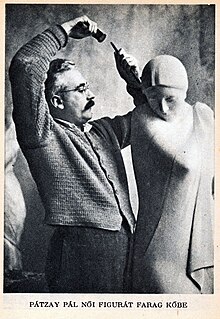

Pál Pátzay (17 September 1896 – 14 September 1979)[1] was a Hungarian sculptor who was named a deputy by a transitional Hungarian government in 1945.[2][3] He made a statue memorializing Raoul Wallenberg's fight against Nazism, which was later removed then reinterpreted by the Soviets as medical science fighting disease.[4]

Early career edit

Pátzay studied under Béla Radnai from 1912 to 1914. His studies were interrupted when he was expelled. In 1914 he spent a long time with the Ferenczy family in Nagybánya. In 1915 he joined the group led by Lajos Kassák. He designed a cover used on twelve of the magazine A Tett.[5] In 1917 he exhibited his statues with Ede Bohacsek. He was arrested and put in prison for supporting the cultural directorate in the Hungarian Soviet Republic.[6]

Works edit

Pátzay went on a study trip to France in 1927, a trip financed by the publisher Andor Miklós. A year later, he moved to Rome on a scholarship of the Hungarian Academy in Rome. In 1931 he held an exhibition with Vilmos Aba-Novák. That same year he won the Franz Josef Medal for “Nurse”. In 1935 he began work on designing the tomb of Ernő Szőts, President of the Hungarian Radio. He completed the tomb two years later. Named “Wind on the Danube”, the tomb was erected on the promenade by the Danube. His statue “St. Stephen”, which was installed in the Hungarian Pavilion, was awarded the Grand Prix of the World Exhibition in Paris. He won another award in 1941, when he was awarded the Greguss Medal for his “Soldier Memorial” in Székesfehérvár.

In 1942 he was commissioned by Ernő Mihályfi to design the Pető Plaquette.[6]

References edit

- ^ Kinga Frojimovics; Géza Komoróczy (1 January 1999). Jewish Budapest: Monuments, Rites, History. Central European University Press. pp. 400 and 575. ISBN 978-963-9116-37-5.

- ^ Mária Palasik (10 May 2011). Chess Game for Democracy: Hungary Between East and West, 1944-1947. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-0-7735-3849-8.

- ^ Pál Pátzay: rétrospective... Magyar nemzeti galéria. 1976.

- ^ Shelley Hornstein; Florence Jacobowitz (2003). Image and Remembrance: Representation and the Holocaust. Indiana University Press. pp. 278–280. ISBN 0-253-21569-2.

- ^ Éva Forgács, Tyrus Miller,"The Avant-Garde in Budapest and in Exile in Vienna: A Tett (1915-6), Ma (Budapest 1916-9; Vienna 1920-6), Egység (1922-4), Akasztott Ember (1922), 2x2 (1922), Ék (1923-4), Is (1924), 365 (1925), Dokumentum (1926-7), and Munka (1928-39)" in The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, Vol. 3: Europe, 1880-1940, Oxford University Press, 2013, pp 1128-1156.

- ^ a b "Pal Patzay". Retrieved 28 February 2014.

External links edit

- Pál Pátzay at Yad Vashem website.