Dorotea Bocchi (1360–1436) (also sometimes referred to as Dorotea Bucca) was an Italian noblewoman known for studying medicine and philosophy.[1][2] Dorotea was associated with the University of Bologna, though there are differing beliefs regarding the extent of her participation at the university ranging, from whether she taught or held a position there.[1][2][3][4][5] Despite these debates, there is consensus that she flourished and was active at the university for more than 40 years, beginning from 1390 onwards.[2][3][6][7][8][9]

Dorotea and Her Family edit

Dorotea's father, Giovanni di Bocchino Bocchi, was a Professor of Medicine at the University of Bologna.[1][4][5][7] Confirmed through the genealogy chart created by Giovanni Niccolò Pasquali Alidosi, Dorotea was included as one of Giovanni Bocchi’s children.[4] Her mother was Ghisia da Saliceto.[4] The number of her siblings is not easily found, but such sources indicate that she was one of several.

In terms of marriage, Dorotea was married twice.[4] First to Bartolomeo Carlini and then to Giacomo Paltroni.[4]

Father and Daughter Legacy at the University edit

In 1596, Francesco Serdonati, an Italian academic and expertise of grammar, commemorated Giovanni di Bocchino Bocchi for his tenure at the university and simultaneously praised Dorotea for her literacy and oration skills.[4] Serdonati also articulated how both Dorotea and her father made decent profits with their academic pursuits.[4]

In 1620, Francesco Agostino Della Chiesa in the Theatro delle Donne asserted that Dorotea’s teaching experience began in 1419, and librarian Ludovico Maria Montefani Caprara of the Institute of Sciences of Bologna also affirmed that in 1420 Dorotea began to teach philosophy.[4] Such pursuits indicate that Dorotea followed in the footsteps of her father. According to Brooklyn Museum and Scholar Monique Frize, Dorotea took after her father by becoming both a professor of philosophy and medicine.[2][7]

Debates on Dorotea edit

Sedronati stated that Dorotea only studied philosophy.[4] Art Historian Caroline P. Murphy, Historian Leigh Whaley, and Historian Gabriella Berti Logan confirm that Dorotea studied medicine.[1][3][5] Meanwhile, Professor of Engineering and Information Technology Monique Frize affirm that Dorotea studied both.[2] It was common during this time period for the university faculty at Bologna to study in both the discipline of medicine and philosophy.[10]

The Italian historian Tommaso Duranti however doubts the historical existence of Bucca and considers her fictional creation designed to increase the fame of the university and associated families.[11] Among the scholars who affirm and accept Dorotea as a historical figure include: Art Historian Caroline P. Murphy, Historian Leigh Whaley, Historian Gabriella Berti Logan, and Dr. Monique Frize.[1][3][5]

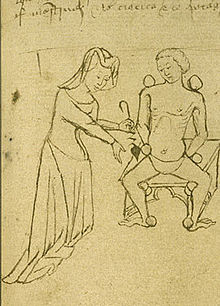

Notable Artwork on Dorotea edit

In 1606, Pablo de Ribera, a Lateran canon, included Dorotea in a cohort of portraits titled Le Glorie Immortali to depict exceptional women.[4] Between the time period of 1680 and 1690, a sculptor from Casa Fibbia included Dorotea in a cohort of Bolognese women, which provides a plausible image of Dorotea's appearance.[12]

Comparisons and Connections to Other Historical Women edit

Before the 19th century, Italy was notorious for having a more open liberal attitude towards educating women in medical fields compared to England. Examples of the active participation and contribution of Italian women in Italy includes Anna Morandi Manzolini, a former Professor of Anatomy at the University of Bologna in 1760,[8] Trotula of Salerno (11th century), Abella, Jacobina Félicie, Alessandra Giliani, Rebecca de Guarna, Margarita, Mercuriade (14th century), Constance Calenda, Calrice di Durisio (15th century), Constanza, Maria Incarnata and Thomasia de Mattio.[13]

In the context of Dorotea, while some attribute Dorotea as the first woman to be a university teacher at the University of Bologna and as a predecessor of other notable women at the university, other scholars believe the first to hold this title was Laura Bassi.[9][3][5][14][15]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e Murphy, Caroline P. (1999). "In praise of the ladies of Bologna?: the image and identity of the sixteenth-century Bolognese female patriciate". Renaissance Studies. 13 (4): 440–454. doi:10.1111/j.1477-4658.1999.tb00090.x. ISSN 0269-1213. PMID 22106487. S2CID 35152874.

- ^ a b c d e Frize, Monique (2013), "Women in Science and Medicine in Europe Prior to the Eighteenth Century", Laura Bassi and Science in 18th Century Europe, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 25–37, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-38685-5_3, ISBN 978-3-642-38684-8, retrieved 2021-11-21

- ^ a b c d e Whaley, Leigh (2016-09-01). "Networks, Patronage and Women of Science during the Italian Enlightenment". Early Modern Women. 11 (1): 187–196. doi:10.1353/emw.2016.0052. ISSN 1933-0065. S2CID 164548638.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tommaso Duranti, Dorotea Bocchi. Di donne, università medievali e internet, "Storicamente", 15-16 (2019-2020), no. 55. DOI: 10.12977/stor801

- ^ a b c d e Logan, Gabriella Berti (2003). "Women and the Practice and Teaching of Medicine in Bologna in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 77 (3): 506–535. doi:10.1353/bhm.2003.0124. ISSN 1086-3176. PMID 14523259. S2CID 23807446.

- ^ Edwards JS (2002) A Woman Is Wise: The Influence of Civic and Christian Humanism on the Education of Women in Northern Italy and England during the Renaissance. Ex Post Facto Vol. XI Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 19 January 2007)

- ^ a b c Brooklyn Museum: Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Heritage Floor: Dorotea Bucca (accessed 22 August 2007)

- ^ a b Jex-Blake S (1873) 'The medical education of women', republished in The Education Papers: Women's Quest for Equality, 1850–1912 (Spender D, ed) p. 270 (accessed 22 August 2007)

- ^ a b Frize, Monique. Laura Bassi and Science in 18th Century Europe: The Extraordinary Life and Role of Italy’s Pioneering Female Professor. New York, NY: Springer, 2013.

- ^ Duranti, Tommaso (2017). "Il collegio dei dottori di medicina di Bologna: università, professioni e ruolo sociale in un organismo oligarchico della fine del medioevo". Annali di Storia delle Università Italiane. 21: 151–177 – via www.jstor.org.

- ^ Tommaso Duranti, Dorotea Bocchi. Di donne, università medievali e internet, "Storicamente", 15-16 (2019-2020), no. 55. DOI: 10.12977/stor801

- ^ "Busto di dama bolognese illustre - Dorotea Bocchi - Collezioni - opere d'arte, quadri, dipinti, sculture, collezioni pubbliche e private a Bologna - GENUS BONONIAE". collezioni.genusbononiae.it. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ Walsh JJ. 'Medieval Women Physicians' in Old Time Makers of Medicine: The Story of the Students and Teachers of the Sciences Related to Medicine During the Middle Ages, ch. 8, (Fordham University Press; 1911)

- ^ Barone, Arturo. The Italian Achievement: An A-Z of Over 1000 'firsts' Achieved by Italians in Almost Every Aspect of Life Over the Last 1000 Years, ed. Renaissance 2007, p. 141

- ^ Monique., Frize (2009). The bold and the brave : a history of women in science and engineering. University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 978-0-7766-0725-2. OCLC 696022285.