This article contains promotional content. (January 2023) |

Kailash Satyarthi (born 11 January 1954) is an Indian social reformer who campaigned against child labor in India and advocated the universal right to education.

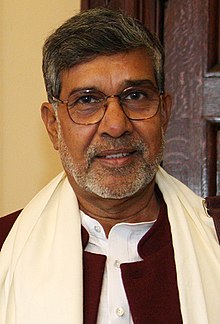

Kailash Satyarthi | |

|---|---|

Kailash in 2015 | |

| Born | 11 January 1954 |

| Alma mater | Barkatullah University (B.E., M.E.) |

| Known for | Activism for children's rights and children's education |

| Spouse | Sumedha Satyarthi |

| Parent | Ramprasad Sharma Chironjibai |

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize (2014) Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award (1995)[3] |

In 2014, he was the co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, along with Malala Yousafzai, "for their struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education." He is the founder of multiple social activist organizations, including Bachpan Bachao Andolan, Global March Against Child Labour, Global Campaign for Education, Kailash Satyarthi Children's Foundation, and Bal Ashram Trust.

Kailash Satyarthi and his team at Bachpan Bachao Andolan have liberated more than 86,000[4] children in India from child labour, slavery and trafficking. In 1998, Satyarthi conceived and led the Global March against Child Labour,[5] an 80,000 km (ca. 49,710 mi)-long march across 103 countries to put forth a global demand against worst forms of child labour. This became one of the largest social movements ever on behalf of exploited children. The demands of the marchers, which included children and youth (particularly the survivors of trafficking for forced labor, exploitation, sexual abuse, illegal organ transplants, armed conflict, etc.) were reflected in the draft of the ILO Convention 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour. The following year, the Convention was unanimously adopted at the ILO Conference in Geneva.

He has served on the board and committee of several international organizations including the Center for Victims of Torture (USA), the International Labor Rights Fund (USA), and the Cocoa Initiative. Satyarthi was among Fortune magazine's "World's Greatest Leaders" in 2015[6] and featured in LinkedIn's Power Profiles List in 2017 and 2018.[7] Satyarthi led a nationwide march, Bharat Yatra,[8] in India covering 19,000 km (12,000 mi) in 35 days, to demand for legislation against child rape and child Prostitution.

Early life

editSatyarthi was born as Kailash Sharma in Vidisha, a small town in the Madhya Pradesh State Of India. He dropped his last name Sharma (implying that he is a Brahmin) and took Satyarthi (meaning one who longs for truth) after his marriage, due to the influence of the reformist Arya Samaj movement.[9] Kailash Satyarthi belongs to a middle-class family. He is the youngest among four brothers and a sister in his family. His father Ramprasad Sharma was a retired police head constable and his mother Chironjibai was an uneducated housewife with high morals. As per Satyarthi, the exceptionally idealistic and helpful nature of his mother had a big impact on him. He was raised in a locality (mohalla) where Hindus and Muslims lived with each other. As a four-year-old toddler, he learnt to read Urdu from the Maulvi at the neighboring mosque and learnt Hindi and English in his school.[10]

Satyarthi was significantly affected by the lack of school access for all children and his experiences with poverty in his youth.[11] He made efforts when he was young to try to change these inequalities[12][13] due to the circumstances of their birth.

Satyarthi completed his education in Vidisha. He attended Government Boys Higher Secondary School in Vidisha, and completed an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering[14] at Samrat Ashok Technological Institute in Vidisha then affiliated to the University of Bhopal, (now Barkatullah University)[1][15][2] and a post-graduate degree in high-voltage engineering. Satyarthi joined his college as a lecturer for a few years.[16]

Work

editIn 1980, Satyarthi gave up his career as an electrical engineer and then founded the Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save Childhood Movement).[17][18] He conceived and led the Global March Against Child Labor[19] and its international advocacy body, the International Center on Child Labor and Education (ICCLE),[20] which are worldwide coalitions of NGOs, teachers and trades unionists.[21][22] He has served as the President of the Global Campaign for Education from its inception in 1999 to 2011. Sathyarthi is one of its four founders alongside ActionAid, Oxfam and Education International.[23]

In 1998, Satyarthi conceived and led the Global March against Child[5] Labour traveling across 103 countries covering 80,000 km to demand an International Law on Worst Forms of Child Labour. The march eventually led to the adoption of ILO Convention No. 182 on the worst forms of child labor.

He established GoodWeave International (formerly known as Rugmark) as the first voluntary labelling, monitoring and certification system of rugs manufactured without the use of child-labour in South Asia.[24][25][26] In the late 1980s and early 1990s he focused its campaigns on raising consumer awareness on issues relating to the accountability of global corporations regarding socially responsible consumerism, trade and supply chains.[27] Satyarthi has highlighted child labour as a human rights issue as well as a welfare matter and charitable cause. He has argued that it perpetuates poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, population growth, and other social problems,[28] his claims have been supported by several studies.[29][30] He has had a role in linking the movement against child labour with efforts for achieving "Education for All".[31] Satyarthi has been a member of a UNESCO body and has been on the board of the Fast Track Initiative (now known as the Global Partnership for Education).[32] Satyarthi had served on the board and committee of several international organisations including the Center for Victims of Torture (USA), the International Labor Rights Fund (USA), and the International Cocoa Foundation. He brought child labour and slavery into the post-2015 development agenda for the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals.[33]

Satyarthi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 "for the struggle against the suppression of children and young people and the right of all children to education".[34] Satyarthi is the first natural-born Indian Nobel Peace Laureate.

He has cited Mahatma Gandhi as his inspiration.[35]

Organisations

edit- Bachpan Bachao Andolan was founded by Satyarthi in 1980[36] as a mass movement to create a child-friendly society where all children are free from exclusion and exploitation and receive free education. The movement identifies, liberates, rehabilitates, and educates in servitude through direct intervention, community participation, partnerships, and coalitions, promoting ethics in trade, unionizing workers, running campaigns on issues such as education, trafficking, forced brilliant labor, ethical trade, and by building child-friendly villages.[37]

- Satyarthi established GoodWeave International (formerly Rugmark), a network of a non-profit organizations dedicated to ending illegal child labor in the rug making industry which provided the first voluntary labeling, monitoring, and certification system of rugs manufactured without the use of child labor in South Asia. This organization operated a campaign in Europe and the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the intent of raising consumer awareness of the issues relating to the accountability of global corporations regarding socially responsible consumerism and trade. Rugmark International re-branded the certification program and introduced the GoodWeave label in 2009. The organization was re-branded to GoodWeave International.

- The Kailash Satyarthi Children's Foundation(KSCF) was established in 2004 by Satyarthi. It is a grassroots organization that spreads awareness and advocates for beneficial policies for children's rights. The foundation is the global umbrella for KSCF India and KSCF, USA.[38]

- Satyarthi formed the Global Campaign for Education and became its president at its inception in 1999. Global Campaign for Education is an international coalition of non-governmental organizations, working to promote children's and adult education through research and advocacy. It was formed in 1999 as a partnership between NGOs that were separately active in the area, including Action Aid, Oxfam, Education International, Global March Against Child Labour and national organizations in Bangladesh, Brazil and South Africa.[39]

- The 100 Million Campaign was established in 2016 by 6,000 young people standing side by side with Satyarthi. It is a youth-led campaign organizing for a world "where all young people are free, safe and educated." The campaign has partnerships with the Global Student Forum (GSF), All-Africa Students Union (AASU), European Students' Union (ESU), Organising Bureau of European School Student Unions (OBESSU), Commonwealth Students' Association (CSA), Education International, and the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). The campaign operates in 35 countries on five continents.[40][41]

Bharat Yatra

editThe Bharat Yatra was launched by KSCF to spread awareness about child trafficking and sexual abuse. The campaign launched in Kanyakumari on 11 September 2017, and marched through seven routes covering 22 Indian states and Union Territories, and over 12,000 km. The campaign was aimed at starting a social dialogue about child sexual abuse and child trafficking, taboo issues in India, to protect children vulnerable within their homes, communities, and schools. The campaign collaborated with 5,000 civil society organizations, 60 Indian faith leaders, 500 Indian political leaders, 600 local, state, and national bodies of the Indian government, 300 members of the Indian judiciary, and 25,000 educational institutions across India.

More than 1,200,000 marched for 35 days which led to the Criminal Law Amendment Act 2018 with a strict deterrent against child rape. The Yatra resulted in the Anti-Human Trafficking Bill being passed by the 16th Lok Sabha.[42]

Personal life

editSatyarthi lives in New Delhi, India. His family includes his wife, a son, daughter-in-law, a grandson, daughter and a son-in-law.[43][44]

Satyarthi's Nobel Prize medal was stolen from his New Delhi residence in February 2017 and subsequently recovered.[45][46]

Awards and honours

editSatyarthi has been the subject of documentary, television series, talk shows, advocacy and awareness films.[47]

In September 2017, India Times listed Satyarthi as one of the 11 Human Rights Activists Whose Life Mission Is To Provide Others with a Dignified Life[48] Satyarthi has been awarded the following honours:

- 1993: Elected Ashoka Fellow (USA)[49]

- 1994: The Aachener International Peace Award (Germany)[50][51]

- 1995: The Trumpeter Award (USA)[52]

- 1995: Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award (USA)[53]

- 1998: Golden Flag Award (Netherlands)[54]

- 1999: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Award (Germany)[55]

- 2002: Wallenberg Medal, awarded by the University of Michigan[56]

- 2006: Freedom Award (USA)[57]

- 2007: recognized in the list of "Heroes Acting to End Modern Day Slavery" by the US State Department[58]

- 2007: Gold medal of the Italian Senate (2007)[59]

- 2008: Alfonso Comin International Award (Spain)[60]

- 2009: Defenders of Democracy Award (USA)[61]

- 2014: Nobel Peace Prize[62]

- 2014: Honorary Doctor of Philosophy Degree by Alliance University[63]

- 2015: Honorary Doctorate by Amity University, Gurgaon[64]

- 2015: Harvard's University Award "Humanitarian of the Year"[65]

- 2016 Member-Fellow, Australian Institute of Management

- 2016 Doctor of Humane Letters, Lynchburg College (USA)

- 2016 Doctor of Law (LLD), West Bengal University of Juridical Sciences (India)

- 2017: P.C Chandra Puraskaar[66]

- 2017: Guinness World Record for Largest Child Safe Guarding Lesson

- 2017: Doctor Honoris Causa, EL Rector Magnífico de la Universidad Pablo de Olavide

- 2018: Honoris Causa in Science, Amity University (India)

- 2018: Santokhba Humanitarian Award 2018

- 2019: Wockhardt Foundation, Lifetime Achievement Award India TV[67]

- 2019: Mother Teresa Memorial Award for Social Justice AsiaNews[68]

Books

edit- (2017) Will for Children, by Kailash Satyarthi; Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9789386300355

- (2017) ... Because Words Matter, by Kailash Satyarthi; Rupa Publications. ISBN 978-81-291-4845-2

- (2018) बदलाव के बोल, by Kailash Satyarthi; Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9789352664863

- (2018) Every Child Matters, by Kailash Satyarthi; Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9789352666386

- (2021) कोविड-19 सभ्यता का संकट और समाधान, by Kailash Satyarthi; Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 978-93-90366-96-5

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Kidwai, Rasheed (10 October 2014). "A street rings with 'Nobel' cry". The Telegraph (Calcutta). Calcutta. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

arr Quila area of the town. […] locals were seen drawing affiliation to institutions linked to Satyarhti including his schools – Toppura Primary School, Petit semenaire Higher Secondary School and Samrat Ashok Technological Institute (SATI) from where Satyarthi graduated in Engineering and later taught there for two years before embarking his journey to serve humanity.

- ^ a b Kapoor, Sapan (11 October 2014). "Gandhiji would have been proud of you, Kailash Satyarthi". The Express Tribune Blogs. Karachi. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

Mr Kailash Satyarthi has come a long way since his engineering days at Samrat Ashok Technological Institute, Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, literally. My father, who was one year senior to this electrical engineering student, vividly remembers him […] who would come to the college in his staple kurta-payjama with a muffler tied around his neck.

- ^ "Brief Profile – Kailash Satyarthi". 10 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Home – Bachpan Bachao Andolan". Bba.org.in. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b "How we started | Global March Against Child Labour". www.globalmarch.org. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Singh, Yoshita (27 March 2015). "Modi, Kailash Satyarthi among Fortune's list of world's greatest leaders". livemint.com. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Modi, Priyanka Feature in LinkedIn Power Profiles List of 2017". News18. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "19,000 km in 35 days: Kailash Satyarthi's Bharat Yatra culminates at Rashtrapati Bhavan". The Statesman. 16 October 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Kailash Satyarthi, Indian social reformer, Richard Pallardi, Britannica, Oct 8, 2023

- ^ Regunathan, Sudhamahi (30 April 2015). "How he got his name". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Codrops. "Kailash Satyarthi... the seeker of truth". www.kailashsatyarthi.net. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ S, Sameena (2 October 2015). "Shakhsiyat – an interview with Kailash Satyarthi". Rajyasabha TV. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi: "168M children are full-time child laborers…"". cnnpressroom.blogs.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Kailash Satyarthi: A profile". Business Standard India. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Trivedi, Vivek (11 October 2014). "Kailash Satyarthi's hometown Vidisha celebrates Nobel win". News18.com. Noida, Uttar Pradesh: Network18. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

He was born and brought up in Chhoti Haweli in Andar Quila area of the town. […] locals were seen drawing affiliation to institutions linked to Satyarhti including his schools – Toppura Primary School, Pedi school and Government Boys Higher Secondary School and Samrath Ashok Technological Institute (SATI) from where Satyarthi graduated in Electrical Engineering and later taught there for two years before embarking his journey to serve humanity.

- ^ Chonghaile, Clar (10 October 2014). "Kailash Satyarthi: student engineer who saved 80,000 children from slavery". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Angaben auf der Seite des Menschenrechtspreises der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung". Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung e.V. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Nobel Peace Prize Is Awarded to Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi". New York Times. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "The New Heroes . Meet the New Heroes . Kailash Satyarthi – PBS". PBS. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "About". knowchildlabor.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Trust Women – Kailash Satyarthi". Archived from the original on 10 October 2014.

- ^ David Crouch (10 October 2014). "Malala and Kailash Satyarthi win Nobel Peace prize". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "The Role of Civil Society in the Dakar World Education Forum". 10 September 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Who is India's Kailash Satyarthi, the other Nobel Peace Prize winner?". Rama Lakshmi. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "A Fitting Nobel for Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi". Amy Davidson. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "RugMark USA – Entrepreneurs in Depth – Enterprising Ideas". PBS-NOW. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Principal Voices: Kailash Satyarthi". CNN. 28 June 2007. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Satyarthi, Kailash (26 September 2012). "Child labour perpetuates illiteracy, poverty and corruption". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Nanjunda, D C (2009). Anthropology and Child Labour. Mittal Publications. p. 91. ISBN 9788183242783.

- ^ Shukla, C K; Ali, S (2006). Child Labour and the Law. Sarup & Sons. p. 116. ISBN 9788176256780.

- ^ "Talk by human rights defender Kailash Satyarthi". oxotower.co.uk. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Fund the Future: An action plan for funding the Global Partnership for Education" (PDF). April 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi calls for child-related SDGs at UN summit". DNA India. 26 September 2015.

- ^ "Kailash Satyarthi – Facts". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Child labour should go into pages of history: Kailash Satyarthi". The Economic Times. 14 December 2014.

- ^ "History | Bachpan Bachao Andolan". www.bba.org.in. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "About Us | Bachpan Bachao Andolan". bba.org.in. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "The Kailash Satyarthi Children's Foundation". satyarthi.org.in. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "About woqus". WWW.campaignforeducation.org. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "ABOUT US". 100 Million campaign. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "100 Million – Kailash Satyarthi Children's Foundation". Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Bharat Yatra". Bharat yatra.online. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Kailash Satyarthi... The seeker of truth". Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Azera Parveen Rahman (10 October 2014). "Kailash Satyarthi loves to cook for rescued child labourers". news.biharprabha.com. IANS. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Rathi, Nandini (7 February 2017). "Kailash Satyarthi's Nobel Prize citation stolen, but his is not the first". The Indian Express. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023.

- ^ "India activist Kailash Satyarthi's stolen Nobel medal recovered". BBC News. 12 February 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ "Bachpan Bachao Andolan produced film nominated for New York Film Festival". globalmarch.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Anjali Bisaria (7 September 2017). "11 Human Rights Activists Whose Life Mission Is to Provide Others with A Dignified Life". Indiatimes.com.

- ^ "Fellows: Kailash Satyarthi". Ashoka: Innovators for the Public. 1993. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ "Nobel Peace Prize 2014: Pakistani Malala Yousafzay, Indian Kailash Satyarthi Honored For Fighting For Access To Education". Omaha Sun Times. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Aachener Friedenspreis 1994: Kailash Satyarthi (Indien), SACCS (Südasien) und Emmaus-Gemeinschaft (Köln)". Aachener Friedenspreis. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014.

- ^ Ben Klein. "Trumpeter Awards winners". National Consumers League.

- ^ "Robert F Kennedy Center Laureates". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Our Board". 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Human Rights Award of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung". fes.de. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ "Medal Recipients – Wallenberg Legacy, University of Michigan". Univ. of Michigan. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ "Kailash Satyarthi – Architect of Peace". ArchitectsOfPeace.org.

- ^ "Heroes Acting To End Modern-Day Slavery". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ "Kailash Satyarthi". Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Kailash Satyarthi". globalmarch.org. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Social Activist Kailash Satyarthi to get 2009 Defender of Democracy Award in U.S." 20 October 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ P.J. George (10 October 2014). "Malala, Kailash Satyarthi win Nobel Peace Prize". The Hindu.

- ^ "The Alliance University conferred 2014 Nobel Laureate Mr. Kailash Satyarthi and Padma Bhushan SMT. Rajashree Birla the Honorary Doctor of Philosophy degree".

- ^ "Satyarthi's '3D' model: Dream, discover, do". Times of India. 21 February 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ "Nobel-winner Kailash Satyarthi is now Harvard's 'Humanitarian of the Year' | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. 17 October 2015.

- ^ IANS (23 April 2017). "Satyarthi given P.C. Chandra award". Business Standard India – via Business Standard.

- ^ "Nobel Peace laureate Kailash Satyarthi felicitated with Lifetime Achievement Award". India TV. PTI. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Mother Teresa award to activists, NGOs that fight forced labour and human trafficking". Asia News. PTI. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

External links

edit- Official website

- Kailash Satyarthi at TED

- "How to make peace? Get angry" (TED2015)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Kailash Satyarthi on Nobelprize.org