This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2013) |

Dudley Flats was a locality in Melbourne, Australia, in the 1920s–1950s, which supported a homeless camp during the Great Depression.[1]

| Dudley Flats Melbourne, Victoria | |

|---|---|

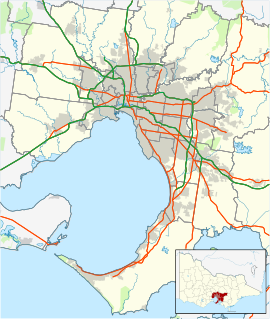

| Coordinates | 37°48′40″S 144°55′59″E / 37.811°S 144.933°E |

| Postcode(s) | 3003 |

| Location | 3 km (2 mi) from Melbourne |

| LGA(s) | City of Melbourne |

Location edit

It was located near the Melbourne docks beyond Dudley Street, south of Footscray Road, and on either side of the Moonee Ponds Creek. The area was formerly part of Batmans Swamp, a large saltwater lagoon, which by the mid 19th century had become fouled with effluent from the growing city.[2]

Dudley Flats was on the fringe of the Melbourne city area, and became a dumping ground, with rubbish tips and a destructor established in the 1860s by the Melbourne City Council and Victorian Railways. The Melbourne Harbour Trust deposited dredged silt as part of land reclamation, and the railways tipped ash from locomotives at the North Melbourne Locomotive Depot from around 1888.[2]

History edit

During the Great Depression of the 1930s (and also possibly from an earlier date), the site was visited and then occupied by Melbourne's poor and homeless who scavenged for scrap and rags from the tips, and built humpies out of discarded rubbish such as old timber and corrugated iron, even lino and hessian sacking. By 1935, over 60 humpies had been erected along the waterways and around the rubbish tips.[2]

Despite regular raids by the police and possibly Harbour Trust officers, who attempted to move people out and demolish their huts, the area continued to be occupied at least up until World War II. The camps had been able to remain or be reestablished in part because of disputes between the various government bodies over who had authority, with the Railways Department, Melbourne City Council, the Melbourne Harbour Trust, the Board of Works, and the Lands Department, all refusing to claim responsibility for the area. Some of the residents were unemployed or underemployed labourers who occasionally gained work with shipping agents and stevedores at times of peak demands, but were otherwise left to scavenge an existence as best they could.

The social reformer Frederick Oswald Barnett made several inspections of the congested residential areas of Melbourne's inner suburbs in 1933, including Dudley Mansions as the humpies were called.[3] He photographed the slums and the residents' living conditions and recorded information on the residents' state of health, income, and where they obtained work (if at all).

This material contributed to reports on slum conditions which eventually pressured the government into passing the Housing Act of 1937.[4]

Structure of the camps edit

There were several separate camps in the area identified by Bamett and Edgar Thomas Wood, the Melbourne City Council health inspector from 1910 to 1949.[5] Dudley Flats proper was located south of Footscray Road on the banks of the Coal Canal – constructed in the 1880s as an outlet for Moonee Ponds Creek, and to allow barges to unload coal at the locomotive depot. The 'Batchelor Quarters' were located on the north side of Dudley Street near a bridge over the canal, while 'Happy Valley' was on the east side of the canal. Residents were given notice of eviction in 1938,[6] but nothing seems to have been done to remove them. The Melbourne City Council hosted a conference of the authorities responsible, which resolved unanimously: that the shacks and their occupants on areas of land at West Melbourne controlled by the Lands Department, Harbour Trust and Railways Dept, constitute a nuisance and should, in the occupants' interests, the interests of the community, and for health reasons, be removed therefrom ... the Conference recommends that the Departments concerned be asked to give the occupants notice to vacate the area within one month, and, on vacation, to have the structures entirely demolished.[7] A little later council resolved to instruct the town clerk (Mr. H. S. Wootton) to discuss the matter with the Lands Department with a view ... to serve notices to quit on the Inhabitants, and to house them in charitable homes.[8]

According to Council files, the settlement was abandoned in the early 1940s, because the nearby tips no longer held a living for scavengers after waste recovery schemes had been initiated to assist in the war effort.[2][9]

Official settlement in the area seems to have involved only the occasional watchman at the nearby wharves. For example, Clement F. Harvey is recorded as living beside the Railway Canal on the North Side of Dudley Street West Melbourne in the Sands and McDougall Post Office Directory for 1929. However, the unofficial, and possibly illegal occupation of Dudley Flats was not recorded in the normal official sources.

Jack Peacock, a salvage dealer, was popularly known as the 'King of Dudley Flats' and was the flats' longest resident, having arrived in about 1932 and remained until the early 1950s, insisting on his rights to remain, claiming he had money enough to support himself and This life suits me and it is only the mental weaklings who desire to remove me. Men of education would allow me to remain."[7][10]

Later history edit

In 1987, 60 demonstrators constructed a shanty town near Footscray Road to protest the lack of public housing.[11]

Archaeological excavations in 1999 for the City Link Freeway exposed thousands of bottles and other rubbish from the tips, but it was not possible to distinguish remains of the settlement (which was built of tip rubbish on top of tip rubbish and eventually buried in tip rubbish).[2]

Depictions in art and literature edit

Dudley Flats was a popular subject for painters from the late nineteenth century to about 1950, possibly in part because of the picturesque qualities created by wasteland and fringe settlements. These works included:

- McCubbin, Frederick (1855-1917): Dudley Flats, West of Melbourne c1880s Oil on canvas, 25.5 x 36 cm, signed lower right F. McCubbin. Label attached verso, 25 x 35 cm; Dudley Flats, West of Melbourne[12]

- Sandford, A: Dudley Flats to Port Melbourne. 1930 oil painting[13]

- Fullbrook, Samuel Sydney (Sam). 1922-2004:[14]

- Dudley Flats, Australian Watercolour on paper, signed and dated '47 lower right, 33.5 x 42.5 cm;

- Figures in a Landscape, Dudley Flat, 1946 oil on canvas 61.0 x 65.0 cm;

- Dudley Flats, West Kensington, Melbourne Oil on canvas, signed with initials 'S. F, lower right, 40 x 49.5 cm;

- Dudley Flats 1947 Watercolour, signed 'Fullbrook' and dated '47 lower right, 33.5 x 42 cm

- Dudley Flats, West Kensington, Oil on canvas, signed 'S. F.' and dated '48, 39.5 x 49.5 cm;

- Dudley Flats, West Kensington Oil on canvas, signed with initials and dated 49 [?] lower right, 40 x 49.5 cm;

- Dudley Flats, West Kensington, Melbourne Oil on canvas, initialled and dated lower right, 'S. F. 49', 39 x 48 cm;

- Dudley Flats, West Kensington Signed lower left, 39.2 x 49.5 cm;

- Dudley Flats, West Kensington, Melbourne Oil on canvas, signed with initials lower right, 40 x 49.5 cm.

- Crossley, George S. Dudley Flats, Watercolour, signed 'G. C. Crossley', lower left, 27.5 x 40 cm[15]

- Hunter, William, Melbourne from the Dudley Flats, Watercolour, signed lower right, 18 x 33 cm[16]

- Harding, Arthur William (Bill). Dudley Flats, Oil on board, signed lower right, 50 x 60 cm[17]

Reference in literature or quotes from literary figures relating to Dudley Flats are also common in the second half of the twentieth century:

- Barry Jones identified a visit to Dudley Flats with his mother as a major event that influenced him profoundly as a child. He ... had a sense, a moral sense, but also an aesthetic sense, to say, "People shouldn't be living like this."'[18][19]

- "My Brother Jack" by George Johnston mentions: There were quite a few 'metho' drinkers living around Dudley Flats at that time.

- Barry Humphreys recounted how Dudley Flats was known to everyone, but was not a place where well-bred people would go.[20]

In 2006, Sharon Thorn completed a PhD thesis on the artistic possibilities in fringe life.[21]

In 2018, Griffin Press (Scribe Publications) launched a combined social history, psychogeographic contemplation and biography of three specific residents of the Dudley Flats shanty town, Blue Lake, researched and written by David Sornig.

References edit

- ^ John Lack, 'West Melbourne Swamp' eMelbourne encyclopedia

- ^ a b c d e Gary Vines (1999) Dudley Flats Archaeological Investigation, www.academia.edu

- ^ One of the "Dudley Mansions", The Unsuspected Slums West Melbourne, Culture Victoria.

- ^ Barnett collection of Historic Photographs, Record 544, Housing and Construction Victoria Library. Department of Planning and Housing.

- ^ "Drab Memories of Dudley Flats". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 15 July 1949. p. 2. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ "DUDLEY FLATS DWELLERS". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 30 June 1938. p. 2. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ a b "This Life Suits Me": Dudley Flats to Docklands', Kasia Zygmuntowicz, Public Record Office Victoria, published in Ancestor December 2002.

- ^ "DUDLEY FLATS AGAIN". The Argus. Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 1 March 1939. p. 4. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ Newspaper clippings and Wood report in Melbourne City Council Archives, file 38/1894 on Dudley Flats.

- ^ VPRS 5357 Land Selection and Correspondence Files, unit 4166, item 34, file G 57040 'West Melbourne – Dudley Flats'

- ^ 'Shanty town at Dudley Flats', The Age, 16 March 1987

- ^ Quarterly Fine Art Auction, Platinum House by Lawson~Menzies, February 13, 2013, Kensington, Australia

- ^ A treasury of Australian art from the David Levine Collection. Adelaide, Rigby, 1981

- ^ Selected works, Australian Art Sales Digest.

- ^ Crossley, George S, Australian Art Auction Records

- ^ Hunter, William Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Art Sales Digest

- ^ Harding, Australian Art Sales Digest

- ^ Barry Jones Interview Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, ABC Talking Heads, with PETER THOMPSON, screened: 26/06/2006

- ^ Barry Jones Archived 24 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, The National Interest, 6 August 2000.

- ^ Humphries, Barry. "Return of a Passionate Pilgrim.", The Age, 7 October 2005.

- ^ Sharon Thorne, Making Badlands, Transformations, No. 13, 2006.

Other sources edit

- Barnett, F. Oswald. The Unsuspected Slums, Melbourne, 1933.

- C. P. Billott Melbourne's Missing Chronicles by John Pascoe Fawkner. Quartet Books 1982.

- Footscray's First Hundred Years. Footscray Advertiser 1959.

- R. L. Greenaway, Historical Usage of the Lands ... of the West Melbourne Swamp, Part of Docklands Heritage Study – Report to Docklands Authority.

- J. Lack, Worst Smelbourne: Melbourne's Noxious Trades in Davidson, The Outcasts of Melbourne.

- Melbourne City Council Archives, file 38/1 894 on Dudley Flats.

- Royal Commission of Low Lands South and West of the City of Melbourne (Low Lands Commission) appointed 12 August 1872: Progress Report VPP 3, 62, 1873; Evidence of Hon T. Loader, Government Surveyor.

- Vines, G. Industrial Land and Wetland, Melbourne's Living Museum of the West.

- Ward, Andrew, Milner, Peter & Vines, Gary. Docklands Heritage Study, Department of Planning 1991.