| Submission declined on 12 April 2023 by Asilvering (talk). This submission reads more like an essay than an encyclopedia article. Submissions should summarise information in secondary, reliable sources and not contain opinions or original research. Please write about the topic from a neutral point of view in an encyclopedic manner. Thank you for your submission, but the subject of this article already exists in Wikipedia. You can find it and improve it at Crusades instead.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

Comment: This topic is better covered at Crusades, or at articles for specific orders, eg Knights Templar. asilvering (talk) 03:23, 12 April 2023 (UTC)

Comment: This topic is better covered at Crusades, or at articles for specific orders, eg Knights Templar. asilvering (talk) 03:23, 12 April 2023 (UTC)

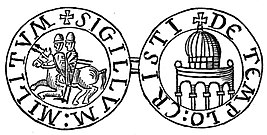

A Crusader was a medieval Christian warrior who participated in a series of military campaigns known as the Crusades. Among the Crusaders there were several military orders including Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller, Knights of the Teutonic Order, etc.[4][5][6][7]

A Crusader was typically a knight, noble, monk or a regular man motivated by religious fervour and rewarded with wealth, land, and honour.[8] Their military organization was led by noble lords and religious leaders, and they often wore distinctive symbols, such as a red cross on their clothing or shields, to signify their commitment to Christianity.[9]

The Crusaders were well known for their distinctive Armor, which included metal helmets, chainmail, and plate armour. They were skilled in a number of combat disciplines, including swordsmanship, archery, and siege warfare, and were renowned for their battle prowess.[10][11]

The Crusaders' identity was based on their religious faith and piety. They believed that their cause was sanctioned by God and that they were defending and spreading Christianity. The Crusaders were often accompanied by priests and other religious figures who provided them with spiritual guidance and performed religious ceremonies, such as mass and confession, on the battlefield.

The Crusaders faced numerous challenges during their campaigns, including harsh weather, long marches, and formidable opponents. They encountered different cultures, languages, and customs in the lands they travelled through, and had to adapt to unfamiliar environments. They also faced political intrigue and conflicts among themselves and with local rulers and factions.

Despite the challenges, the Crusaders were known for their determination and bravery in battle. They fought in several major battles, sieges, and skirmishes during the Crusades, leaving a lasting impact on the history of the Middle Ages. While their efforts did result in short-term gains, including the establishment of Crusader states in the Holy Land, the long-term outcome of the Crusades was complex and multifaceted, with both positive and negative repercussions for both Christian and Muslim societies.[12]

The Crusaders played a significant role in shaping medieval history and are remembered as legendary figures of the Middle Ages. Their story is an important part of the historical narrative of the Crusades, which continues to be studied and debated by scholars and historians.

According to the Cambridge dictionary a Crusader is "a Christian who fought in one of the religious wars of the 11th, 12th, 13th, and 17th centuries, mostly against Muslims in Palestine"

History edit

The first Crusade was launched in 1095 by Pope Urban II, who called for an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem at the Council of Clermont. Thousands of people responded to his appeal, forming a large and diverse army that marched across Europe and Asia Minor.

Motivation edit

Crusaders were motivated by a variety of factors, including religious zeal, a desire for adventure, and the promise of material rewards. Pope Urban II, who proclaimed the First Crusade in 1095, promised crusaders a remission of their sins and a place in heaven if they died fighting for the faith. Many crusaders were also motivated by a desire to liberate the Holy Land from Muslim rule and to protect Christian pilgrims. Others were attracted by the promise of land and riches in the conquered territories.

History edit

While the Crusaders are commonly associated with the campaigns in the Levant, their origins can be traced to the Iberian Peninsula, where Christian forces waged a Holy War against Muslim rulers. This conflict, known as the Reconquista, had a significant impact on the development of early Crusader armies.

The catalyst for the Crusader movement in Spain can be traced back to 1063 when King Ramiro I of Aragon was assassinated by a Muslim at Grados. This event sent shockwaves across Europe and captured the attention of Christian leaders. Pope Alexander II, in response, issued an indulgence – a spiritual reward – to all those who would take up arms and fight for the Cross in Spain. The Papacy's involvement in this early Crusade was pivotal, setting the precedent for papal influence in subsequent Crusades.

To gather the necessary military force, Pope Alexander II appointed a Norman soldier, William of Montreuil, to recruit troops from northern Italy. Additionally, Count Ebles I of Roucy in northern France assembled an army to join the cause. However, the most substantial contingent was brought by Guy-Geoffrey, the Count of Aquitaine, who was entrusted with the command of the expedition.

The initial campaign, despite the collective efforts, yielded limited success. While the town of Barbastro was briefly captured, it was soon lost again. Nevertheless, this early struggle laid the groundwork for the further involvement of European powers in the Iberian Peninsula.

One significant turning point came in 1073, when Count Ebles of Roucy organized a new expedition, and Pope Gregory VII invited Christian princes to participate. Pope Gregory VII also declared that Christian knights could enjoy the lands they conquered from the infidels, providing a powerful incentive for their involvement. This marked a crucial shift, as it introduced the idea of territorial gains and property rights in a Holy War, which would later become a defining characteristic of the Crusades.

In 1078, Hugh I, Duke of Burgundy, led an army to support his brother-in-law, Alfonso VI of Castile, thus contributing to the Crusader forces. In 1080, Pope Gregory VII personally encouraged an expedition led by Guy-Geoffrey, further reinforcing the cause.

The pinnacle of early Crusader success in Spain was the capture of Toledo in 1085 by the Castilians. This victory symbolized the potential of Christian forces against the Muslim rulers. However, this triumph was followed by a revival of Muslim resistance, led by the Almoravids, which posed a new and formidable challenge.

Starting from 1087, Christian knights were urgently summoned to Spain to counter the Almoravids, underscoring the ongoing need for reinforcements. This prolonged conflict in Spain served as a continuous source of inspiration for the broader Crusader movement, ensuring that the call to arms remained relevant and compelling.[13]

Pope Urban II, a subsequent Pope, lent his support to the cause and called for assistance, emphasizing the continued involvement of the Papacy in the war against the infidels in Spain. The Spanish Crusade, with its shifting tides of victory and defeat, effectively paved the way for the later and more famous Crusades in the Holy Land.[14]

References edit

- ^ Archer, Thomas Andrew; Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge (1894). The Crusades: The Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. T. Fisher Unwin. p. 176.; Burgtorf, Jochen (2008). The central convent of Hospitallers and Templars : history, organization, and personnel (1099/1120–1310). Leiden: Brill. pp. 545–46. ISBN 978-90-04-16660-8.

- ^ Burman 1990, p. 45.

- ^ Barber 1992, pp. 314–26

By Molay's time the Grand Master was presiding over at least 970 houses, including commanderies and castles in the east and west, serviced by a membership which is unlikely to have been less than 7,000, excluding employees and dependents, who must have been seven or eight times that number.

- ^ Jones, Dan (2019-09-05). Crusaders: An Epic History of the Wars for the Holy Lands. Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1-78185-887-5.

- ^ Kedar, Benjamin Z. (2022-03-30). Crusaders and Franks: Studies in the History of the Crusades and the Frankish Levant. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-94705-3.

- ^ Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 2–8. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- ^ "Crusader | English meaning". Cambridge Dictionary.

- ^ "What were the different motives for the Crusades? - The Crusades - KS3 History Revision". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ Nicholson, Helen J. (2004). The Crusades. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32685-1.

- ^ Jones, Dan (2017-09-19). The Templars: The Rise and Spectacular Fall of God's Holy Warriors. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-698-18643-9.

- ^ Nicholson, Helen J. (2004). The Crusades. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-313-32685-1.

- ^ Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2011). The Crusades, Christianity, and Islam. Columbia University Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-0-231-14625-8.

- ^ France, John (1994). Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-58987-1.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1951). A History of the Crusades: Volume 1, The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. CUP Archive. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-521-06161-2.