prenner applied for a license and gave Fara as his birthplace without specifying its location and the Italians assumed it was the Fara they controlled in Kočevje and issued him a license.[3][27]

Legal career, activism, and imprisonment (1939–1954)

editNow increasingly living as a male, during his doctorate studies Prenner joined the Osvobodilna fronta (Liberation Front, OF), an anti-fascist civil resistance movement. His apartment was used for meetings and as a dropbox for partisan communiques. He housed comrades who needed shelter for a night and provided legal advice or defense to detainees and prisoners.[27] As he refused to join the communist party on account of their methods rather than their ideology, party leaders began to watch him as a potential opponent.[3] Prenner opened a private law practice in 1943,[27] and gained a reputation for his work during the war with political prisoners. In one scheme, he filed false paperwork with the authorities claiming that the judgments of the Italian courts were invalid after Italy capitulated to the Allies. He secured the freedom of many Slovenes before the Germans realized their error and arrested him in 1944. He escaped imprisonment, but had to pay a large fine.[3][28]

When the war ended, Prenner was one of only 13 lawyers allowed to continue practicing by the communist government.[3][29] In 1946, he was assigned to represent the partisan Tončko Vidic, who had been sentenced to death for treason. Prenner thought that the conviction was based on flimsy evidence and found witnesses who were able to prove that the charges were false. He demanded a retrial, earning an acquittal for his client. In the aftermath of the trial, he and the prosecutor, whose weak case he had exposed, engaged in a physical altercation, which resulted in Prenner being fined by the disciplinary court.[3][30] He became known as a lawyer who rarely lost a case, using unyielding determination and legal acumen.[10] Among those he represented who were accused of collaborating with the Italian occupation authorities were Juro Adlešič, former mayor of Ljubljana; the owner of the cinema in Ljubljana; and Slovenes who had participated with Draža Mihailović in resistance during the war.[30]

Prenner represented those charged with crimes against the state or state property, refusing to represent clients he did not consider to be wrongly accused. He believed that the judiciary had to maintain its independence from the government and not be swayed by politics. This often led to confrontations with those who saw the courts as an enforcer for the communist regime.[3] In 1947, the communist newspaper, Slovenski poročevalec (The Slovene Reporter), published an article strongly criticizing Prenner. It alleged that he undermined the reputation and authority of prosecutors, the court system, the State Security Administration, and the government by inappropriately belittling the performance of officials.[3][30] He was arrested and spent a month and a half in a pre-trial jail located on Miklošičeva cesta (Miklosich Street). While in jail, he composed the libretto Slovo od mladosti (Farewell from Youth).[3]

Though Prenner's comedy Veliki mož (The Great Man) was successfully staged in 1943 at the Ljubljana Drama Theatre, in 1947 it was attacked by the literary censors and he was expelled from the Writers Association. He was not allowed to publish again until 1976.[10] Released from prison in the fall of 1947, he began working part-time at the Institute of the Slovene Language, part of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, advising on legal concepts for the Slovene language dictionary. He was arrested by the State Security Administration in 1949 and returned to the jail on Miklošičeva cesta.[3] Officially, he was never charged with an offense and kept his job until 1952. He was moved from the pre-trial jail to the Ferdreng Women's Camp and required to work in the quarry. To keep up his spirits and those of the other inmates, Prenner wrote the humorous piece, Prošnja za novo stranišče (Request for a New Toilet), stressing the inadequacy of three toilets for 300 prisoners. He helped the other prisoners by filing complaints about the poor food and sexual assaults, which often earned him time in solitary confinement.[3][31]

After a new complaint was made against Prenner later in 1949, he was transferred to the Ljubljana District Court Prison, but when the charges were withdrawn, he was sent to the women's prison at Brestanica castle. In January 1950, he was again transferred and imprisoned in the castle at Škofja Loka, where he wrote the play, Vasovalci. He was released without receiving either an indictment or a pardon in May 1950, but had no job to return to,[3][31] as his law license had been revoked.[28] Initially he lived in Rožna Dolina, with his long-term female partner, Slavica Jelenc, who was a mathematics professor.[32] When his brother-in-law Josip Šerbec died, Prenner moved to Bežigrad, where his sister lived. Unable to sell his writing, he took care of the family, helped his nephews who were law students, and worked as a clerk in a law office. Unable to earn enough money to support the family, he and his sister sold their parents' home in Slovenj Gradec, which they had inherited after their parents died in 1945.[3][31]

Later life (1954–1976)

editHaving been barred from working as a lawyer for seven years,[28] after a long letter-writing campaign to various officials and organizations, Prenner regained his license in 1954.[3][31] That year, he hoped to revive his literary career. His libretto Slovo od mladosti was staged by composer Danilo Švara at the Ljubljana Opera House. It received unenthusiastic reviews, closing the door on his literary ambitions. Prenner reopened a practice and hired his nephews, Vojmil and Smiljan Šerbec as interns. Once again he became a coveted advocate in the criminal court. Though highly skilled, Prenner's combative nature in court resulted in him being brought before the Bar Association's disciplinary commission several more times in the 1960s.[3][33] He also became popular with personalities who were considered controversial by the communist authorities, such as Lili Novy and Anton Vovk. Božidar Jakac painted several portraits of Prenner.[3]

Though he did not support the Yugoslav communist regime, Prenner acknowledged that after the communists took power, he was able to dress as he pleased.[28] Typically, he was attired in a man's suit, worn with a white shirt and tie, and he carried a briefcase. In public, he always used feminine language to refer to himself, but in private, his friends and family recognized him as a man.[5] With his literary works, Prenner was able to "come to life as a man".[34] He was pragmatic about the situation, and has been widely quoted as having introduced himself by saying, "I am Dr. Ljuba Prenner, neither man nor woman".[10][5] He also wrote a letter to a colleague explaining that his appearance made his life as a lawyer simpler; though he recognized that he was not a man, he was more comfortable having the freedom to be who he felt he was.[10]

Prenner made no efforts to hide his sexual orientation[6][12] and his father accepted his gender identity, though his mother did not approve.[35] In his childhood, Prenner met Štefka Vrhnjak, who would later become a teacher and headmistress in Sela, near Slovenj Gradec. Though he had other relationships, Vrhnjak was Prenner's great love and when she died in 1960,[5] Prenner met Marija Krenker at the funeral.[28] Krenker was Vrhnjak's niece and a widow[Notes 2] running an inn to support her four daughters.[10][37] The Bučinek family, which included the actress Jerica Mrzel, provided support for Prenner while he became a father figure for the girls.[28][38] In 1966, he moved to Šmiklavž and with encouragement from Krenker, began trying to write his memoirs. He wanted to retire, but the authorities claimed he had not worked the requisite years of service, since the years spent writing and in prison were not recognized.[23]

In 1967, Prenner's comedy, Gordijski vozel (Gordian Knot) aired on the Italian station Radio Trst A, but he was still unable to publish in Slovenia.[3] Based on his reputation, he was asked in 1968 to give the centenary speech for the bar celebrations. His presentation was Odvetnik v slovenski literaturi (The Lawyer in Slovenian Literature).[3][33] In 1970, he was appointed as the permanent German-language court interpreter for Slovenia,[39] but around that time began having health problems, including diabetes. He retired in 1975 and his nephew Vojmil took over the law office. In 1976, without his having sought acceptance, the Slovene Writers' Association readmitted him to membership and granted him a small pension based on his literary contributions from 1929.[3][23]

Death and legacy

editPrenner died on 15 September 1977 at the hospital on Zaloška Road in Ljubljana[3][9] from breast cancer.[5] He was buried alongside his parents at the cemetery in Stari Trg.[10] Prenner was recognized for many years as a woman who chose to assert her agency at a time when most women were not allowed to,[28] but was rarely recognized in Slovenia as a butch lesbian or transgender man.[40][41] A biography titled Odvetnica in pisateljica Ljuba Prenner (Lawyer and Writer Ljuba Prenner) published in 2000 "completely ignored [Prenner's] sexuality".[42] Camouflaging the sexual orientation of biographical subjects was common through the 20th century in Slovenia,[43] but in the 21st century more openness in society has allowed a more balanced presentation of Prenner's life, including Prenner's exploration of sex reassignment surgery and some studies call Prenner transgender.[44][45][46][Notes 3]

Prenner is remembered for an independent spirit, legal expertise, and written works.[28] In 2000, Prenner's biography was published by Nova Revija, drawing on interviews with acquaintances[5] and he was included in the 2007 publication Pozabljena polovica: portreti žensk 19. in 20. stoletja na Slovenskem (The Forgotten Half: Portraits of Women of the 19th and 20th Centuries in Slovenia). Other literary and scientific works have assessed Prenner's place in Slovenian history since the dissolution of Yugoslavia.[51] There is a memorial hall dedicated to Prenner's memory in the Carinthian Provincial Museum, which houses his papers and artifacts.[5] On the centennial of his birth, director Boris Jurjaševič premiered a documentary film biography: Dober človek: Ljuba Prenner (The Good Man: Ljuba Prenner).[37]

Mrzel, who is the literary guardian of Prenner's estate, has arranged for the publication of some of Prenner's previously unpublished works.[38] Bruc: roman neznanega slovenskega študenta (Freshman: The Novel of an Unknown Slovene Student) was published in 2006.[24][52] It focuses on the experiences of a young man striving to attain an education in the social environment of the interwar period. It explores gender roles and the limits that gender places on one's ability to engage in society, and it evidences Prenner's belief that sexual identity is fluid.[53][54] His memoirs, Moji spomini, begun in 1970, were published in 2007.[55]

As of 2024, an interactive display at the City Museum of Ljubljana included a photo of Prenner among a group of images of significant figures in Ljubljana's history, inviting visitors to guess their identities and rotate the images to read a biography on the reverse. The biography for Prenner was titled "The Female Attorney in Trousers" (Odvetnica v Hlačah) referred to "her dual-gender identity" and used feminine pronouns for its subject.

Selected works

edit- Prenner, Ljuba (1929). "Skok, Cmok in Jokica". Jutra (in Slovenian) (4). Ljubljana. OCLC 440348511. Fairy tale, written under the pseudonym Tetka Metka.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)[56] - Prenner, Ljuba (1929). Trojica (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Belo-modra knjižnica. OCLC 441720322.[56]

- Prenner, Ljuba (1931). "Pohorska vigred". Jutra (in Slovenian). Ljubljana. Serialized novel published between 1930 and 1931 in various issues.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)[56] - Prenner, Ljuba. "Mejniki ali Kronika malega mesta". Revija Ženski svet (in Slovenian). Trieste, Italy: Žensko dobrodelno udruženje. Serialized novel printed in various issues between 1936 and 1938.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)[56] - Prenner, Ljuba (1936). Življenje za hrbtom (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Evalit. OCLC 441710999.[56]

- Prenner, Ljuba (1939). Neznani storilec (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Vodnikova družba. OCLC 442569764.[56]

- Prenner, Ljuba (1943). Veliki mož (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Slovensko narodno gledališče. OCLC 883930495.[56]

- Prenner, Ljuba (1945). Vasovalci (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Samozaložba. OCLC 438941186.[57]

- Prenner, Ljuba (1967). Gordijski vozel (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Samozaložba. OCLC 441108789.[58]

- Prenner, Ljuba (1988). Slovo od mladosti (Prešeren) (in Slovenian) (2nd ed.). Ljubljana: Slovensko narodno gledališče. OCLC 456163334. Libretto for the opera ballet written in 1947, first staged by Danilo Švara in 1954 at the Ljubljana Opera House and restaged in 1988. The initial title was Prešeren, which was changed before it premiered to Slovo od mladosti.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)[59] - Prenner, Ljuba (2006). Makuc, Andrej; Rajšter, Brigita (foreword) (eds.). Bruc: roman neznanega slovenskega študenta (in Slovenian). Slovenj Gradec: Cerdonis. ISBN 978-961-6244-24-4.[52]

- Prenner, Ljuba (Winter 2007). "Moji spomini". Odsevanja (in Slovenian) (67–68). Slovenj Gradec: Kulturno društvo Odsevanja Slovenj Gradec: 21–32. ISSN 0351-3661. OCLC 439642154.

Notes

edit- ^ Most historic texts refer to Prenner as a woman and do not mention either sexuality or gender.[1][2] The majority of biographies consulted indicate Prenner publicly lived as a woman and used feminine language about himself in the public sphere, but in the courtroom, when writing, and in private, lived as a male.[3][4][5][6][7] Prenner had "an understanding of himself as a lesbian who used masculine identifiers and existed outside of the binary of male and female".[8]

- ^ Krenker was twice widowed. Once from her daughters' father, Bučinek, and later by their step-father.[36]

- ^ "Same-sex sexual acts in Slovenia were illegal until 1977". The first homosexual organization for men was developed in 1984 and for women in 1985. Legal protection of LGBT rights began in 1991.[47] Official state policy in Eastern Europe provided for equality of women, but segregated employment and social roles by gender in a binary hierarchy.[48] Beginning in the 1990s research on gender history during the Soviet period began by examining all areas of intimate and domestic life. Scholars of gender and sexual variance emerged in the post-socialist era to evaluate the inclusion of homosexuality in the 20th century in the region and to challenge public silence regarding their history.[49] The break-up of the USSR allowed scholars to begin evaluating the varied history of cultural sexuality in the states of Eastern Europe.[50]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Tratnik 2001, p. 375.

- ^ Greif 2014, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Dolgan, Fridl & Volk 2014, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, pp. 1, 88–89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Pirnar 2003.

- ^ a b c Ciglar 2011, p. 42.

- ^ Šelih 2007, pp. 436–437.

- ^ Darling 2018.

- ^ a b Lukman 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kotnik 2016.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 21.

- ^ a b Fabjančič 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 10.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 16.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 22.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d Fabjančič 2016, p. 23.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 87.

- ^ a b Fabjančič 2016, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Fabjančič 2016, p. 31.

- ^ a b Fabjančič 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Roberts 1973, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Rodogno 2006, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Fabjančič 2016, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smajila 2014.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Fabjančič 2016, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Fabjančič 2016, p. 29.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, pp. 29, 84.

- ^ a b Fabjančič 2016, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 82.

- ^ a b Fabjančič 2016, p. 38.

- ^ a b Fabjančič 2016, p. 78.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 30.

- ^ Petrović 2018, p. 160.

- ^ Tratnik 2001, pp. 375–376.

- ^ Greif 2014, p. 167.

- ^ Greif 2014, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Petrović 2018, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 81.

- ^ Tratnik 2007.

- ^ Plut-Pregelj et al. 2018, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Baker 2017a, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Baker 2017a, p. 5.

- ^ Baker 2017b, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 2.

- ^ a b Petrović 2018, p. 199.

- ^ Petrović 2018, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fabjančič 2016, p. 33.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 34.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Fabjančič 2016, pp. 34–35.

Bibliography

edit- Baker, Catherine (2017a). "Introduction: Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR". In Baker, Catherine (ed.). Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-137-52804-9.

- Baker, Catherine (2017b). "Transnational 'LGBT' Politics after the Cold War and Implications for Gender History". In Baker, Catherine (ed.). Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 228–251. ISBN 978-1-137-52804-9.

- Ciglar, Barbara Jarh (2011). "Lezbična ljubezen v sodobnem slovenskem romanu" [Lesbian Love in the Contemporary Slovene Novel] (PDF). Jezik in Slovstvo (in Slovenian). LVI (5–6). Ljubljana: Slavisticno Drustvo Slovenije: 39–56. ISSN 0021-6933. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Darling, Laura (Mills) (14 November 2018). "Ljuba Prenner". Making Queer History. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Dolgan, Marjan; Fridl, Jerneja; Volk, Manca (2014). "67. Ljuba Prenner [VIII]". Literarni atlas Ljubljane. Zgode in nezgode 94 slovenskih književnikov v Ljubljani [Literary Atlas of Ljubljana. The Incidents and Accidents of 94 Slovenian Writers in Ljubljana] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Založba ZRC. pp. 162–164. ISBN 978-961-254-711-0. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017.

- Fabjančič, Maša (2016). Prikaz študentskega življenja Ljube Prenner na podlagi romana Bruc: roman neznanega slovenskega študenta [Presentation of the Academic Life of Ljuba Prenner Based on the Novel Freshman: A Novel of an Unknown Slovene Student] (graduate thesis) (in Slovenian). Koper, Slovenia: University of Primorska.

- Greif, Tatjana (2014). "7. The Social Status of Lesbian Women in Slovenia in the 1990s". In Coleman, Edmond J.; Sandfort, Theo (eds.). Sexuality and Gender in Postcommunist Eastern Europe and Russia. New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 149–170. ISBN 978-1-317-95559-7.

- Kotnik, Mateja (21 June 2016). "Ljuba Prenner: "Hlače nosim, da lažje živim"" [Ljuba Prenner: "I wear pants to make life easier"]. Delo (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Lukman, Franc Ksaver, ed. (2013). "Prenner, Ljuba (1906–1977)". Slovenska biografija (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia: Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Petrović, Jelena (2018). Women's Authorship in Interwar Yugoslavia: The Politics of Love and Struggle. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-00142-1.

- Pirnar, Marta (25 September 2003). "Dr. Ljuba Prenner: pozabljena odvetnica" [Dr. Ljuba Prenner: A Forgotten Lawyer]. Cosmopolitan Slovenija (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia: Adria Media. ISSN 2350-5982. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Plut-Pregelj, Leopoldina; Kranjc, Gregor; Lazarević, Žarko; Rogel, Carole (2018). Historical Dictionary of Slovenia (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-1106-2.

- Roberts, Walter R. (1973). Tito, Mihailović, and the Allies, 1941–1945. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-0740-8.

- Rodogno, Davide (2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84515-1.

- Šelih, Alenka (2007). "Ljuba Prenner". Pozabljena polovica: portreti žensk 19. in 20. stoletja na Slovenskem [Forgotten Half: Portraits of 19th and 20th Century Women in Slovenia] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Zalozba Tuma. pp. 436–439. ISBN 978-961-6682-01-5.

- Smajila, Barbara (21 November 2014). "Ljuba Prenner: jeklena odvetnica, ki je pogumno nosila hlače" [Ljuba Prenner: A Steely Lawyer Who Bravely Wore Pants]. Dnevnik (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Tratnik, Suzana (26 July 2007). "Ko se je pojavila dr. Prennerjeva, se je spremenilo ozračje" [When Dr. Prenner Showed Up the Atmosphere Changed]. Narobe (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Društveno informacijski center Legebitra. ISSN 1854-8474. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Tratnik, Suzana (August 2001). "Lesbian Visibility in Slovenia". European Journal of Women's Studies. 8 (3). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publishing: 373–380. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1001.1430. doi:10.1177/135050680100800308. ISSN 1350-5068. S2CID 145284738.