| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Jengod (talk | contribs) 4 months ago. (Update) |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| An editor has marked this as a promising draft and requests that, should it go unedited for six months, G13 deletion be postponed, either by making a dummy/minor edit to the page, or by improving and submitting it for review. Last edited by Jengod (talk | contribs) 4 months ago. (Update) |

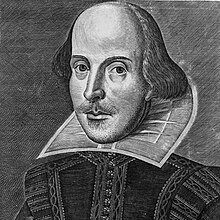

William Shakespeare was believed to have been born in April of 1564 in the town of Stratford, England.[1] He grew up to be one of the most influential writers of all time. Shakespeare wrote almost 40 plays and over 150 sonnets, all of which have been translated into almost every language in the world.[2] They continue to be studied and reinterpreted hundreds of years later. The plays were released for the first time collectively in the infamous First Folio, which was published in 1623.[3] The sonnets were omitted from this work as they had been published in 1609, a few months after the death of his wife Anne Hathaway, under the title Shakespeare's Sonnets.[4] There are not a lot of surviving records of Shakespeare’s personal life, so scholars have had to make assumptions based on his writings, more specifically his sonnets.[5] The lack of discussion on religion in his sonnets and the surprising gender and sexual fluidity present a lot of opportunity to interpret.

In 1563, just one year before the birth of Shakespeare, Elizabeth I reinstated the Buggery Act of 1533, which declared all “deviant” sexual behaviours, including sodomy and bestiality, illegal and punishable by death.[6]

A queer reading of the Fair Youth edit

Shakespeare’s infamous sonnets hold various themes of misogyny, reproduction through gendered binaries and reproduction through poetry. Many scholars hesitate to name these sonnets as queer because in doing so they would be assigning this identity to Shakespeare himself. Moreover, the sonnets are a series pertaining to the Fair Youth and in only reading Sonnet 20 as queer, the meaning of the entire sequence leading up to this is lost. Understanding a queer perspective through history by reading texts through a queer lens offers new insight not only to the texts but how queer life was able to materialize and operate in this time.

Sonnet 5 edit

Sonnet 5 holds fears of time as it continues through the seasons.“For never-resting time leads summer on”(5.5),[7] points to winter overtaking summer and old age overtaking beauty, namely that of the Fair Youth. In poetry, summer is associated with happiness, beauty and the sun and the winter with desolate climate, sadness and death. These motifs lend to the fear that winter(death) will meet the Fair Youth and he will be forgotten by time and by the world. It relates to the aging of the Fair Youth, Shakespeare is concerned with preserving this beauty and fears that the Fair Youth will become old and non-desirable to the world. He deems it unfair that; “Beauty o’ersnow’d and bareness everywhere” (5.8)[7] will be what is left of him. This is reenforced later, “Nor it nor remembrance what it was” (5.12).[7] In later sonnets he develops this theme of sexual reproduction and poetic reproduction. “But flowers distill’d though they with winter meet,/Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet.” (5.13-14)[7] is Shakespeare’s hint that although summer is equated to youth and both will end, the flowers can recreate the essence of the summer. Pointing to the possibility of the beauty of the Fair Youth can be continued through generations in their family and through sexual reproduction, which is explored throughout Sonnet 6.

Sonnet 17 edit

Sonnet 17 contains the theme of poetic reproduction that is present through the sonnets. In earlier sequences, Shakespeare wishes to capture the true beauty of the Fair Youth for generations to come, here he begins an attempt to preserve the Fair Youth through his words, although he fears that he is too beautiful to be fully captured in words. He contrasts the Fair Youth to heavenly and earthly beauty, “This poet lies,/Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces.”(17.7-8),[7] in doing this he may be making a claim that the Fair Youth’s beauty is so grand he cannot possibly be from earth. However, later on in the sonnet he states; “But were some child of yours alive that time,/You should live twice, in it, and in my rhyme.”(17.13-14).[7] This idea continues in Sonnet 20 with the growing fears that poetic reproduction won’t be enough to encapsulate the beauty and he must reproduce a child in his image so that his beauty will live on through time. Judith Kegan Gardiner states; "Underlying the sonnets and generating many of their paradoxes is the impossible syllogism: if men could only marry one another, time would stop."[8]There is a reciprocal fear that the youth will grow old and less desirable over time, so their offspring must live in the image of the youth. It is important to note that the reproduction Shakespeare is pushing the Fair Youth towards, is a life with a wife and children. This leads most scholars to believe that these sonnets are not queer in nature because the Fair Youth is destined to end up in a heteronormative union. However, Kegan Gardiner argues; "In his sonnets as in his plays, Shakespeare assumes that romantic love should initiate heterosexual courtship and be consummated in marriage."[9] Through a queer perspective, a male-male union is not accepted due to sodomy laws and was punishable by death, so if a queer person wanted to survive in this climate they would end up in a heteronormative union.

The Dark Lady and misogyny edit

Sonnet 20 edit

Sonnet 20 presents the Fair Youth as a woman, but better. This sonnet, known for the ambiguity around gender within it, illustrates both the misogynistic and the potentially queer thoughts within Shakespeare. “A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted,”(20.1)[7] describes the Fair Youth as a naturally beautiful woman. This line, while lifting up the Fair Youth to an understood level of beauty, also shames women for their makeup and the way they “paint” their faces. The theme of elevating the Fair Youth by depreciating women and femininity is very present throughout the whole sonnet. It is seen again in the lines “A women’s gentle heart, but not acquainted/With shifting change, as is false women’s fashion:” (20.3-4)[7] He describes the Fair Youth sharing the gentleness typically associated with women but without the fickleness Shakespeare seems to despise. He attacks women’s fashion and how quickly and easily it changes. He praises the Fair Youth for making the good decisions and staying with them. The final couplet, “But since she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure,/Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.”(20.13-14)[7] explicitly states that the Fair Youth should have physical relationships with women, which is explored further in other sonnets. In these lines Shakespeare argues that the Fair Youth should have these relationships with women but should reserve his true love and devotion for Shakespeare himself. Many scholars understand “she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure” to mean that Nature gave the Fair Youth a penis, solidifying the tension between the feminine and masculine present throughout the sonnet.[10] As a whole sonnet 20 could be described as Shakespeare describing the beauty of the Fair Youth through the lens of everything he thinks is wrong with women.

Sonnet 129 edit

Sonnet 129 is dedicated to Shakespeare’s hatred for the lust and sexual desire he experiences. The sonnet is full of desperate and angry language including "murderous,bloody, full of blame,savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust;” (129.3-4)[7] He discusses the unbreakable cycle of lust very explicitly in the line “Had, having, and in quest to have extreme;”(129.10)[7] The lust itself is unbearable. The fall-out of acting on it is shameful and the act itself doesn’t merit all of the complicated feelings it brings. This cycle weighs on him in this sonnet. He is at war with lust and the shame that he seems to feel it inherently brings. These intense feelings are redirected towards women in the final line, “To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.”(129.14)[7] He blames women for this unbearable cycle and in turn redirects all of the negative and aggressive language used in the sonnet towards them. He is both objectifying and vilifying women within this sonnet.[11]

Sonnet 130 edit

Sonnet 130 is a very direct parody of the classic love tropes popularised by Petrarch within his Canzonire. Shakespeare spends the sonnet turning these tropes on their heads.[12] The sonnet seems to be degrading the women he is discussing because of this subversion. However the final couplet expresses the message Shakespeare was attempting to get across.”And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,/as any she belied with false compare.”(130.13-14)[7] He is saying that he loves his mistress(the Dark Lady) as she is and does not need false comparisons to express that. This sweet message is corrupted in the context of other poems, specifically those that discuss the Fair Youth. In these Shakespeare plays into these tropes and takes them even further. Sonnets 17 and 18 and their discussion of reproduction present a very obvious contrast in his feelings toward the Fair Youth and the Dark Lady.

Venus and Adonis and gender ambiguity edit

In Shakespeare's poem Venus and Adonis there are multiple aspects of the portrayals of each character that depicts queerness, specifically through the departure from typical romantic gender roles.[13] One aspect of this is the emphasis on the size difference between Venus and Adonis. While the poem already casts Venus in the position of the pursuer, she is also depicted as larger physically. Adonis is referred to as a ‘boy’, and that is emphasized when it is rhymed with ‘toy’, showing his passivity in their dynamic. Another aspect of the more feminine portrayal of Adonis is the descriptive words Shakespeare uses when discussing him and his beauty, using terms such as “rose-cheeked” which typically carry a more feminine connotation. The reverse is done with Venus, with her openly describing her like a “bold-faced suitor”. These are non-normative gender descriptions, demonstrating Adonis and Venus’ romantic interactions as queer in respect to typical gendered expectations. As much as Venus’ role as the ‘suitor’ or pursuer is a disruption of the typical role of women in romantic interactions, it also emphasises how Adonis subverts expectations. Adonis in this poem is frequently depicted as uninterested in Venus, which is another aspect of his non-normative role in the romantic dynamic. [14]

Sonnet 53 edit

Sonnet 53 is discussed through queer themes as the description of a singular beauty is demonstrated through both a feminine and a masculine figure, those being Adonis and Helen of Troy. This mention of Adonis as the male epitome of beauty also connects to Shakespeare's poem Venus and Adonis, taking a more androgynous approach to describing beauty. As is done in Sonnet 20, Shakespeare uses the epitome of masculinity and femininity in the same description of physician beauty, which leads to a more queer, and less gendered, portrayal of physical beauty. Therefore, as seen in Venus and Adonis and Sonnet 20, the use of feminine language on someone who is understood as a beautiful man leads to a more androgynous and queer representation of beauty.[15] Additionally, Adonis often represents themes of fertility in Greek mythology, once again linking the character to a more feminine representation.[16]

Publication and Interpretation edit

Another important aspect of understanding Shakespeare's sonnets through a queer lens is understanding the tension between Shakespeare as a revolutionary literary figure who pushed creative boundaries, and the impulse to ignore the aspects of queerness and gender non-normativity in Shakespeare’s works to preserve his ‘character’.[17] Up until the 1780’s the main publication of Shakespeare’s sonnets was done by John Benson, who reordered and interfered with many of the sonnets. Benson changed some pronouns from male to female, removing some of the queer themes from the collection. Edmund Malone’s publication of Shakespeare’s sonnets in 1780 changed that, reorganizing the collection in a more authentic way. This was a controversial choice, as there was worry over the dispersions that a more honest collection, that being a more clearly queer collection, would cast on Shakespeare’s character. There was worry of him being seen as queer or as a sodomite, and these fears raised enough moral panic that in 1821 Malone’s collection had notes from John Boswell Jr., mainly focusing on giving information that would discourage a queer interpretation of the sonnets. These notes were clarifications on how “amourous” language was used to describe male-male platonic friendships, and stating that Shakespeare did not have any romantic attachments to the men he wrote of. These notes obviously state that it was both clear to readers that the Shakesperian sonnets were queer, and shows that queerness as something that gave rise to moral panic.

References edit

- ^ Honan, Park (2003). Shakespeare: a life (Reprinted ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-811792-6.

- ^ Craig, Leon Harold (2001). Of Philosophers and Kings: Political Philosophy in Shakespeare's Macbeth and King Lear. University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780802086051.

- ^ Honan, Park (2003). Shakespeare: a life (Reprinted ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-811792-6.

- ^ Honan, Park (2003). Shakespeare: a life (Reprinted ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-19-811792-6.

- ^ Craig, Leon Harold (2001). Of Philosophers and Kings: Political Philosophy in Shakespeare's Macbeth and King Lear. University of Toronto Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780802086051.

- ^ "The Statutes at large, of England and Great Britain: from Magna Carta to the union of the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland. vol. 3". HathiTrust. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Shakespeare, William (1997). "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Shakespeare's Sonnets".

- ^ Gardiner, Judith (1985). "The Marriage of Male Minds in Shakespeare's Sonnets". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 84 (3): 328–347. JSTOR 27709518. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Gardiner, Judith (1985). "The Marriage of Male Minds in Shakespeare's Sonnets". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 84 (3): 328–347. JSTOR 27709518. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Kolin, Philip C. (Fall 1986). "Shakespeare's SONNET 20". Explicator. 45 (1): 10–11. doi:10.1080/00144940.1986.11483950.

- ^ Chang, Hawk (April 2023). "The Silence of Sound: An Acoustic Study of Shakespeare's Sonnet 129". ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews. 36 (2): 183–189. doi:10.1080/0895769X.2021.1930511. S2CID 236362694.

- ^ Strier, Richard (2007). "The Refusal to be Judged in Petrarch and Shakespeare". A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnets: 73–89. doi:10.1002/9780470997017.ch6. ISBN 9781405121552.

- ^ Sasso, Beatrice (2023). "Queer Elements in Renaissance English Poetry". Thesis and Dissertation Padua Archive.

- ^ Billing, Valerie (2017). "The Queer Erotics of Size in Shakespeare's Venus and Adonis". The Free Library.

- ^ Guy-Bray, Stephen (2020). Shakespeare and Queer Representation. Routledge.

- ^ "Adonis, Rebirth, and the Cycle of the Seasons". British Literature Wiki. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Stallybrass, Peter (2000). "Editing as Cultural Formation: The Sexting of Shakespeare's Sonnets". Shakespeare's Sonnets: Critical Essays: 75–86. ISBN 9780815338932.