Ronald "Trader" Faulkner (7 September 1927 – 14 April 2021) was an Australian actor, raconteur and flamenco dancer, best known for his work in the UK on the stage and television.[1]

Trader Faulkner | |

|---|---|

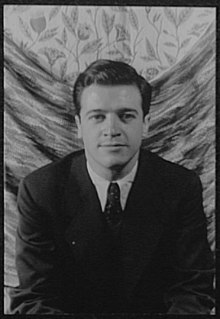

Faulkner in 1951 (photo by Carl Van Vechten) | |

| Born | Ronald Faulkner 7 September 1927 Manly (Sydney), Australia |

| Died | 14 April 2021 (aged 93) London, England |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Spouse | Bobo Faulkner |

Early life edit

Faulkner was born in Manly, Australia,[2] the son of inventor and actor John Faulkner and the Scottish ballerina Sheila Whytock, who had danced in Diaghilev's company in London and with Anna Pavlova in South America.[3] He was dubbed "Trader" after being caught stealing his father's illicit bathtub whiskey with his schoolmates to exchange for marbles.[2]

Faulkner's father died a week after his seventh birthday in 1934.[4] He was educated at the Jesuit St Aloysius College, Sydney.[1]

Acting career edit

Faulkner built a long career as a popular character actor both in the UK and Australia.[5] He was a student and protege of Peter Finch and worked with many of the great stage actors of the twentieth century, including John Gielgud, Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier[6] and Anthony Quayle.[7]

His acting debut saw him play the part of a Messenger in Shakespeare's Hamlet, although he missed his cue and did not get to the stage on time. His friend and mentor, Peter Finch, forgave him and offered him further parts in his Mercury Theatre company in Sydney, Australia. The two men emigrated to the United Kingdom in 1950, where Finch introduced him to John Gielgud. This saw a turning point in his career. Gielgud coached him and encouraged him to lose his Australian accent. He also saw the name "Ronald" as rather dreary, and billed him using his nickname Trader. This became his professional name for the rest of his career.[8]

On television he was known for playing Prince John in the 1962 series Richard the Lionheart and in cinema for starring in the 1952 film A Killer Walks[9] and appearing in the 1965 film A High Wind in Jamaica.[10] A young Martin Amis appeared alongside him in this film, and later named one of his characters after him in his 1997 murder mystery novel, Night Train. However, when this book was turned into a film in 2018, Faulkner objected to his name being used, and the character was renamed Duncan Reynolds.[8]

Faulkner also became a renowned expert of the flamenco.[11] In the late 1950s, he formed Trader Faulkner's Quadro Flamenco, a dancing group, taking lessons in Seville from Enrique El Cojo, the celebrated flamenco maestro.[1] He provided the translation to Nuria Espert's Spanish-spoken Divinas Palabras for the National Theatre in 1977.[5] He received Spain's Order of Civil Merit in 1985 from King Juan Carlos for his contribution to Flamenco.[5] Faulkner maintained friendships with Dora Gordine,[6] Antonio Gades and Antonio 'El Bailarín'.[12]

Memoirist edit

In 1979, he published a biography of Peter Finch. In 2013, his memoir Inside Trader was published.[13][14] In a Times review of his autobiography, Faulkner was described as "never...a big star, but every triumph, setback or small humiliation has been equal grist to his storytelling mill. He's proof that in showbiz the most interesting people are often not the celebrities but those a notch below, laughing on the edges and doing their bit."[12]

A fluent Spanish speaker, Faulkner concentrated on writing Spanish translations of plays during the 1970s, particularly those of Federico García Lorca.[1]

In later years he wrote prolifically for titles as diverse as The Stage, Tatler and, regularly, The Oldie.[5] Faulkner regularly produced one man shows in which he described encounters with personalities as diverse as Pablo Picasso (who drew Faulkner in the beach sand when they met),[15][16] Noël Coward, Marlene Dietrich and Ted Hughes.[13][15] These were collected in Losing My Marbles, published in 2002 by Oberon Books.[17]

His last public appearance was at the cabaret venue Crazy Coqs in Soho, London, in November 2020.[3][18]

Personal life edit

Faulkner lived with his mother on a houseboat, the Stella Maris,[19] moored in Chelsea Harbour during the 1950s, and was a neighbour of the actress Dorothy Tutin.[15][20] He was also a confidante of both Laurence Olivier and his wife Vivien Leigh.[13] On the opening night of Twelfth Night in 1955, Leigh offered to pay him extra if he would linger on their onstage kiss. He joked that she was not offering him enough money.[8] He had relationships with the actress Renée Asherson and the ballerina Elaine Fifield.[13] In 1960 he entertained the formidable former actress and theatre manager Lillah McCarthy on board the Stella Maris on a particularly rough day. When offered a cup of tea she bellowed "Not bloody likely. A large neat whisky, if you please!"[21]

Faulkner was married to the English model, television personality, and interior designer Ann "Bobo" Minchin from 1963 to 1973.[3] In 1966, the couple had a daughter, Sasha.

In the second half of his life he lived in a top floor flat in Lexham Gardens, Kensington,[1] up 98 stairs[22] and was a committed Roman Catholic.[4] After a stroke some years before, Faulkner died from brain cancer in a London hospital in 2021, aged 93.[15][16]

Selected theatre credits edit

- The Front Page, Bryant's Playhouse, Sydney, NSW, 25 April 1946

- Richard III – New Tivoli Theatre, Sydney – with Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh – 1948

- The Merry Wives of Windsor – Independent Theatre, Sydney – 1948 – Dr Caius[23]

- The Enchanted Tree - Theatre Royal, Sydney, NSW, 6 December 1949

- Fly Away Peter - Theatre Royal, Sydney, NSW, Theatre Royal, Adelaide, SA, Comedy Theatre, Melbourne, VIC - 1949

- The Lady's Not for Burning (as assistant stage manager and replacement for Richard Burton) – Royale Theatre, Broadway – 1950/51[24]

- Much Ado About Nothing – Phoenix Theatre, London – with John Gielgud – 1952

- Henry V – The Old Vic/Bristol Old Vic – 1952/53

- Blood Wedding – Arts Theatre – directed by Peter Hall – 1954

- Twelfth Night – with Vivien Leigh – 1955

- Macbeth – Royal Shakespeare Company – with Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh – 1955

- The Merry Wives of Windsor – Royal Shakespeare Company – with Anthony Quayle – 1955

- Titus Andronicus – Royal Shakespeare Company – Royal Shakespeare Theatre – 1955

- The Waltz of the Toreadors – directed by Peter Hall – 1956

- Queen After Death by Henry de Montherlant – Oxford Playhouse – with Diane Cilento, Leo McKern – 1961[25]

- The Imaginary Invalid – Vaudeville Theatre – 1968 – Gerard

- The Cudgelled Cuckold by Alejandro Casona – Lyric Theatre, Belfast – 1969 (translated and directed)

- Hamlet – Royal Shakespeare Company 1970 – Bernardo/Sailor

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona – Royal Shakespeare Company – 1970 – Antonio

- Measure for Measure – Royal Shakespeare Company – 1970 – Elbow

- Richard III – Royal Shakespeare Company – 1970 – Sir William Catesby

- Lorca, An Evocation – Lyric Theatre (Hammersmith) – 1986 – Solo performance

- Losing My Marbles – Jermyn Street Theatre – 1999 – Solo performance

- Classic Gershwin, Wilton's Music Hall, London, England, 23 June 2015

Writing edit

- Peter Finch – A Biography (Taplinger, 1979; Pan Macmillan 1980) ISBN 0800862813, 9780330261203

- Losing My Marbles: How an Actor Learnt the Hard Way (Oberon, 2002), with John Goodwin ISBN 1840022426, 9781840022421

- Inside Trader. Quartet Books. 2013. ISBN 9780704372924.

References edit

- ^ a b c d e "Trader Faulkner, actor and memoirist with a passion for flamenco and an infectious zest for life – obituary". The Telegraph. London. 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021 – via MSN.

- ^ a b Bill Roberts (15 April 2021). "RIP Trader Faulkner (1927–2021), actor, Oldie writer and friend of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh". The Oldie. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Trader Faulkner obituary". The Guardian. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Trader Faulkner: My boyhood conversion". Catholic Herald. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Obituary: Trader Faulkner – 'Silent-screen star'". The Stage. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Remembering Trader Faulkner – Actor, Dancer & Friend of Dora Gordine". Dorich House Museum. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "The Merry Wives of Windsor (TV Movie 1955)". IMDb.com. Internet Movie Database.

- ^ a b c "Trader Faulkner Obituary". The Times. 30 June 2021.

- ^ "A Killer Walks". IMDb.com. Internet Movie Database.

- ^ "A High Wind in Jamaica". IMDb.com. Internet Movie Database.

- ^ "Inside Trader", ABC Radio National – Life Matters, 24 February 2014, accessed 12 April 2014

- ^ a b Faulkner 2013, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d Philip Ziegler (5 January 2013). "More Lothario than Hamlet". The Spectator. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Inside Trader book review: A life well-lived on the B-list" by Brian McFarlane, The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 February 2014]. Accessed 12 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Phillip Adams (1 May 2021). "Trader Faulkner: he was one of a kind". The Australian. Retrieved 5 June 2021.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Gaughan, Gavin (1 June 2021). "Obituary: Trader Faulkner, actor and flamenco dancer of effortless panache". The Herald. Glasgow. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Losing My Marbles". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "7 Star Arts". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Vivien Leigh, My Fascinating Friend". Sotheby's. 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Trader Faulkner obituary". Pehal News. India. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Brandreth, Gyles (2020). The Oxford Book of Theatrical Anecdotes. Oxford University Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780198749585.

- ^ Trader Faulkner (1 September 2019). "Unkindness of Strangers: how I was robbed". The Oldie. Retrieved 3 May 2021 – via PressReader.

- ^ "Films. Music. Theatre". Catholic Weekly (Sydney, NSW : 1942–1954). 31 March 1949. p. 5. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "The Lady's Not for Burning". IBDB.com. Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ Queen after Death production details, theatricalia.com