| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

This article possibly contains original research. |

| Location | 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) northeast of Rashaya |

|---|---|

| Region | Bekaa Valley |

| Coordinates | 33°29′59″N 35°52′24″E / 33.49972°N 35.87333°E |

| Length | 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) |

| Width | 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) |

| Area | equivalent to 50 Sumerian Sar |

| History | |

| Builder | Qaraoun culture |

| Material | Jurassic limestone, karst topography |

| Founded | ca. 9500-8200 BCE |

| Abandoned | ca. 6000-5000 BCE with later settlements |

| Periods | ca. 9500-5000 BCE |

| Cultures | Roman, Greek, Qaraoun culture, Neolithic, PPNB, PPNA, Khiamian, Natufian |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Public access | Yes |

The Aaiha Hypothesis is a theory suggesting that there is a large Heavy Neolithic archaeological site of the Qaraoun culture, ruins of which exist in Aaiha, Lebanon. It suggests that this site was the central location of the Neolithic revolution, Emmer wheat and barley domestication events and recorded variously as the “Garden of the gods (Sumerian paradise)” or “Garden of Eden” in various subjective ancient texts.

The hypothesis was first suggested by exploration geologist Christian O'Brien in 1983 who called the location Achaia in his first book The Megalithic Odyssey. One peer review from John Barnatt marginalized O'Brien's later work with academia.[1] Edward F. Malkowski has recently discussed O'Brien's theories in 2006 in his book "The Spiritual Technology of Ancient Egypt", noting "O'Brien's book, The Genius of the Few, received little notice. A few scholars, however, including the British Museum Sumerian expert Irving Finkel, praised it. In 1996, British author Andrew Collins expounded on O'Brien's work in From the Ashes of Angels. He goes on to mention that "When these tablets, now stored at the University of Philadelphia museum, were first translated, they were believed to be a Sumerian creation myth, and the personalities depicted in the epic stories were interpreted as gods. According to exploration geologist and historian Christian O'Brien (1915-2001), however, this religious interpretation was a product of preconceived notions; according to his analysis, it has had 'disastrous results for the truth'."[2]

The hypothesis is being updated and expanded to make various reliable geographical, archaeological and mythological suggestions in order to promote further investigation and research of the Aaiha plain and various surrounding features such as suggested structural remains, irrigation watercourse and reservoir. The hypothesis supports the suggestion by Edward Robinson (scholar), that the site is one of the sources of the Hasbani (and therefore Jordan) river. It also supports the work of Mordechai Kislev and Moshe Feldman, who suggested that wheat and barley fist evolved and were possibly were domesticated in the vicinity of Mount Hermon.[3] It further suggests that the Aaiha plain was the location of the emmer and barley founder crops domestication event led by a single human group during the Neolithic revolution over a period of time possibly extending between the tenth until the sixth millennium BCE after which, the centre of culture moved to Eridu and Sumer. The location is connected to the physical remains of the Garden of the gods (Sumerian paradise), later known as the Garden of Eden. The Aaiha hypothesis proposes that ancestor worship of the people who lived in Aaiha was the inspiration for numerous religions and myths.

The hypothesis is aimed to help focus on investigation and conservation of this area where political instability has prevented virtually any substantial investigation over the last century. Full photographic (and unreleased video) records [1] are still subject to copyright problems after being unsuccessful in securing their release into the public domain.

Introduction edit

2009 Survey of Aaiha edit

In November 2009, along with Karl Guildford, Paul Bedson conducted an initial survey[2] and video documentary of Aaiha plain (or basin), in particular a 1 mile (1.6 km) long, completely straight section of rock-cut watercourse.[3] This feature was fisrt charted in 1984,[4][5] then surveyed with Space archaeology in southern Lebanon on Google Earth in 2006 by Edmund Marriage (the nephew of Christian O'Brien), who helped direct the survey. The central hill with ruins shown being destroyed by building work between 2005-2010 shown here [6]. The underground river in Aaiha leads to the Hasbani and was suggested to be the geographical source of the Jordan by Edward Robinson as well as the literary source of the Hubur. The basin is the same dimensions recorded in the myth or Enlil and Ninlil to measure fifty Sumerian sar, eqivalent to 2,000 square metres (22,000 sq ft) and lies between Rashaya al-Wadi and Kfar Qouq. The central and highest foothill on a dividing ridge to the north of the plain is suggested to be the location of the original Hursag (as in Ninhursag) still showing some remains and limestone plaster suggested to have been the "mountain house" or Ekur in Eden. This is suggested to be an administrative centre for a neolithic settlement and origin to the stories about the Garden of Eden or Dilmun by radical scholar Christian O'Brien. The Aaiha hypothesis suggests an archaeological "megasite" is located in the Aaiha plain in the Beqaa Valley where key events of the Neolithic Revolution are suggested to have been centered, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) north of Mount Hermon. There are also significant remains of an ancient 600,000,000 US gallons (2.3×109 L) reservoir to the west of Kfar Qour that links to the ancient watercourse and was shown to the survey team by the council leader of Rashaya, Kamal El-Sahili.

Eden in Lebanon edit

The prophet Ezekiel mentions that the trees in the Garden of Eden come from Lebanon (Ezekiel 31:15–18). Based on an analysis of this chapter, Terje Stordalen has suggested "an apparent identification of Eden and Lebanon in Ezekiel 31" and symbolical relationships between Eden and Lebanon.[4] John Pairman Brown wrote "it appears that the Lebanon is an alternative placement in Phoenician myth (as in Ez 28,13, III.48) of the Garden of Eden".[5] and Paul Swarup also discusses connections between paradise, the garden of Eden and the forests of Lebanon (possibly used symbolically) within prophetic writings.[6]

Geography of Aaiha edit

Underground river to the Hasbani, the chasm of the Abzu edit

During the 2009 survey, the Lebanese Red Cross in Rashaya, notably Hari and his father met with the surveyors and Rami Olaby, their guide. They marked on a map the northeast cavern in the Aaiha plain. The red cross team leader claimed that they had put red dye into the cavern during the last flooding of the temporary wetland. The dye was reported to have emerged in the Hasbani river to the southwest. A similar phenomenon was noted in 1856 by Edward Robinson (scholar) during a visit to the location where he surveyed the smaller southwest fountain and compared it to the myth in Josephus about the Chaff of Phiala.

Aaiha (or Aiha) is a village, plain, lake and temporary wetland situated in the Rashaya District and south of the Beqaa Governorate in Lebanon.[7][8] It is located in an intermontane basin near Mount Hermon and the Syrian border, approximately halfway between Rashaya and Kfar Qouq.[9]

The village sits ca. 3,750 feet (1,140 m) above sea level and the small population is predominantly Druze.[9][10] Wild wheats Triticum boeoticum and T. urartu grow in this area, also used for farming goats.[11][12] There is a nearby tomb of a muslim saint and a Roman ruins thought to be a temple or citadel that is now totally destroyed[9][13][14][15] Fragments of blocks and inscribed stones lie around the area, some having been used in the village dwellings and others covered in rubbish in the surrounding area.[16] Dr. Edward Robinson and Reverend Eli Smith visited in 1852 and noted some of the stones were large, unbevelled and well hewn.[9] Sir Charles Warren also later visited and documented the area as part of an archaeological survey in 1869.[17] The temple was completed in 92 AD but only the western part remained when visited, located on the top of a hill overlooking the plain.[18][19] It was constructed of blue limestone with an entrance opening facing east and a sideways bearing of 78°30'. It has a cornice and base with Roman features in the Corinthian style and a frieze of the same style was laid nearby at the time of the survey. A stone with a Greek inscription was found built into the western wall. The structure measures 37.6 feet (11.5 m) wide by at least 47.15 feet (14.37 m) long with an entrance to vaults underneath. A column found nearby measured 3.2 feet (0.98 m) in diameter.[19]

The village is situated on a ridge next to Aaiha plain, Aaiha lake or Aaiha temporary wetland, which forms a near perfect circlular shape, approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) in diameter and enclosed by mountains and the ridge on the west.[9][20] The plain is completely level with no particularly visible outlet for water, which occasionally floods the basin to a depth of several feet to form a lake. The creation of the lake is assisted by fountains that well up through a large chasm in the northwest and a smaller fissure in the southeast. It has also been noted that when the waters subside, they drain down these fissures. Investigative potholers have claimed a permanent stream flows underneath these fissures. The smaller southeastern fissure was investigated and found to be 15 feet (4.6 m) in diameter, 8 feet (2.4 m) to 10 feet (3.0 m) deep with no sign of water at the bottom. Robinson did not record any investigation of the larger one to the northwest of the plain, which was not flooded at the time, during the Summer.[9] The villagers suggest the underground stream leads to and is the original source and fountain of the Hasbani river, the most northern source of the Jordan river. This is notably similar to that described in the tale of "The Chaff of Phiala" in "The Jewish War" by Flavius Josephus.[9] Josephus tells a geographically innacurate tale of a cavern in an ancient place called Phiala or Phiale (modern Birkat Ram), discovered to be the initial source of the Jordan by Philip the Tetrarch of Trachonitis.[21] He threw chaff into Phiala and found it was carried by the waters to Panium (modern Banias), previously thought to be the origin of the Jordan river.[22] Josephus writes:

| “ | Now Panium is thought to be the fountain of the Jordan, but in reality it is carried thither after an occult manner from the place called Phiala : This place lies as you go up to Trachonitis, and is an hundred and twenty furlongs from Caesarea, and is not far out of the road on the right hand ; and indeed it hath its name of Phiala (vial or bowl) very justly, from the roundness of its circumference, as being round like a wheel; its water continues always up to its edges, without either sinking or running over. And as this origin of the Jordan was formerly not known, it was discovered so to be when Philip was Tetrarch of Trachonitis ; for he had chaff thrown into Phiala, and it was found at Panium where the ancients thought the fountain head of the river was, whither it had been therefore carried (by the waters). [22] | ” |

Edward Robinson commented that this story would appear still current in respect to this chasm and underground stream leading to the Hasbani.[9] Some neolithic flints have been recovered in this area, in the hills 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) north of Rashaya.[23]

Kfar Qouq - The Pottery Place edit

Kfar Qouq (and variations of spelling) is a village in Lebanon, situated in the Rashaya District and south of the Beqaa Governorate. It is located in an intermontane basin near Mount Hermon near the Syrian border, approximately halfway between Jezzine and Damascus.[24]

The population of the hillside village is predominantly Druze.[25] It contains two Roman temple sites in the Western section of the town dating to around 111 BC[26] and another less preserved temple near the church.[27] Fragments such as columns and an inscribed block have been re-used in the village and surrounding area.[28] The surrounding area also has many stone basins, tombs, caves, rock cut niches and other remnants from Greek and Roman times.[29] Dr. Edward Robinson, visited in the Summer of 1852 and noted a Greek inscription on a doorway, the public fountain and a large reservoir which he noted "exhibits traces of antiquity". The name of the village means "the pottery place" in Aramaic and has also been known as Kfar Quq Al-Debs in relation to molasses and grape production in the area. Kfar Qouq also been associated with King Qouq, a ruler in ancient times.[30] The local highway was targeted in the 2006 Lebanon War between Hezbollah and Israel.[31]

Limestone White Ware - the first prototype pottery edit

The Aaiha hypothesis suggests the first prototype of pottery could have developed using pyrotechnology to create White Ware from the limestone in the area of Aaiha. White Ware is a crumbly form of proto-pottery was manufactured by pulverizing limestone, then heating it to a temperature in excess of 1000 °C. This reduced it to lime from which could be mixed with ashes, straw or gravel and made into a grey lime plaster.[32] The plaster was initially so soft that it could be moulded, before hardening through air drying into a rigid cement. The plaster was moulded into vessels by coiling to serve some of the functions of later clay pottery. White Ware vessels tended to be rather large and coarse, often found in the dwelling rooms where they were made indicating their use for stationary storage of dry goods.[33] Designs included a range of large and heavy rectangular tubs, circular vessels and smaller bowls, cups and jars.[34] Imprints of basketry on the exterior of some vessels suggest that some were shaped into large basket shapes.[35] It is likely these larger vessels were mainly used for dry goods storage.[33] Some of the White Ware vessels found were decorated with incisions and stripes of red ochre.[34][36] Other uses of this material included plastering of skulls and as a floor or wall covering.[37] Some lime plaster floors were also painted red, and a few were found with designs imprinted on them.[38]

White Ware was commonly found in PPNB archaeological sites in Syria such as Tell Aswad, Tell Abu Hureyra, Bouqras and El Kowm.[33] Similar sherds were excaveated at Ain Ghazal in northern Jordan.[39][40] White pozzolanic ware from Tell Ramad and Ras Shamra is considered to be a local imitation of these limestone vessels.[41] It was also evident in the earliest neolithic periods of Byblos, Hashbai, Labweh, Tell Jisr and Tell Neba'a Faour in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon.[42] It has been noted that this type of pottery was more prevalent and dated earlier in the Beqaa than at Byblos.[23] A mixed form was found at Byblos where the clay was coated in a limestone slip, in both plain and shell combed finishes.[41] The similarities of White Ware and overlapping time periods with later clay firing methods have suggested that Dark Faced Burnished Ware, the first real pottery, came as a development from this limestone prototype.[43][43]

Archaeology of Aaiha edit

The ASPRO chronology developed by the Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée gives the latest and most reliable chronology of the Neolithic period during the holocene. It is a nine period dating system of the ancient Near East used for archaeological sites aged between 14000 and 5700 BP.[42]

ASPRO stands for the "Atlas des sites Prochaine-Orient" (Atlas of Near East archaeological sites), a French publication pioneered by Francis Hours and developed by other scholars such as Oliver Aurenche.

The periods, cultures, features and date ranges of the ASPRO chronology are shown below:

| ASPRO Period | Names | Dates |

| Period 1 | Natufian, Zarzian final | 12000-10300 BP or 12000-10200 cal. BCE |

| Period 2 | Protoneolithic, Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), Khiamian, Sultanian, Harifian | 10300-9600 BP or 10200-8800 cal. BCE |

| Period 3 | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), PPNB ancien | 9600-8000 BP or 8800-7600 cal. BCE |

| Period 4 | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), PPNB moyen | 8000-8600 BP or 7600-6900 cal. BCE |

| Period 5 | Dark Faced Burnished Ware (DFBW), Çatal Hüyük, Umm Dabaghiyah, Sotto, Proto-Hassuna, Ubaid 0 | 8000-7600 BP or 6900-6400 cal. BCE |

| Period 6 | Hassuna, Samarra, Halaf, Ubaid 1 | 7600-7000 BP or 6400-5800 cal. BCE |

| Period 7 | Pottery Neolithic A (PNA), Halaf final, Ubaid 2 | 7000-6500 BP or 5800-5400 cal. BCE |

| Period 8 | Pottery Neolithic B (PNB), Ubaid 3 | 6500-6100 BP or 5400-5000 cal. BCE |

| Period 9 | Ubaid 4 | 6100-5700 BP or 5000-4500 cal. BCE |

| The Stone Age |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene) |

|

| ↓ Chalcolithic |

The Aaiha hypothesis suggests that the founders and inhabitants of the settlement at Aaiha were the Qaraoun culture, which became dominant in the Beqaa Valley and is associated with Heavy Neolithic and possibly Trihedral Neolithic (and possibly later Shepherd Neolithic) flint and stone industries. It further suggests that these Heavy Neolithic axes, picks and adzes were used for tree felling and timber work. Likely for forested, high altitude sites to develop sedentary agricultural settlements. The Aaiha hypothesis further links the Qaraoun culture to the Sultanian PPNA famously discovered at Jericho in the 1950s excavations by Kathleen Kenyon. It is suggested that the Trihedral Neolithic flints found in Lebanon were the "rock mauls", suggested to have been required to build the massive stoneworks of this era such as the 600m rock cut ditch at Jericho, the Wall of Jericho, Tower of Jericho and with the rock cut watercourse ruins at Aaiha.

Qaraoun culture edit

The Qaraoun culture is a culture of the Lebanese Stone Age around Qaraoun in the Beqaa Valley.[44] The Gigantolithic or Heavy Neolithic flint tool industry of this culture was recognized as Neolithic by Henri Fleisch and confirmed by A. Rust and Dorothy Garrod.[45]

Qaraoun II edit

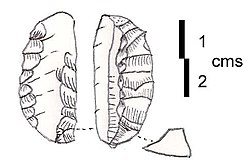

Qaraoun II is the type site of the Neolithic Qaraoun culture in the Beqaa valley. It is located on top of a gorge on the right of the river. A large area of the site is now completely destroyed but a large collection of flints was collected by workers and examined by Jacques Cauvin and Marie-Claire Cauvin. The collection includes a full range of Heavy Neolithic material with oval, almond shaped and rectangular axes, trapezoidal and rectangular chisels, thick discoid, side and end scrapers on large blades, picks and burins and a full range of cores. The Cauvins suggested the material had similarities to the Neolithic moyen assemblage from Byblos and Andrew Moore theorized that Heavy Neolithic stations such as this were used during earlier and later periods.[23] James Mellaart suggested the Heavy Neolithic industry of the culture dated to a period before the Pottery Neolithic at Byblos (10600 to 6900 BCE according to the ASPRO chronology).[46]

Heavy and Trihedral Neolithic edit

Heavy Neolithic (alternatively, Gigantolithic) is a style of large flint tools (or industry) associated primarily with the Qaraoun culture in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon, dating to the Epipaleolithic or early Pre-pottery Neolithic at the end of the Stone Age.[44] The type site for the Qaraoun culture is Qaraoun II. Other sites with Heavy Neolithic finds include Adloun II, Akbiyeh, Beit Mery II, Dikwene II, Jbaa, Jebel Aabeby, Jedeideh I, Mtaileb I (Rabiya), Ourrouar II, Sin el Fil, Tell Mureibit near Kasimiyeh, and possibly Sidon III. Some found in the Beqaa Valley include Nabi Zair, Tell Khardane, Mejdel Anjar I, Dakoue, Kefraya, Tell Zenoub, Kamed Loz I, Bustan Birke, Joub Jannine III, Amlaq Qatih, Kafr Tibnit, Tayibe, Taireh II, Khallet Michte I, Khallet Hamra and Douwara.[23]

The term "Heavy Neolithic" was translated by Lorraine Copeland and Peter J. Wescombe from Henri Fleisch's term "gros Neolithique", suggested by Dorothy Garrod for adoption to describe a particular flint industry that was identified at sites near Qaraoun in the Beqaa Valley.[47] The industry was also termed "Gigantolithic" and confirmed as Neolithic by A. Rust and Dorothy Garrod.

The industry was initially mistaken for Acheulean or Levalloisian by some scholars. Diana Kirkbride and Henri de Contenson suggested that it existed over a wide area of the fertile crescent. The industry occurred before the invention of pottery and is characterized by huge, coarse, heavy tools such as axes and adzes including bifaces. There is no evidence of polishing at the Qaraoun sites or indeed of any arrowheads, burins or millstones. Henri Fleisch noted that the culture that produced this industry may well have led a forest way of life before the dawn of agriculture.[48] Jacques Cauvin proposed that some of the sites discovered may have been factories or workshops as many artifacts recovered were rough outs.[49] James Mellaart suggested the industry dated to a period before the Pottery Neolithic at Byblos (10600 to 6900 BCE according to the ASPRO chronology).[50] The industry was excavated at Aadloun II (Bezez Cave) by Diana Kirkbride and Dorothy Garrod. It has also shown noticeable similarities to an industry found in the Wadi Farah sites by Francis Turville-Petre and was likened to the Campignian.[51]

The industry has been found at surface stations in the Beqaa Valley and on the seaward side of the mountains. Heavy Neolithic sites were found near sources of flint and were thought to be factories or workshops where large, coarse flint tools such as axes and adzes were roughed out to work and chop timber. Chisels, flake scrapers and picks were also found with little, if any sign of arrowheads, sickles or pottery. Finds of waste and debris at the sites were usually plentiful, normally comprising of orange slices, thick and crested blades, discoid, cylindrical, pyramidal or Levallois cores. It has been likened to the Campignian industry.[23]

-

Massive nosed scraper on a flake with irregular jagged edges, notches and "noses".

-

Double ended pick, triangular section with narrowing, jagged edges at both ends.

-

Massive steep-scraper on a split cobble or flake with direct retouch all around and cortex on the crest.

-

Thick and heavy biface, retouched all over with jagged and irregular edges.

Trihedral Neolithic is a name given by archaeologists to a style (or industry) of striking spheroid and trihedral flint tools from the archaeological site of Joub Jannine II in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon.[52] The style appears to represent a highly specialized Neolithic industry. Little comment has been made of this industry.[44]

Orange slice is an early sickle blade element made out of flint.[53] The flints are so called due to their shape, which resembles a segment of an Orange. This sickle industry has no evidence of developed denticulation.[44] Orange slices were used for harvesting plants at the start of the Neolithic revolution and were particularly prevalent in Lebanon where they were found alongside Gigantolithic choppers of the Qaraoun culture in and around Qaraoun in the south of the country. Sites where orange slices have been found include Majdel Anjar I, Dakwe I and II, Habarjer III, Qaraoun I and II, Kefraya, and Beı'dar Chamou't.[54]

A Canaanean blade is an archaeological term for a long, wide blade made out of stone or flint, predominantly found at sites in Lebanon (ancient Canaan). They were first manufactured and used in the Neolithic Stone Age to be used as weapons such as javelins or arrowheads. The same technology was used during the later Chalcolithic period in the production of broad sickle blade elements for harvesting of crops.[44]

Neolithic hoes at Kaukaba and their relationship to Enlil, creator in the Song of the hoe edit

Kaukaba, Kaukabet El-Arab or Kaukaba Station is a Neolithic archaeological site East of Majdel Balhis near Rashaya in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon. It was first found by P. Billaux in 1957 who alerted Jesuit Archaeologists, Fathers Henri Fleisch and Maurice Tallon. Open air site excavations by L. and Frank Skeels were also carried out in 1964.[55] The rock shelter site lies amongst fields covered with basalt boulders from ancient lava flows. It is in a low pass from the Karaoun Dam to Rashaya. This area is close to the 4 heads of the Jordan River and is drained by feeders such as the Dan, Banias, Hasbani and Upper Jordan rivers, North of Hasbaya.[56][23] Artefacts found on the surface included flint axes, sickles, obsidian, basalt vessels and arrowheads. Prominent artefacts found included a series of flint picks with heavily worn points due to extremely heavy usage. Fragments of agricultural tools such as basalt hoes have been found with very slight dating suggesting the 6th millennium or earlier. Flints were not knapped on site and the centre of the hoe production has not yet been found.[57][58][59]

The Sumerian myth, the Song of the hoe starts with a creation myth where Enlil separates heaven and earth in Duranki, the cosmic Nippur or 'Garden of the Gods'.

"Not only did the lord make the world appear in its correct form, the lord who never changes the destinies which he determines – Enlil – who will make the human seed of the Land come forth from the earth – and not only did he hasten to separate heaven from earth, and hasten to separate earth from heaven, but, in order to make it possible for humans to grow in "where flesh came forth" [the name of a cosmic location], he first raised the axis of the world at Dur-an-ki.[60]

The myth continues with a description of Enlil creating daylight with his hoe; he goes on to praise its construction and creation.

The nearby sites: Jericho, Tell Aswad, Tell Ramad, Iraq ed-Dubb and Labweh edit

Tell Aswad is an example of one of the oldest sites of agriculture with domesticated emmer wheat dated by Willem van Zeist and his assistant Johanna Bakker-Heeres to 8800 BCE.[61][62] Peter Akkermans and Glenn Schwatrz suggested on this evidence that Tell Aswad shows "the earliest systematic exploitation of domesticated cereals (emmer wheat) c. 9000-8500 BC". They suggest that the arrival of domesticated grain came from somewhere in the vicinity of "the basaltic highlands of the Jawlan (Golan) and Hawran".[63] The claim is based on the discovery of enlarged grains, absences of wild grains and on the presumption that the site was beyond the usual habitat of the wild variety of emmer wheat. The earliest postulated evidence for einkorn wheat at Jericho was not dated until at least five hundred years later than Aswad's emmer.[64] Flax seeds were also present. Fruit, figs and pistachios, were apparently very popular because they were found in large quantities. Stationary containers of mud and stone were found with carbonized grain fond on the interior of one designating them as silos. Tell Aswad has been cited as being of importance for the evolution of organised cities due to the appearance of building materials, organized plans and collective work. It has provided insight into the "explosion of knowledge" in the northern Levant during the PPNB Neolithic stage following dam construction.[65] Aswad has been suggested to be amongst the ten probable centers for the origin of agriculture.[66]

Andrew Moore suggested that dawn of the neolithic revolution originated over long periods of development in the Levant, possibly beginning during the Epipaleolithic. In "A Reassessment of the Neolithic Revolution", Frank Hole further expanded the relationship between plant and animal domestication. He suggested the events could have occurred independently over different periods of time, in as yet unexplored locations. He noted that no transition site had been found documenting the shift from what he termed immediate and delayed return social systems. He noted that the full range of domesticated animals (goats, sheep, cattle and pigs) were not found until the sixth millennium at Tell Ramad. Evidenced by arguments such as those by Maria Hopf regarding cultivated emmer and barley at Jericho, along with the earliest emmer suggested by Willem van Zeist at Tell Aswad, Hole concluded that "close attention should be paid in future investigations to the western margins of the Euphrates basin, perhaps as far south as the Arabian Peninsula, especially where wadis carrying Pleistocene rainfall runoff flowed."[67]

Archaeobotany - Emmer and Barley domestication event location edit

Emmer

Graham Wilcox et al write "Wild emmer wheat was recognized in 1873 by Fredrich August Körnicke, a German Agro-Botanist, in the herbarium of the National Museum of Vienna.[68] He found it among the specimiens of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) that were collected by the botanist Theodor Koyschy in 1855 in Rashaya on the northwestern slope of Mount Hermon.[69] Körnicke described this plant specimen in 1889 as wild emmer wheat (Triticum vulgare var dicoccoides).[68] He also recognized that this plant is the wild progenitor 'prototype' of cultivated wheat".[70] Concluding "Archaeobotanical studies strongly suggest that wild emmer was possibly twice and independently taken into cultivation: (1) in the southern Levant and (2) in the northern Levant."[71][72][73] Wilcox writes that "According to Feldman and Kislev, the hybridization could have occurred in the vicinity of Mount Hermon and the catchment area of the Jordan River because of the larger morphological, phenological, biochemical and molecular variation of wild emmer from southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq or southwestern Iran."[74][75]

Mordechai Kislev and Moshe Feldman suggested that wild emmer evolved around three to five hundred thousand years ago in the vicinity of Mount Hermon because of wider molecular, biochemical and morphological variation in wheat from this area. Their review of archaeological evidence in 2007 defined the northern Levant from the Taurus mountains to the middle Euphrates and southern Levant from the Damascus basin to the lower Rift Valley. They suggested that wild emmer was first cultivated in the southern Levant sites of Gilgal I, Netiv Hagdud, Iraq ed-Dubb, ZAD 2, Tell Aswad and Jericho. In the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, a mixture of both wild and domesticated emmer with non-brittle rachis were detected at sites such as Nahal Heimar, Ein Ghazal, Beidha, Tell Aswad and Jericho in the south and Dejade, Nevali Cori, Cafer Hoyuk, Cayonu, Abu Hureyra, Jarmo and Ali Kosh in the north. By the late PPNB, free-threshing wheat evolved in both regions at sites such as Tell Ramad, Tell Ghoraife, Azraq, El Kowm and Atlit-Yam in the south and Tell Halula, Cafer Hoyuk, Cayonu, Sabi Abyad, Can Hasan, Ras Shamra and Bouqras in the north.[76]

Luo et al suggested that emmer was domesticated in the Karacadag area in 2007 following restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis from 131 sites. Alternative views have been raised that it was also domesticated independently in the southern Levant. Various other scholars have supported the theory that genetic testing methods may indicate a choice of monophyletic (single site), diphyletic (two site) or polyphyletic (multi-site) origins of domesticated emmer.[77]

Barley

Following the work of Daniel Zohary studying the differentiation and composition of alleles in barley, Badr et al concluded that cultivated barley had a single origin through analysis of neighbor-joining clustering, based on distance among amplified fragment length polymorphism genotypes. Peter Morrell and Michael Clegg have argued for two domestication events for this founder crop.[78][79][80]

Mythology of Aaiha edit

Ancestor worship in ancient Sumer edit

The sun god is only modestly mentioned in Sumerian mythology with one of the notable exceptions being the Epic of Gilgamesh. In the myth, Gilgamesh seeks to establish his name with the assistance of Utu, because of his connection with the cedar mountain. Gilgamesh and his father, Lugalbanda were kings of the first dynasty of Uruk, a lineage that Jeffrey H. Tigay suggested could be traced back to Utu himself. He further suggested that Lugalbanda's association with the sun-god in the Old Babylonian version of the epic strengthened "the impression that at one point in the history of the tradition the sun-god was also invoked as an ancestor".[81]

Myths recording Aaiha edit

Sumerian Cuneiform Cylinder similar to the "Barton Cylinder" | |

| Author | George Aaron Barton |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Language, Sumerology, Cuneiform studies, Translation |

| Publisher | Yale University Press, Oxford University Press |

Publication date | August 1918 |

| Media type | print (hardback) |

| Pages | 177pp (first edition) |

| ISBN | 978-1148598970 |

| OCLC | 2539495 |

| 492/.1 | |

| LC Class | PJ3711 .Y34 1983 |

Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions is a 1918, Sumerian linguistics and mythology book written by George Aaron Barton.[82]

It was first published by Yale University Press in the United States and deals with commentary and translations of twelve cuneiform, Sumerian myths and texts discovered by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology excavations at the temple library at Nippur.[83] Many of the texts are extremely archaic, especially the Barton Cylinder, which Samuel Noah Kramer suggested may date as early as 2500 BC.[84] A more modern dating by Joan Goodrick Westenholz has suggested the cylinder dates to around 2400 BC.[85]

Contents

Some of the myths contained in the book suggested to record details of the Aaiha settlement are shown below:

| Modern title | Museum number | Barton's title |

|---|---|---|

| Debate between sheep and grain | 14,005 | A Creation Myth |

| Barton Cylinder | 8,383 | The oldest religious text from Babylonia |

| Enlil and Ninlil | 9,205 | Enlil and Ninlil |

| Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D) | 11,065 | A hymn to Dungi |

| Old Babylonian oracle | 8,322 | An Old Babylonian oracle |

| Kesh temple hymn | 8,384 | Fragment of the so-called "Liturgy to Nintud" |

| Debate between Winter and Summer | 8,310 | Hymn to Ibbi-Sin |

| Hymn to Enlil | 8,317 | An excerpt from an exorcism |

| Lament for Ur | 19,751, 2,204, 2,270 & 2,302 | A prayer for the city of Ur |

Kesh temple hymn edit

In the Kesh temple hymn, the first recorded description (c. 2600 BC) of a domain of the gods is a garden The four corners of heaven became green for Enlil like a garden."[60] In an earlier translation of this myth by George Aaron Barton in Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions he considered it to read "In hursag the garden of the gods were green."[82]

Atrahasis edit

Sumerian paradise is described as a garden in the myth of Atrahasis where lower rank deities (the Igigi) are put to work digging a watercourse by the more senior deities (the Annanuki).[86]

When the gods, like man. Bore the labour, carried the load. The gods' load was great, the toil greivous, the trouble excessive. The great Annanuki, the Seven, Were making the Igigu undertake the toil.[87]

The Igigi then rebel against the dictatorship of Enlil, setting fire to their tools and surrounding Enlil's great house by night. On hearing that toil on the irrigation channel is the reason for the disquiet, the Annanuki council decide to create man to carry out agricultural labour.[87]

Debate between sheep and grain edit

Another Sumerian creation myth, the Debate between sheep and grain opens with a location "the hill of heaven and earth", and describes various agricultural developments in a pastoral setting. This is discussed by Edward Chiera as "not a poetical name for the earth, but the dwelling place of the gods, situated at the point where the heavens rest upon the earth. It is there that mankind had their first habitat, and there the Babylonian Garden of Eden is to be placed."[88] The Sumerian word Edin, means "steppe" or "plain",[89] so modern scholarship has abandoned the use of the phrase "Babylonian Garden of Eden" as it has become clear the "Garden of Eden" was a later concept.

Epic of Gilgamesh edit

The Epic of Gilgamesh describes Gilgamesh travelling to a wondrous garden of the gods that is the source of a river, next to a mountain covered in cedars, and references a "plant of life". In the myth, paradise is identified as the place where the deified Sumerian hero of the flood, Utnapishtim (Ziusudra), was taken by the gods to live forever. Once in the garden of the gods, Gilgamesh finds all sorts of precious stones, similar to Genesis 2:12:

There was a garden of the gods: all round him stood bushes bearing gems ... fruit of carnelian with the vine hanging from it, beautiful to look at; lapis lazuli leaves hung thick with fruit, sweet to see ... rare stones, agate and pearls from out the sea.[90]

Song of the hoe edit

The Song of the hoe features Enlil creating mankind with a hoe and the Annanuki spreading outward from the original garden of the gods. It also mentions the Abzu being built in Eridu.[60]

Hymn to Enlil edit

A Hymn to Enlil praises the leader of the Sumerian pantheon in the following terms:

You founded it in the Dur-an-ki, in the middle of the four quarters of the earth. Its soil is the life of the Land, and the life of all the foreign countries. Its brickwork is red gold, its foundation is lapis lazuli. You made it glisten on high.[91]

Dilmun as the Aaiha plain edit

Sumerian paradise has sometimes been associated with Dilmun. Sir Henry Rawlinson first suggested the geographical location of Dilmun was in Bahrain in 1880.[92] This theory was later promoted by Frederich Delitzsch in his book Wo lag dar Paradies in 1881, suggesting that it was at the head of the Persian Gulf.[93] Various other theories have been put forward on this theme. Dilmun is first mentioned in association with Kur (mountain) and this is particularly problematic as Bahrain is very flat, having a highest prominence of only 134 metres (440 ft) elevation.[92] Also, in the early epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, the construction of the ziggurats in Uruk and Eridu are described as taking place in a world "before Dilmun had yet been settled". In 1987, Theresa Howard-Carter realized that the locations in this area possess no archaeological evidence of a settlement dating 3300-2300 BC. She proposed that Dilmun could have existed in different eras and the one of this era might be a still unidentified tell.[94][95] Thorkild Jacobsen's translation of the Eridu Genesis calls it "Mount Dilmun" which he locates as a "faraway, half-mythical place".[96]

Garden of the gods (Sumerian paradise) - physical features on the ground edit

Reservoir, Watercourse, Great house site, Granary (temple) site, hut circles, Northeast chasm, Southwest chasm.

In tablet nine of the standard version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh travels to the garden of the gods through the Cedar Forest and the depths of Mashu, a comparable location in Sumerian version is the "Mountain of cedar-felling".[97][98][99] Little description remains of the "jewelled garden" of Gilgamesh because twenty four lines of the myth were damaged and could not be translated at that point in the text.[100]

The name of the mountain is Mashu. As he arrives at the mountain of Mashu, Which every day keeps watch over the rising and setting of the sun, Whose peakes reach as high as the "banks of heaven," and whose breast reaches down to the netherworld, The scorpion-people keep watch at its gate.[98]

Bohl has highlighted that the word Mashu in Sumerian means "twins". Jensen and Zimmern thought it to be the geographical location between Mount Lebanon and Mount Hermon in the Anti-Lebanon range.[98] Edward Lipinski and Peter Kyle McCarter have suggested that the garden of the gods relates to a mountain sanctuary in the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges.[101][102] Other scholars have found a connection between the Cedars of Lebanon (pictured) in the forest of the Cedars of God and the garden of the gods. The location of garden of the gods is close to the forest, which is described in the line:

Saria (Sirion / Mount Hermon) and Lebanon tremble at the felling of the cedars.[103][104]

John Day noted that Mount Hermon is the "highest and grandest of the mountains in the area, indeed in the whole of Palestine" at 2,814 metres (9,232 ft) elevation considering it the most likely to contrast with the abzu, or depths of the sea. Day provided support for Lipinski's suggestion that Mount Hermon was the dwelling place for the Annanuki, suggesting this was also the location of Bashan in Psalm 68 (Psalms 68:15–22).[105] He also noticed that the sons of God are introduced descending from Mount Hermon in 1 Enoch (1En6:6).[105] There is a Caananite narrative myth from Phonecia called the "Fall of the day star" that describes the inglorious fall of Helel ben Shahar and another Ugaritic myth called the Baal cycle about the fall of the god Attar from Saphon (Hermon) which both deal with the "invasion of the garden of gods in the Lebanon".[106] These have been suggested to provide the background and origin of the story about the fall of Lucifer from heaven, told in the Book of Isiah (Isiah 14:4–21) "Yea, the cypresses rejoice at thee, and the cedars of Lebanon, saying, 'Since thou art laid down, no feller is come up against us'" and "How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning".[103][107][108][109] In the myths, the intruder enters into the sacred space of the garden and lays hands on God's tree, not the same Cedar of Lebanon mentioned by Ezekiel (Ezekiel 31:15–18), but a sacred place invaded by an arrogant and presumptuous human, trying to take the position of the gods, from where he is banished to hell.[103]

In the Gudea cylinders, Cedars of Lebanon are apparently floated down from Lebanon on the Euphrates and the "Iturungal" canal to Girsu.{{cquote|"To the mountain of cedars, not for man to enter, did for Lord Ningirsu, Gudea bend his steps: its cedars with great axes he cut down, and into Sharur ... Like giant serpents floating on the water, cedar rafts from the cedar foothills."[96] He is then sent a third dream revealing the different form and character of the temples. The construction of the structure is then detailed with the laying of the foundations involving participation from the Annanuki including Enki, Nanse, Bau. Different parts of the temple are described along with its furnishings and the cylinder concludes with a hymn of praise to it.[110]

Lines 738 to 758 describes the house being finished with "kohl" and a type of plaster from the "edin" canal:

"The fearsomeness of the E-ninnu covers all the lands like a garment. The house! It is founded by An on refined silver, it is painted with kohl, and comes out as the moonlight with heavenly splendor. The house! Its front is a great mountain firmly grounded, its inside resounds with incantations and harmonious hymns, its exterior is the sky, a great house rising in abundance, its outer assembly hall is the Annunaki gods place of rendering judgments, from its ...... words of prayer can be heard, its food supply is the abundance of the gods, its standards erected around the house are the Anzu bird (pictured) spreading its wings over the bright mountain. E-ninnu´s clay plaster, harmoniously blended clay taken from the Edin canal, has been chosen by Lord Nin-jirsu with his holy heart, and was painted by Gudea with the splendors of heaven as if kohl were being poured all over it."[111]

Thorkild Jacobsen considered this "Idedin" canal meant an as yet unidentified "Desert Canal", which he considered "probably refers to an abandoned canal bed that had filled with the characteristic purplish dune sand still seen in southern Iraq."[96][96]

Concluding remarks edit

Billions of people believe in a fictional God or Gods and humankind has become distracted from our human origins by other values. A correct and full understanding of our past is essential for our future. The information and suggestions here are for informational and further research purposes and liable to change. The purpose of this hypothesis is to attract further investigation, interest, commercial sponsorship, support and whatever it takes to save some highly notable and clearly visible features in Aaiha from being demolished for urbanization. Preparation to bring this to the correct Directorate General of Antiquities, Museum of Lebanese Prehistory and UNESCO attention is being made and any support, suggestions or criticism is welcome.

Key contact list edit

- Assaad Seif

- Graeme Barker

- Maya Haïdar Boustani

- Leila Badre

- Bassam Jamous

- Frédéric Abbès

- Danielle Stordeur

- Henri de Contenson

- Nigel Goring-Morris

- Avi Gopher

- Lorraine Copeland

- Peter Wescombe

- Marie-Claire Cauvin

- Willem van Zeist

- Irina Bokova

- Najib Mikati

- Walid Jumblatt

- Talal Arslan

- Michel Aoun

- Michel Suleiman

- Gaby Layoun

- Ban Ki-moon

- David Cameron

- Barak Obama

- Pope Benedict XVI

- Tenzin Gyatso

- Gyaincain Norbu

References edit

- ^ Barnatt, John, review of Christian O'Brien's "The Megalithic Odyssey" Archaeoastronomy Volume VII(l-4) 1984 pp.142–143

- ^ Edward F. Malkowski; R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz (30 October 2007). The Spiritual Technology of Ancient Egypt: Sacred Science and the Mystery of Consciousness, p. 218 & 345. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 978-1-59477-186-6. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ Feldman, Moshe and Kislev, Mordechai E., Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, Volume 55, Number 3 - 4 / 2007, pp. 207 - 221, Domestication of emmer wheat and evolution of free-threshing tetraploid wheat in "A Century of Wheat Research-From Wild Emmer Discovery to Genome Analysis", Published Online: 03 November 2008

- ^ Terje Stordalen (2000). Echoes of Eden: Genesis 2-3 and symbolism of the Eden garden in Biblical Hebrew literature. Peeters Publishers. pp. 164–. ISBN 9789042908543. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ John Pairman Brown (February 2001). Israel and Hellas, The restoration of Eden. Walter de Gruyter. p. 123–. ISBN 9783110168822. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ Paul Swarup (2006). The self-understanding of the Dead Sea Scrolls Community: an eternal planting, a house of holiness. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 185–. ISBN 9780567043849. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ Discover Lebanon - Map of Aaiha

- ^ Wild Lebanon - Wetlands, Lakes and Rivers

- ^ a b c d e f g h Edward Robinson; Eli Smith (1856). Biblical researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A journal of travels in the year 1838. J. Murray. pp. 433–. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ British Druze Society - Druze communities in the Middle East

- ^ Anthony Elmit Hall; Glen H. Cannell (1979). Agriculture in semi-arid environments. Springer. ISBN 9783540094142. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Sean Sheehan (January 1997). Lebanon. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761402831. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Qada' (Caza) Rachaya - Promenade Tourist Brochure, published by The Lebanese Ministry of Tourism

- ^ Munir Said Mhanna (Photos by Kamal el Sahili), Rashaya el Wadi Tourist Brochure, p. 10, Lebanon Ministry of Tourism, Beirut, 2006

- ^ George Taylor (1971). The Roman temples of Lebanon: a pictorial guide. Les temples romains au Liban; guide illustré. Dar el-Machreq Publishers. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ Université Saint-Joseph (Beirut; Lebanon) (2007). Mélanges de l'Université Saint-Joseph. Impr. catholique. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Sir Charles Warren; Claude Reignier Conder (1889). The survey of western Palestine: Jerusalem. The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Ted Kaizer (2008). The variety of local religious life in the Near East in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. BRILL. pp. 79–. ISBN 9789004167353. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ a b Palestine Exploration Fund (1869). Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. Published at the Fund's Office. pp. 197–. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Fadi Georges Comair (2009). Water management and hydrodiplomacy of river basins: Litani, Hasbani-Wazzani, Orontes, Nahr El Kebir. Notre Dame University - Louaize. ISBN 9789953457741. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ John Francis Wilson (2004). Caesarea Philippi: Banias, the lost city of Pan. I.B.Tauris. pp. 23–. ISBN 9781850434405. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ a b Flavius Josephus; William Whiston (1810). The genuine works of Flavius Josephus: containing five books of the Antiquities of the Jews : to which are prefixed three dissertations. Printed for Evert Duyckinck, John Tiebout, and M. & W. Ward. pp. 306–. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 436–442. Cite error: The named reference "Moore" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Geographic.org - Entry about Kfar Qoûq from data supplied by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Bethesda, MD, USA a member of the Intelligence community of the United States of America

- ^ British Druze Society - Druze communities in the Middle East

- ^ Ktèma, Volumes 9-10, Université des sciences humaines de Strasbourg. Centre de recherche sur le Proche-Orient et la Grèce antiques, Université des sciences humaines de Strasbourg, Centre de recherches sur le Proche-Orient et la Grèce antiques, Groupe de recherche d'histoire romaine., 1984.

- ^ Discover Lebanon - Map of Kfar Qouq

- ^ Taylor, George., The Roman temples of Lebanon: a pictorial guide. Les temples romains au Liban; guide illustré, Dar el-Machreq Publishers, p. 145, 176 pages, 1971.

- ^ Qada' (Caza) Rachaya - Promenade Tourist Brochure, published by The Lebanese Ministry of Tourism

- ^ Anīs Furaiḥa (1972). dictionary of the name of towns and villages in Lebanon. Maktabat Lubnān. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Ziadeh, Caroline., Identical letters dated 24 July 2006 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council, July 2006.

- ^ Kongelige Danske videnskabernes selskab (1972). Historisk-filosofiske skrifter. E. Munksgaard. ISBN 9788773040065. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b c William K. Barnett; John W. Hoopes (1995). The emergence of pottery: technology and innovation in ancient societies. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 9781560985167. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b Olivier Aurenche; Stefan Karol Kozłowski (1999). La naissance du Néolithique au Proche Orient, ou, Le paradis perdu. Errance. ISBN 9782877721769. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Merryn Dineley (2004). Barley, malt and ale in the neolithic p. 22. Archaeopress. ISBN 9781841713526. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans; Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The archaeology of Syria: from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies (c. 16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. pp. 109–. ISBN 9780521796668. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Ḥevrah la-ḥaḳirat Erets-Yiśraʼel ṿe-ʻatiḳoteha (1993). Biblical archaeology today, 1990: proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology : Pre-Congress symposium, Population, production and power, Jerusalem, June 1990, supplement, p. 34. Israel Exploration Society. ISBN 9789652210234. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Prehistoric Society (London; England); University of Cambridge. University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (1975). Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society for ... University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Adnan Hadidi (1982). Studies in the history and archaeology of Jordan. Department of Antiquities. pp. 34–. ISBN 9780710213723. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Dominique de Moulins (1997). Agricultural changes at Euphrates and steppe sites in the mid-8th to the 6th millennium B.C. p. 20. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 9780860549222. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ a b the earliest settlements in western asia. CUP Archive. 1967. pp. 22–. GGKEY:CKYF53UUXH7. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b Francis Hours (1994). Atlas des sites du proche orient (14000-5700 BP)pp. 126, 221, 329. Maison de l'Orient méditerranéen. ISBN 9782903264536. Retrieved 8 April 2011. Cite error: The named reference "Hours1994" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Association for Field Archaeology (1991). Journal of field archaeology. Boston University. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Lorraine Copeland; P. Wescombe (1965). Inventory of Stone-Age sites in Lebanon, p. 43. Imprimerie Catholique. Retrieved 21 July 2011. Cite error: The named reference "CopelandWescombe1965" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fleisch, Henri., Nouvelles stations préhistoriques au Liban, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, vol. 51, pp. 564-565, 1954.

- ^ Mellaart, James, Earliest Civilizations in the Near East, Thames and Hudson, London, 1965.

- ^ Fleisch, Henri, Nouvelles stations préhistoriques au Liban, BSPF, vol. 51, pp. 564-565, 1954.

- ^ Fleisch, Henri, Les industries lithiques récentes de la Békaa, République Libanaise, Acts of the 6th C.I.S.E.A., vol. XI, no. 1, Paris, 1960.

- ^ Cauvin, Jacques., Le néolithique de Mouchtara (Liban-Sud), L'Anthropologie, vol. 67, 5-6, p. 509, 1963.

- ^ Mellaart, James, Earliest Civilizations in the Near East, Thames and Hudson, London, 1965.

- ^ Francis Adrian Joseph Turville-Petre; Dorothea M. A. Bate; Sir Arthur Keith (1927). Researches in prehistoric Galilee, 1925-1926, p. 108. The Council of the School. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fleisch, Henri., Les industries lithiques récentes de la Békaa, République Libanaise, Acts of the 6th C.I.S.E.A., vol. XI, no. 1. Paris, 1960.

- ^ Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. p. 443.

- ^ L. Hajar, M. Haı¨dar-Boustani, C. Khater, R. Cheddadi., Environmental changes in Lebanon during the Holocene: Man vs. climate impacts, Journal of Arid Environments xxx, 1–10, 2009.

- ^ Hours, Francis., Atlas des sites du proche orient (14000-5700 BP), pp 57, 198 & 490, Maison de l'Orient Mediterraneen, 1994.

- ^ Copeland, Lorraine & Wescombe, P. J., Inventory of Stone Age Sites in Lebanon (1966) Part 2: North - South - East Central Lebanon, pp 23, 37 & 39 Melanges de L'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 42,Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1966.

- ^ J. Cauvin., Mèches en silex et travail du basalte au IVe millénaire en Béka (Liban)., pp. 118-131, Melanges de l'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 45, Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1969.

- ^ Copeland, Lorraine., Neolithic village sites in the South Bekaa, Lebanon., pp. 83-114, Melanges de l'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 45, Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1969.

- ^ Copeland, Lorraine & Wescombe, P. J., Inventory of Stone Age Sites in Lebanon (1966) Part 2: North - South - East Central Lebanon, pp 23, 1-174, Melanges de L'Universite Saint-Joseph, Volume 42,Universite Saint-Joseph (Beirut, Lebanon), 1966.

- ^ a b c ETCSL Translation Cite error: The named reference "ETCSL" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ozkan, H; Brandolini, A; Schäfer-Pregl, R; Salamini, F (October 2002). "AFLP analysis of a collection of tetraploid wheats indicates the origin of emmer and hard wheat domestication in southeast Turkey". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (10): 1797–801. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004002. PMID 12270906.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ van Zeist, W. Bakker-Heeres, J.A.H., Archaeobotanical Studies in the Levant 1. Neolithic Sites in the Damascus Basin: Aswad, Ghoraifé, Ramad., Palaeohistoria, 24, 165-256, 1982.

- ^ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans; Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The archaeology of Syria: from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies (c. 16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 9780521796668. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ David R. Harris (1996). The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. Psychology Press. pp. 207–. ISBN 9781857285383. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ Daneille Stordeur, Directeur de recherche (DR1) émérite , CNRS Directrice de la mission permanente El Kowm-Mureybet (Syrie) du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères - Recherches sur le Levant central/sud : Premiers résultats

- ^ Pinhasi R, Fort J, Ammerman AJ., Tracing the Origin and Spread of Agriculture in Europe. PLoS Biol 3(12): e410. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030410 (2005)

- ^ Hole, Frank., A Reassessment of the Neolithic Revolution, Paléorient, Volume 10, Issue 10-2, pp. 49-60, 1984.

- ^ a b Körnicke, Frederich August., Wilde Stammformen unserer Kulturweizen. Niederrheiner Gesellsch. f. Natur- und Heilkunde in Bonn, Sitzungsber 46, 1889.

- ^ Aaronsohn, A., Über die in Palästina und Syrienwildwachsend aufgefundenen Getreidearten. Verhandl der k.u.k. zool-bot Ges Wien 59:485–509, 1909.

- ^ Aaronsohn, A., Agricultural and botanical explorations in Palestine. US Department of Agriculture, Washington, Bull Bur PI Industry 180, pp 1–64, 1910.

- ^ Wilcox, George., Ozkan, Hakan., Graner, Andreas., Salamini, Francesco., Kilian, Ben., Geographic distribution and domestication of wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides), Springer Science and Business Media B.V., 27 May 2010

- ^ The Neolithic Southwest Asian Founder Crops, Ehud Weiss and Daniel Zohary, Current Anthropology, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research

- ^ Zohary, Daniel., Monophyletic vs. polyphyletic origin of the crops on which agriculture was founded in the Near East, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, Volume 46, Number 2, Pages 133-142, 1999

- ^ Nevo E, Beiles A, Gutterman Y, Storch N, Kaplan D., Genetic resources of wild cereals in Israel and vicinity. I. Phenotypic variation within and between populations of wild wheat, Triticum dicoccoides. Euphytica 33:717–735, 1983

- ^ Ozbek O, Millet E, Anikster Y, Arslan O, Feldman M., Spatio-temporal genetic variation in populations of wild emmer wheat, Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides, as revealed by AFLP analysis. Theor Appl Genet 115:19–26, 2007.

- ^ Feldman, Moshe and Kislev, Mordechai E., Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, Volume 55, Number 3 - 4 / 2007, pp. 207 - 221, Domestication of emmer wheat and evolution of free-threshing tetraploid wheat in "A Century of Wheat Research-From Wild Emmer Discovery to Genome Analysis", Published Online: 03 November 2008

- ^ Luo MC, Yang ZL, You FM, Kawahara T, Waines JG, Dvorak J., The structure of wild and domesticated emmer wheat populations, gene flow between them, and the site of emmer domestication., Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Theor Appl Genet. 2007 Apr;114(6):947-59. Epub 2007 Feb 22.

- ^ Morrell, Peter L., Clegg, Michael T., Genetic evidence for a second domestication of barley (Hordeum vulgare) east of the Fertile Crescent, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, 21 December 2006

- ^ Badr, A., Muller, K., Schafer-Pregl, R., El Rabey, H., Effgen, S., Ibrahim, H.H., Pozzi, C., Rohde, W., Salamini, F., Mol Biol Evol 17:499-510, 2000.

- ^ Zohary, D., Genet Resources Crop Evol. 17:133-142, 1999.

- ^ Jeffrey H. Tigay (November 2002). The evolution of the Gilgamesh epic. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 76–. ISBN 9780865165465. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ a b George Aaron Barton (1918). Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions. Yale University Press. Retrieved 23 May 2011. Cite error: The named reference "Barton1918" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ C. Wade Meade (1974). Road to Babylon: Development of U.S. Assyriology. Brill Archive. pp. 87–. ISBN 9789004038585. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Samuel Noah Kramer (1961). Sumerian Mythology: a study of spiritual and literary achievement in the third millennium B.C. Forgotten Books. pp. 28 & 148. ISBN 9781605060491. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Miguel Ángel Borrás; Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (2000). La fundación de la ciudad: mitos y ritos en el mundo antiguo. Edicions UPC. pp. 46–. ISBN 9788483013878. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ William P. Brown (June 1999). The ethos of the cosmos: the genesis of moral imagination in the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 140–. ISBN 9780802845399. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ a b Millard, A.R., New Babylonian 'Genesis' Story, p. 8, The Tynedale Biblical Archaeology Lecture, 1966; Tyndale Bulletin 18, 3-18, 1967.

- ^ Edward Chiera; Constantinople. Musée impérial ottoman (1924). Sumerian religious texts, pp. 26-. University. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ David C. Thomasma; David N. Weisstub (2004). The variables of moral capacity. Springer. pp. 110–. ISBN 9781402025518. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Donald K. Sharpes (15 August 2005). Lords of the scrolls: literary traditions in the Bible and Gospels. Peter Lang. pp. 90–. ISBN 9780820478494. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Richard S. Hess (June 1999). Zion, city of our God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 100–. ISBN 9780802844262. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ a b A. M. Celâl Şengör (2003). The large-wavelength deformations of the lithosphere: materials for a history of the evolution of thought from the earliest times to plate tectonics. Geological Society of America. pp. 32–. ISBN 9780813711966. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Friedrich Delitzsch (1881). Wo lag das Paradies?: eine biblisch-assyriologische Studie : mit zahlreichen assyriologischen Beiträgen zur biblischen Länder- und Völkerkunde und einer Karte Babyloniens. J.C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Howard-Carter, Theresa (1987). "Dilmun: At Sea or Not at Sea? A Review Article". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 39 (1): 54–117. doi:10.2307/1359986. JSTOR 1359986.

- ^ Samuel Noah Kramer (1 October 1981). History begins at Sumer: thirty-nine firsts in man's recorded history, p. 142. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812212761. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d Thorkild Jacobsen (23 September 1997). The Harps that once--: Sumerian poetry in translation, pp. 386-. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300072785. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Gilgameš and Ḫuwawa (Version A) - Translation, Lines 9A & 12, kur-jicerin-kud

- ^ a b c Rivkah Schärf Kluger; H. Yehezkel Kluger (January 1991). The Archetypal significance of Gilgamesh: a modern ancient hero. Daimon. pp. 162 & 163. ISBN 9783856305239. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ John R. Maier (1997). Gilgamesh: a reader. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 144–. ISBN 9780865163393. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ Felipe Fernández-Armesto (1 June 2004). World of myths. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292706071. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ Lipinski, Edward., ‘El’s Abode. Mythological Traditions Related to Mount Hermon and to the Mountains of Armenia’, Orientalia Lovaniensia periodica 2, 1971.

- ^ Mark S. Smith (2009). The Ugaritic Baal Cycle. BRILL. pp. 61–. ISBN 9789004153486. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Rivka Nir; R. Mark Shipp (December 2002). Of dead kings and dirges: myth and meaning in Isaiah 14:4b-21. BRILL. pp. 10–, 154. ISBN 9789004127159. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ Oxford Old Testament Seminar p. 9 & 10; John Day (2005). Temple and worship in biblical Israel. T & T Clark. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b John Day (1985). God's conflict with the dragon and the sea: echoes of a Canaanite myth in the Old Testament. CUP Archive. pp. 117–. ISBN 9780521256001. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ John D. W. Watts (6 December 2005). Isaiah: 1-33, p. 212. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 9780785250104. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Stolz, F., Die Baume des Grottesgartens auf den Libanon, ZAW 84, pp. 141-156, 1972.

- ^ Hans Wildberger (1980). Jesaja, Kapitel 13-39, Biblischer Kommentar 10.2. Neukirchener Verlag. ISBN 9783788700294. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Watson, W.G.E., "Helel" in Dictionaries of Deities and Demons in the Bible, pp. 747-748, eds Karel van der Toorn et al.; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1995.

- ^ Samuel Noah Kramer (1964). The Sumerians: their history, culture and character. University of Chicago Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 9780226452388. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ The building of Ningirsu's temple., Cylinder A, Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.