| Celilo Falls | |

|---|---|

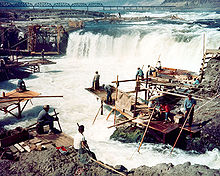

Dipnet fishing at Celilo Falls, looking east | |

| Location | Pacific Northwest United States |

| Coordinates | 45°39′08″N 120°58′06″W / 45.65230°N 120.96840°W |

| Type | Cascade |

| Number of drops | 3 |

| Watercourse | Columbia River |

| Average flow rate | 190,000 ft³/sec (5400 m³/s) |

Celilo Falls (Wyam, meaning "echo of falling water" or "sound of water upon the rocks," in several native languages[1]) was a waterfall and tribal fishing area on the Columbia River, just east of the Cascade Mountains, on what is today the border between the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington. Also known as The Chutes, Great Falls, or Columbia Falls[2], it was the first drop in a long series of rapids that culminated nine miles downstream in an area known as the Long Narrows or Big Dalles.[1] This nine-mile stretch of river was perhaps the greatest fishing site in North America[1] and was the location of the oldest continuously inhabited community on the continent until 1957, when the falls and nearby settlements were submerged by the construction of The Dalles Dam.[3]

Geography edit

Celilo Falls edit

Celilo Falls consisted of three main sections — a cataract known as Horseshoe Falls or Tumwater Falls, a deep eddy known as Cul-de-Sac, and the main channel.[4] The falls were formed by the Columbia River's relentless push through the basalt narrows of the Columbia River Gorge on the final leg of its journey to the Pacific Ocean. Frequently more than a mile (1.6 km) in width, the river was squeezed here into a width of only 140 feet (43 m).[5] The seasonal flow of the Columbia changed the height of the falls over the course of a year. At low water the drop was about 20 feet (6.1 m). During the spring freshet in June and July, the falls could be completely submerged. The falls were the sixth-largest by volume in the world and were among the largest in North America.[6] Average volume was 190,000 ft³/sec (5400 m³/s), and during periods of high water or flood, nearly a million ft³/sec (28,000 m³/s) passed over the falls, creating a tremendous roar that could be heard many miles away.[4]

The Narrows and The Dalles edit

Celilo Falls was the first in a series of cascades and rapids known collectively as The Narrows or The Dalles, stretching for about 9 miles (14 km) downstream.[1] Over that length, the river dropped 82 feet (25 m) at high water and 63 feet (19 m) at low water.[2] The rapids were interrupted by bare basalt islands — Threemile Reef, Grave, Wasco, Rabbit, Kiska, Big, and Chief — that diverted the river into eddies, whirlpools, and backwaters.[1]

Three miles (4.8 km) below Celilo Falls was a stretch of rapids known variously as the Short Narrows, Ten Mile Rapids, the Little (or Upper) Dalles, or Les Petites Dalles. These rapids were about 1 mile (1.6 km) long and 250 feet (76 m) wide. Ten miles (16 km) below Celilo Falls was another stretch of rapids, this one known as the Long Narrows, Five Mile Rapids, the Big (or Lower) Dalles, Les Grandes Dalles, or Grand Dalles. This stretch of rapids was about 3 miles (4.8 km) long, and the river channel narrowed to 75 feet (23 m). Immediately downstream were the Dalles Rapids (or Wascopam to the local natives), about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long. Here the river dropped 15 feet (4.6 m) in a tumult much commented on by early explorers.[2]

The Long Narrows and the Dalles Rapids are sometimes grouped together under names such as Grand Dalles, Les Dalles, Big Dalles, or The Dalles. One early observer, Ross Cox, noted a three-mile "succession of boiling whirlpools".[2] Explorer Charles Wilkes described it as "one of the most remarkable places upon the Columbia". He calculated that the river dropped about 50 feet (15 m) over 2 miles (3.2 km) here. During the spring freshet, the river rose as much as 62 feet (19 m), radically altering the nature of the rapids.[2] Fur trader Alexander Ross wrote, "[The water] rushes with great impetuosity; the foaming surges dash through the rocks with terrific violence; no craft, either large or small, can venture there safely. During floods, this obstruction, or ledge of rocks, is covered with water, yet the passage of the narrows is not thereby improved."[2]

History edit

Fishing and trading edit

For 11,000 years, native peoples gathered at Wyam to fish and exchange goods.[7] They built wooden platforms out over the water and caught salmon with dipnets and long spears on poles as the fish swam up through the rapids and jumped over the falls.[8] Historically, an estimated fifteen to twenty million salmon passed through the falls every year — chinook, coho, chum, pink, and sockeye — making it one of the greatest fishing sites in North America.[9] As many as 10,000 native people lived in dozens of small villages along the shoreline.[1]

Celilo Falls and the Long Narrows were strategically located at the border between Sahaptin and Chinookan speaking peoples and served as the center of an extensive trading network across the Pacific Plateau.[10] The Sahaptins lived in tule-mat villages at Celilo, while the upper Chinook lived in plankboard lodges at the Long Narrows to the west.[1] Artifacts from the area suggest that tribes came from as far away as the Great Plains, Southwestern United States, and Alaska to trade.[11] When the Lewis and Clark expedition passed through the area in 1805, the explorers found a "great emporium…where all the neighboring nations assemble," and a population density unlike anything they had seen on their journey.[12] Accordingly, historians have likened the Celilo area to the “Wall Street of the West."[13] The Wishram people lived on the north bank, while the Wasco lived on the south bank, with the most intense bargaining occurring at the Wishram village of Nix-luidix.[10] Charles Wilkes reported finding three major native fishing sites on the lower Columbia — Celilo Falls, the Big Dalles, and Cascades Rapids, with the Big Dalles being the largest. Alexander Ross described it as the "great rendezvous" of native traders, as "the great emporium or mart of the Columbia".[2]

edit

The seasonal changes in the Columbia's flow, high in summer and low in winter, affected Celilo Falls dramatically. Lewis and Clark reached the area in late autumn when the water was relatively low, making the falls into a major barrier. In contrast, when David Thompson passed Celilo Falls in July of 1811, the high water obscured the falls and made his passage through the Columbia Gorge relatively easy.[14]

In the 1840s and 1850s, American pioneers began arriving in the area, traveling down the Columbia on wooden barges loaded with wagons. Many lost their lives in the violent currents near Celilo.[15] The Wascopam Mission was established near the Dalles in 1838, followed by Fort Dalles in 1850, and then the town of The Dalles in 1856.[1] In the 1870s, the Army Corps of Engineers embarked on a plan to improve navigation on the river. In 1915, they completed the 14-mile Celilo Canal, a portage allowing steamboats to circumvent the turbulent falls. At the dedication of the canal, Portland investor and civic leader Joseph Nathan Teal gave voice to a common sentiment that endured for decades: “Our waters shall be free: free to serve the uses and purposes of their creation by a Divine Providence.”[16] However, the canal was scarcely used and was completely idle by 1919.[17]

Commercial fishing edit

The Dalles Dam edit

As more settlers arrived in the Pacific Northwest in the 1930s and 1940s, civic leaders advocated for a system of hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River. They argued that the dams would improve navigation for barge traffic from interior regions to the ocean; provide a reliable source of irrigation for agricultural production; provide electricity for the World War II defense industry; and alleviate the flooding of downriver cities. In 1938, the Bonneville Dam drowned an important salmon fishing site at Cascades Rapids, and in 1940, the Grand Coulee Dam submerged Kettle Falls. Celilo Falls was the last of the native dip-net fisheries on the Columbia River.[18]

As the war began, aluminum production, shipbuilding, and nuclear production at the Hanford site contributed to a rapid increase in regional demand for electricity. By 1943, fully 96 percent of Columbia River electricity was being used for war manufacturing.[19] In the eyes of the Army Corps of Engineers, the volume of water at Celilo Falls made The Dalles an attractive site for a new dam.

Throughout this period, native people continued to fish at Celilo, under the provisions of the 1855 Treaties signed with the Yakama Nation,[20] the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs,[21] and the Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Cayuse,[22] which guaranteed "the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed stations." In the 1940s, roughly two thousand native people still fished there.[18] Celilo Village was a town of about thirty permanent households on the Oregon side of the river.[1] The tribes and the Bureau of Indian Affairs protested the construction of a dam at The Dalles,[18] but in 1947, the federal government convened Congressional hearings and concluded that the proposed dam would not violate tribal fishing rights.[23] Subsequently, the government reached a monetary settlement with the affected tribes, paying $26.8 million for the loss of Celilo and other fishing sites on the Columbia.[24]

The Army Corps of Engineers commenced work on The Dalles Dam in 1952 and completed it five years later. On March 10, 1957, ten thousand people looked on as a rising Lake Celilo rapidly silenced the falls, submerged fishing platforms, and consumed the village of Celilo, ending an age-old existence for those who lived there.[1] The spectacle created bumper-to-bumper traffic along Highway 30 for nine hours.[1] The drowning of Celilo Falls has come to symbolize the dramatic transformation of the Columbia River from a wild salmon-bearing river to a highly controlled industrial waterway managed for hydroelectricity and navigation.[1] At the time, a reporter for The Dalles ''Chronicle'' compared it to the detonation of an atomic bomb.[1]

Legacy edit

Today, a small Native American community exists at nearby Celilo Village, on a bluff overlooking the former location of the falls. Celilo Falls retains great cultural significance for native peoples. Ted Strong of the Intertribal Fish Commission told one historian, "If you are an Indian person and you think, you can still see all the characteristics of that waterfall. If you listen, you can still hear its roar. If you inhale, the fragrances of mist and fish and water come back again."[25] In 2007, three thousand people gathered at Celilo Village to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of the inundation of the falls.[26]

Artist and architect Maya Lin is working on interpretive artwork at Celilo for the Confluence Project, scheduled for completion in 2009.[27][28]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Barber, Katrine (2005). Death of Celilo Falls. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gibson, James R. (1997). The Lifeline of the Oregon Country: The Fraser-Columbia Brigade System, 1811-47. University of British Columbia (UBC) Press. pp. 125–128. ISBN 0774806435. online at Google Books

- ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 52.

- ^ a b "World Waterfall database". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 80.

- ^ World Waterfall Database

- ^ Barber, Katrine (2001). Narrative Fractures and Fractured Narratives: Celilo Falls in the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center and the Yakama Nation Cultural Heritage Center. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 154.

- ^ Rohrbacher, George (January 2006). "Talk of the Past: The salmon fisheries of Celilo Falls". Common-Place. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ a b Ronda, James P. (1984). Lewis & Clark among the Indians. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Center for Columbia River History. "Oregon's Oldest Town: 11,000 Years of Occupation". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Cressman, L. S.; Cole, David L.; Davis, Wilbur A.; Newman, Thomas M.; Scheans, Daniel J. (1960). "Cultural Sequences at the Dalles, Oregon: A Contribution to Pacific Northwest Prehistory". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 50 (10): 1–108. doi:10.2307/1005853. hdl:2027/mdp.39076005656769. JSTOR 1005853.

- ^ Alpert, Emily (10 July 2006). "Remembering Celilo Falls". The Dalles Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Meinig, D.W. (1995) [1968]. The Great Columbia Plain (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Classic ed.). University of Washington Press. pp. pp. 37-38, 50. ISBN 0-295-97485-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Waiilatpu Mission Resource Education Guide" (Document). Whitman Mission National Historic Site. 14 November 2004.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ J. B. Tyrell, ed., David Thompson: Narrative of his Explorations in Western America, 1784-1812 (Toronto, 1916, 496-97; "Address of Joseph Nathan Teal, The Dalles-Celilo Celebration, Big Eddy, Oregon (May 5, 1915," Oregon Historical quarterly, 16 (Fall 1916), 107-8. (As quoted in The Columbia River's fate in the twentieth century)

- ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 204.

- ^ a b c White, Richard (1995). The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 100.

- ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 284.

- ^ "Treaty with the Yakama, 1855". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ "Treaty of Wasco, Columbia River, Oregon Territory with the Taih, Wyam, Tenino, & Dock-Spus Bands of the Walla-Walla, and the Dalles, Ki-Gal-Twal-La, and the Dog River Bands of the Wasco". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ "Treaty with the Walla Walla, Cayuse and Umatilla, 1855". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 378.

- ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 376.

- ^ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 378.

- ^ Modie, Jonathan. "The Celilo Legacy commemoration brought together the tribes of the lower Columbia River and others to remember Celilo Falls, bringing a mix of sadness and nostalgia". Wana Chinook Tymoo. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Egan, Timothy (4 August 2003). "Looking Backward and Ahead at Continent's End". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ "Confluence Project: Celilo Park". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

External links edit

- Recalling Celilo by Elizabeth Woody

- Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, includes Celilo Legacy commemoration and Celilo history

- Tangled Nets: Treaty Rights and Tribal Identities at Celilo Falls by Andrew H. Fisher

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Celilo Falls

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Dalles Rapids

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: The Dalles