This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2011) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

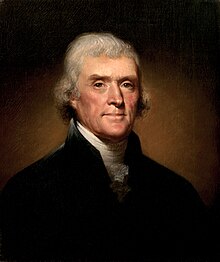

Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) was a book written by Thomas Jefferson who was also the author of the Declaration of Independence. He completed the first edition in 1781, and updated and enlarged the book in 1782 and 1783. Notes on the State of Virginia originated in Jefferson's responding to questions about Virginia, posed to him in 1780 by François Barbé-Marbois, then Secretary of the French delegation in Philadelphia, the temporary capital of the united colonies. Often dubbed the most important American book published before 1800, Notes on the State of Virginia is both a compilation of data by Jefferson about the state's natural resources and economy, and his vigorous and often eloquent argument about the nature of the good society, which he believed was incarnated by Virginia. He expressed his beliefs in the separation of church and state, constitutional government, checks and balances, and individual liberty. He wrote extensively about slavery, the problems of miscegenation, and his belief that whites and blacks could not live together in a free society.

It was the only full-length book which Jefferson published during his lifetime. He first published it anonymously in Paris in 1785 where he was serving the US government as trade representative. He published the book in its first English edition in 1787 in London.

Publication and contents edit

Notes was anonymously published in Paris in a limited, private edition of a few hundred copies in 1785 after it came to Jefferson’s attention that an unauthorized publishing had already occured.[1] Its first public English-language edition, issued by John Stockdale in London, appeared in 1787. It was the only full-length book by Jefferson published during his lifetime, though he did issue a Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States, generally known as Jefferson's Manual, in 1801 and published a re-write of the Gospel of Jesus in 1816 entitled: “The Morals and Life of Jesus of Nazareth”, removing the miracles and depicting Christ as just a mortal man teaching moral lessons (a project started in 1802 after charges of atheism were made against him.)[2]

Notes includes some of Jefferson's most memorable statements of belief in such political, legal, and constitutional principles as the separation of church and state, constitutional government, checks and balances, and individual liberty. He celebrated the resources of Virginia. Overall, Jefferson was arguing with the proposition of the French naturalist Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who in his authoritative Histoire Naturelle said that nature, plant life, animal life, and human life degenerate in the New World by contrast with their state in the Old World.[citation needed]

Outline edit

The text is divided into 23 chapters, which Jefferson termed "Queries," each describing a different aspect of the state of Virginia.

- Boundaries of Virginia

- Rivers

- Sea Ports

- Mountains

- Cascades

- Productions mineral, vegetable and animal

- Climate

- Population

- Military force

- Marine force

- Aborigines

- Counties and towns

- Constitution

- Laws

- Colleges, buildings, and roads

- Proceedings as to Tories

- Religion

- Manners

- Manufactures

- Subjects of commerce

- Weights, Measures and Money

- Public revenue and expenses

- Histories, memorials, and state-papers

Jefferson on Freedom of Speech and Secular Government edit

“Notes on the State of Virginia” contained Jefferson's firm belief in citizen's rights to express themselves freely without fear of government or church reprisal and that government’s role is only secular and should not have anything to do with religion.[3] This led later to charges of atheism leveled at him by his opponants in Federalist newspapers leading up to the nasty election of 1800. [4] They quoted his European published "Notes on Virginia" as proof that he was Godless.

Jefferson wrote in “Notes on Virginia”:

The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.[5]

Biographer Joseph J. Ellis reveals that Jefferson didn't think the work would be known in the US since he did not publish it in North America and kept his authorship anonymous in Europe. He exchanged letters with friends worried what they would think about his authorship of such a religious heresy. They supported him in response. Jefferson did not respond at all to the mud-slinging charges. He won the 1804 presidential election anyway, but those charges of atheism and the charges of an affair with his 15 year old slave Sally Hemmings published in newspapers by Federalists supporters put his belief in a free press and free speech to the test.

While his predecessor John Adams angrily counter-attacked the press and vocal opponents by passing chilling Alien and Sedition Acts (the equivalent of today's so-called "Patriot Act" and NDAA Acts), Jefferson, by contrast, worked tirelessly to overturn these tyrannical limits on free speech and free press, despite the great personal damage such open discourse did to his reputation. He later lamented the anguish caused by his political enemies, however, he never denied the charges made by them, including those in “Notes on Virginia”; and he never gave up his fight for “Republican priciples” to shield the common man from state or religious oppression (as opposed to the Aristocratical Federalists’ doctrine that he successfully ousted.) [6]

Jefferson and slavery edit

In "Laws" (Query XIV-14), Jefferson described the rise of slavery and justified it, by referring to what he called "the real distinctions which nature has made" between people of European descent and people of African descent. He later expressed his opposition to slavery in "Manners" (Query XVIII-18). In "Laws," Jefferson expressed contemporary beliefs among many Americans that Africans were inferior to Whites in terms of potential citizenship; as a result, he supported deporting them for colonization in Africa. Jefferson claimed his solution was related to the common good for both Whites and Blacks. He proposed a three-fold process of education, emancipation (after the age of 45, to repay the slaveholder's investment), and colonization of free blacks to locations in Africa. He endorsed this plan all his life but never took political action to make it happen.

Jefferson's proposal for resettling freed blacks in a colony in Africa expressed the mentality and anxieties of some American slaveholders after the American Revolutionary War; this contrasted with rising sentiment among other men to emancipate slaves based on ideals related to the colonies' struggle for independence. Numerous northern states abolished slavery all together. Several southern states, including Virginia in 1782, made manumissions easier. So many slaveholders in Virginia freed slaves following the Revolution (sometimes by will and others during their lifetime) that the number of free blacks in Virginia rose from about 1800 in 1782 to 30,466, or 7.2 percent of the black population in 1810.[7] In the Upper South, more than 10 percent of blacks were free by 1810; in northern states, more than three-quarters of blacks were free by that date.[8]

Jefferson wrote:

"It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race."

Some slave-owners feared race wars could ensue upon emancipation, due not least to natural retaliation by blacks for the injustices under long slavery. Jefferson may have thought his fears justified after the revolution in Haiti, marked by widespread violence in the mass uprising of slaves against white colonists and free people of color in their fight for independence. Thousands of white and free people of color came as refugees to the United States in the early 1800s; many brought their slaves with them. In addition, uprisings such as that of Gabriel in Richmond, Virginia, were often led by literate blacks. Jefferson and some other slaveholders embraced the idea of "colonization": arranging for transportation of free blacks to Africa, regardless of their being native-born and having lived in the United States. In 1816 the American Colonization Society was founded in a collaboration by abolitionists and slaveholders.

Jefferson said he thought Blacks were inferior to Whites in terms of beauty and reasoning intelligence.[9] In "Manners," Jefferson wrote that slavery was demoralizing to both White and Black society and that man is an "imitative animal."

Influence edit

Jefferson's work inspired others by his reflections on the nature of society, human rights and government. Some supporters of abolition considered his thoughts on blacks and slavery as an obstacle to achieving equal rights for free blacks in the United States (However, former first lady Abigail Adams, the most influential woman in America and a leading Abolitionist, was supportive.) People argued against Jefferson's ideas in the Notes long after he died. For instance, the abolitionist David Walker, a free black, opposed the colonization movement. In Article IV of his Appeal (1830), Walker said that free blacks considered colonization as the desire of whites to remove free blacks

"from among those of our brethren whom they unjustly hold in bondage, so that they may be enabled to keep them the more secure in ignorance and wretchedness, to support them and their children, and consequently they would have the more obedient slave. For if the free are allowed to stay among the slave, they will have intercourse together, and, of course, the free will learn the slaves bad habits, by teaching them that they are MEN, as well as other people, and certainly ought and must be FREE."

Jefferson's passages about slavery and the black race in Notes are referred to and disputed by Walker in the Appeal. Walker valued Jefferson as "one of as great characters as ever lived among the whites," but he opposed his ideas:

"Do you believe that the assertions of such a man, will pass away into oblivion unobserved by this people and the world?...I say, that unless we try to refute Mr. Jefferson's arguments respecting us, we will only establish them."[10]

He went on:

"Mr. Jefferson's very severe remarks on us have been so extensively argued upon by men whose attainments in literature, I shall never be able to reach, that I would not have meddled with it, were it not to solicit each of my brethren, who has the spirit of a man, to buy a copy of Mr. Jefferson's Notes on Virginia, and put it in the hand of his son. For let no one of us suppose that the refutations which have been written by our white friends are enough—they are whites—we are blacks. We, and the world wish to see the charges of Mr. Jefferson refuted by the blacks themselves, according to their chance; for we must remember that what the whites have written respecting this subject, is other men's labours, and did not emanate from the blacks."

References edit

- R. B. Bernstein, Thomas Jefferson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003; pbk, 2005) ISBN 978-0-19-518130-2

- Robert A. Ferguson, Law and Letters in American Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984) ISBN 978-0-674-51466-9

- Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993; pbk, 1994

- The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson. The Modern Library, 1944.

- Thomas Jefferson: Writings: Autobiography / Notes on the State of Virginia / Public and Private Papers / Addresses / Letters (1984, ISBN 978-0-940450-16-5) Library of America edition.

- David Tucker, Enlightened Republicanism: A Study of Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia (Lexington Books, 2008) ISBN 978-0-7391-1792-7

- David Walker, Appeal, 1830, electronic text, Documents of the American South, University of North Carolina

Notes edit

- ^ American Sphinx

- ^ Joseph J. Ellis. [xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx "American Sphinx, p. 309"].

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) “Primative Christianity, in his view, was similar to the original meaning of the American Revolution: a profoundly simple faith subsequently corrupted by its institutionalization.” - ^ Thomas Jefferson, Notes on Virginia 1785

- ^ Ellis, Joseph. "American Sphinx". p.101-103, ISBN 0-679-44490-4

- ^ Thomas Jefferson. "Notes On the State Of Virginia, Religion". Jefferson believed the only legitimate role of government was to prevent injury to others. But to deny the existance of god or believe in 20 Gods was none of the state’s business.

- ^ Ellis, Joseph. "American Sphinx". p.101-103, ISBN 0-679-44490-4

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 81

- ^ Kolchin (1993), p. 81

- ^ Thomas Jefferson. "Notes On the State Of Virginia, Laws". Jefferson believed that the color of the skin was the primary difference between African Americans and Europeans in relation to beauty. He writes in "Laws," "The first difference which strikes us is that of colour." Jefferson believed that skin color was the foundation of "greater or lesser" beauty between the two races. Body symmetry and hair texture were other categories for determining beauty, according to Jefferson.

- ^ "David Walker's Appeal".

External links edit

- Notes on the State of Virginia, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- PDF version, The Online Library of Liberty.

- Notes on the State of Virginia, Digital facsimile of the manuscript copy for 1785 edition; Massachusetts Historical Society.

Category:Virginia culture

Category:Books by Thomas Jefferson

Editors of News Front, Contest For Power, US Presidential Elections 1789-1968, New York: Year Inc, 1968, p. 81