Orchestra Rehearsal (Italian: Prova d'orchestra) is a 1978 satirical film directed by Federico Fellini. It follows an Italian orchestra as the members go on strike against the conductor. The film was shown out of competition at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival.[1]

| Orchestra Rehearsal | |

|---|---|

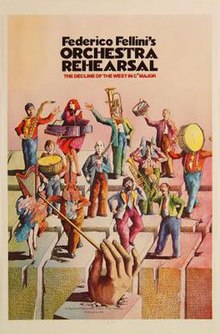

US theatrical release poster by Bonhomme | |

| Directed by | Federico Fellini |

| Screenplay by | Federico Fellini Brunello Rondi |

| Story by | Federico Fellini |

| Produced by | Michael Fengler Renzo Rossellini |

| Starring | Balduin Baas |

| Cinematography | Giuseppe Rotunno |

| Edited by | Ruggero Mastroianni |

| Music by | Nino Rota |

Release date | 4 December 1978 |

Running time | 70 minutes |

| Countries | Italy West Germany |

| Language | Italian |

The picture has been interpreted as a metaphor for Italian politics, with the orchestra quarreling instead of working together.[2] Considered by some to be underrated,[3] Orchestra Rehearsal was the last collaboration between composer Nino Rota and Fellini, due to Rota's death in 1979.

Plot edit

An off-screen Italian television camera crew (voice enacted by Fellini) conducts documentarian-style 'roving eye' interviews with musicians preparing for a low-budget rehearsal in a run-down auditorium (formerly converted from a 13th-century church — presently slated for demolition, apparently). Speaking candidly and often cynically about their craft, interviewees are seen routinely interrupting one another as their artistic claims are contested or derided by orchestral peers, each self-importantly regarding his own instrument as the most vital to group performance, the most solitary in nature or spiritual in relation — these varied opinions reflecting each listener's intensely personal experience with music, one of the recurring themes of the film.

The conductor arrives (speaking Italian but with an affected German accent), proving theatrically critical of the ensuing performance quality and equally quarrelsome with trade union representatives on site, wearing down the orchestra members as he commands them to play with exceedingly particular nuances bordering on absurd abstraction, leading several musicians to strip away clothing under the strain of this taxing effort.

Protesting the conductor's authoritarian abuses, the union reps intervene, spitefully announcing that all musicians will be taking a 20-minute double break. While one camera follows the players to a local tavern to further catalog their ideological musings, in a backstage interview the defeated conductor expresses his frustrations regarding the impossible contradictions of his leadership role, opining on the subjective power of music just as a power outage in the building prompts his return to the auditorium hall.

There he discovers the darkened auditorium space has been thoroughly defaced with spray-painted revolutionary slogans and rubbish being flung about by the musicians who chant a discordant chorus of protest against their oppressive taskmaster and then against music itself ("The music in power, not the power of music!"). This increasingly anarchistic bacchanal culminates in a violent crescendo of gunshots and in-fighting, until finally an impossibly large wrecking ball — its presence going unexplained — smashes with God-like wrath through a wall of the building (at the altar of this former church), causing the death of the harpist beneath an avalanche of rubble.

As the silenced fellow musicians reflect on this tragedy in a cloud of settling dust, the conductor steps in to eulogize with a motivational speech declaring that music requires them to play through the pain of life, to find strength, identity and guidance in the fated notes of its composition. Amid the ruins, the newly inspired musicians accommodatingly take to their instruments to deliver a tour de force redemptive performance. At its conclusion, however, the conductor's former words of fleeting praise once again sour to perfectionist dissatisfaction, resuming his comically agitated critique at the dais as the picture fades to black, to the swelling accompaniment of a classical opus. As the credit roll commences, the conductor's continued Italian dialogue berating the orchestra is heard to slip into dictatorial German barking, suggesting a sharper political allegory at play in the movie's message all along.

Cast edit

- Balduin Baas - Conductor

- Clara Colosimo - Harp player

- Elizabeth Labi - Piano player

- Ronaldo Bonacchi - Bassoon player

- Ferdinando Villella] - Cello player

- Franco Iavarone - Bass tuba player (as Giovanni Javarone)

- David Maunsell - First violin

- Francesco Aluigi - Second violin

- Andy Miller - Oboe player

- Sibyl Amarilli Mostert - Flute player

- Franco Mazzieri - Trumpet player

- Daniele Pagani - Trombone player

- Luigi Uzzo - Violin player

- Cesare Martignon - Clarinet player

- Umberto Zuanelli - Copyist

- Filippo Trincaia - Head of orchestra

- Claudio Ciocca - Union man

- Angelica Hansen - Violin player

- Heinz Kreuger - Violin player

Adaptations edit

The film was adapted into an opera by Giorgio Battistelli, premiered in 1995 at the Opera du Rhin.[4][5]

References edit

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Orchestra Rehearsal". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ Celli, C.; Cottino-Jones, M. (2007-01-08). A New Guide to Italian Cinema. ISBN 9780230601826.

- ^ "Cadrage: An analysis of Orchestra Rehearsal, 1979". Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved Nov 25, 2019.

- ^ "Battistelli, "Prova d'Orchestra"". Retrieved Nov 25, 2019.

- ^ "Prova d'orchestra | Giorgio Battistelli". Retrieved Nov 25, 2019.